Efforts to reform UN Security Council progressing slowly

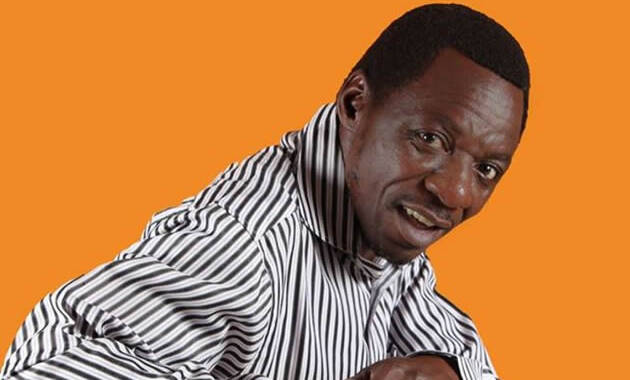

Mabasa Sasa at the United Nations

Mabasa Sasa at the United Nations

Efforts to reform the United Nations Security Council and revitalise the General Assembly are inching along, with Zimbabwe quietly confident that much can be achieved through available mechanisms.

Though Africa’s efforts to make the Security Council more democratic face resistance at various levels, a number of changes could be made without necessarily amending the UN Charter or seeking ratification from the council itself.

The issues are up for discussion at the 70th Session of the General Assembly, which President Robert Mugabe is attending.

President Mugabe is in New York with First Lady Grace Mugabe, ministers Simbarashe Mumbengegwi (Foreign Affairs) and Dr David Parirenyatwa (Health and Child Care), among other senior government officials.

President Mugabe, who is also the African Union Chair, is a firm advocate of a more representative Security