Educate youths about our history

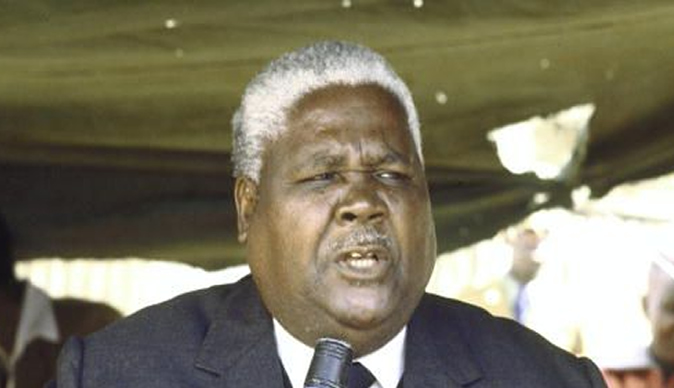

Opinion Saul Gwakuba Ndlovu

QUESTIONS have been asked by predominantly people who grew up in Zimbabwe after it became independent about why thousands of this country’s black people had to fight for Zimbabwe’s freedom.Some of those post-independence Zimbabweans now live in relative comfort in the low density suburbs of the country’s urban centres.

Some live in medium density areas, some reside in high density suburbs and others in the communal areas, formerly called native reserves. Yet others are engaged in commercial farming or in mining areas where only white people were allowed to run businesses or live during the Rhodesian era.

These people cannot imagine how oppressed and disadvantaged black people were in this country — their own land.

As the nation celebrated its 34th Independence anniversary yesterday, it is important for those who experienced the hardships and humiliation of the black people by the white settlers to educate the post-independence generation about the country’s immediate past.

When Cecil John Rhodes sent his Pioneer Column to Mashonaland in 1890, he was the Prime Minister of the Cape Colony, where he later passed a law called the Glen Grey Act.

That law was named after the Glen Grey District east of Queenstown and west of the Indwe River. It was made a part of Cape Colony after the eighth frontier war in 1852 and was meant for the Tembu people, Nelson Mandela’s tribe, the area was mostly densely populated.

The law was introduced to the Cape Colony parliament on July 27, 1894 by Rhodes himself, in his capacity as Minister for Native Affairs. That law created the first native reserve in Southern Africa and Rhodes called it the “Native Bill for Africa” the day he introduced it to the House.

It was passed in August 1894 under the name “Glen Grey Act”. Its aim was, so declared Rhodes in no uncertain terms, to force more kaffirs into the wage- labour market, by first limiting the land available to them on the native reserves and second by imposing a ten shilling labour tax on all those who could not prove that they had been in bona fide wage employment for at least three months in a year.

That law was introduced by the British South African Chartered Company to create the first native reserves in Southern Rhodesia in 1894, about a year after the British-Ndebele 1893 war that forced King Lobengula into exile across the Zambezi River.

In 1930, some seven years after the country had been granted what was called internal self-government, the Southern Rhodesia Parliament passed a law called the Land Apportionment Act.

That law was based if not in word but actually in spirit on the Glen Grey Act.

It divided the country almost equally between the black people (who were the overwhelming majority) and the white settlers a tiny percentage of the country’s population.

The government then forcefully removed whole black communities from regions ear-marked for the white settlers to low-lying areas where malaria is endemic. The country is, incidentally, divided according to altitude into three regions, the high veld, the middle veld and the lowveld.

The high veld is the healthiest, followed by the middle veld and the low veld is the worst place for human habitation, and that was where the Southern Rhodesian government dumped large numbers of blacks who were moved by force of arms from the healthy regions to make room for white settlers.

In the urban areas, the government created generally areas for its racial group. White suburbs on the northern, eastern and southern sides of the towns and cities, the areas meant for Indians and coloureds were generally much nearer to the towns or cities, virtually contiguous to the industrial sites.

Those for the black people were sited to the western side of the industrial areas. The wind in this part of the African continent is usually from the east to the west, so the industrial smog was blown to the black people’s residential areas known as locations or townships or compounds.

Not only that, municipal councils administering various urban centres provided some of the worst type of accommodation for their black residents. The Salisbury (now Harare) City Council and the Gatooma Town Council put up what were called nissen huts in parts of Harare and Rimuka locations respectively. Nissen huts were made of corrugated iron sheets and each hut was meant to accommodate up to 10 male workers.

In Gatooma (now Kadoma) the black people called those nissen huts “mabugger rooms”

The country’s urban housing projects were the responsibility of the council which operated within the two of the many racially discriminatory laws. The Land Apportionment Act and the Native (urban areas) Accommodation and Registration Act (1946).

Earlier the BSAC used what was known as the Masters and Servants Act to control black workers of whatever category. That law was a carbon copy of a Cape Colony Act of the same name.

It describes every black worker as a servant and not as an employee and strictly controlled their conditions of service and their wages, place of domicile and right of associations.

Meanwhile, out in the native reserves, the black people were running short of land and were flocking to urban, mining centres and commercial farming areas to seek employment.

That was exactly what Rhodes wanted when he crafted the Glen Grey Act in 1894, the law that was the guideline of the Land Apportionment Act.

Native reserves were nominally under traditional (hereditary) chiefs. Some of these chiefs or their immediate predecessors had actively taken part in armed resistance activities against the white settlers but had been subdued because of the technological inferiority of their weapons: their spears, bows and arrows, battle axes and knobkerries versus the white men’s Martin-Henry rifles and the sten gun, tear gas and dynamite.

To control and humiliate those traditional leaders, the white minority settler parliament passed a law in 1928 called The Native Affairs Act, a section of which made it a crime for an indigenous black person to criticise a chief.

The chiefs were placed under a Ministry of Home Affairs section called “the Native Affairs Department”.

They were paid a monthly stipend. For one to be a chief, one had to be approved by the Native Affairs Department, the head of which in each of the country’s 56 districts was a white officer called a native commissioner who was answerable to the Home Affairs Minister.

The country’s traditional leaders (chiefs) were turned into the settler white minority government’s agents by that law. They could no longer raise their voices against the white oppressor, so much unlike Chief Mapondera who died fighting tooth and nail for the freedom of the black people, or like chief commander Mtshana Khumalo whose regiment stood firm on the banks of the Shangani River against the Allan Wilson patrol, and wiped those pursuers of King Lobengula to a man.

The era and role of traditional leaders (chiefs) as fighters for or defenders of the African people against white oppressors and dispossessors were gone.

The successors to that era and their role in this country were leaders of an emerging black working class.

Headed by the charismatic Sergeant Masotsha Ndlovu, the trade union team compromised Charles Mzingeli (Nkomo) and Job M Dumbutshena in Gatooma and Mzingeli in Salisbury. These were men of steel, courage and commitment but low education. They carried the black people’s voice high right up to the late 1940s when the black trade union movement’s leadership was taken over by better educated younger men, Grey Mabhalane Bango, Reuben Jamela, Jason “Ziyaphapha” Moyo, Benjamin Madlela, George Nyandoro, Joseph Msika and Joshua Nkomo.

That was a new revolutionary age in which the colonial power, Britain, would be confronted by those young, well educated, courageous black leaders. It was also because the entire world was no longer what it was in the 1880s when the Berlin Conference (1884-85) attended by colonial powers that decided to divide the African continent among themselves.

African and Asian leaders put their heads together and resolved that enough was enough as far as colonialism was concerned. Coming to the aid of these African freedom fighters were the Asian and the European socialist states at the head of which were the Soviet Union and all the former Camecon countries (Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia and the German Democratic Republic), with all the People’s Republic of China effectively representing the Asian continent.

The African continent for its part came together in 1963 by forming the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) one of whose arms, the Liberation Committee, would provide liberation movements with the material support necessary for armed struggles in their respective areas.

So in Zimbabwe two liberation movements had emerged by 1964: Zapu and Zanu. It was these two revolutionary liberation movements with the material aid by the African Liberation Committee based in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, that prosecuted the armed liberation struggle until a free Zimbabwe was born on April 18, 1980, 34 years ago. The pioneering freedom fighters were selfless, fearless men and women whose commitment to the dignity of the African people was irreversible.

Charting the way against massive odds were such heroes as George “Bonzo” Nyandoro, Joshua Mqabuko Nkomo, Jason “Ziyaphapha” Moyo, Clement Muchachi, Daniel Madzimbamuto, Benjamin Madlela, Sikhwili Kohli Moyo, Robert Gabriel Mugabe, Tarcissius George Silundika, Willie Dzawanda Musarurwa, Edgar ‘Twoboy’ Tekere, Enos Nkala, Morton Malianga, Washington Mahlangu, Leopold Takawira, Samuel Munodawafa, Mark Nziramasanga, Dr Samuel Tichafa Parirenyatwa, Tobias Bolylocke Manyonga, Chief Munhuwepayi Mangwende, William Takavarasha, Michael Mawema, William Mukarati, Francis Nehwati, Edward Silonda Ndlovu, Ackim Matthew Ndlovu, Dumiso Dabengwa, Amos Dzindowangu Ngwenya, Thomas Ngwenya, Paul Mushonga, Eddison Sithole, Stephen Vuma, Rugare Gumbo, Ethan Dube, Welshman Mabhena, Norman Mabhena, Isaac Mswelaboya Sibanda, Todd Msongelwa, Machipisa Joseph, Boyce Mguni, William Mpotyi Sivako, Taffy Moyo, William Ngono, Daniel Yenye Ngwenya and Peter Thebe Juma .

A number of women also played a leading role in the very initial stages of the struggle. Prominent among them were Jane Lungile Ngwenya, Ruth Chinamano and Thenjiwe Lesabe. This list is by no means exhaustive.

Thousands more people joined the armed liberation struggle as it gained momentum right up to the time of the 1979 Lancaster House Constitutional Conference in London when the British Government agreed to hand over the government of its colony of Southern Rhodesia back to the indigenous majority.

The sovereignty of Zimbabwe means that the country belongs to each and every bona fide citizen of Zimbabwe. We live in Zimbabwe as of right and not by sufferance. Whereas we may live in whatever foreign country if we are given a visa to do so, in Zimbabwe we live by right of being Zimbabweans. That is why we should show practical pride in our country’s independence; that is in addition to the fact that it was born of hundreds of thousands of lives of heroes and heroines who paid the ultimate price for its freedom.

Saul Gwakuba Ndlovu is a former freedom fighter and retired journalist based in Bulawayo and he can be contacted on cell 0734328136 or through email: [email protected]

Comments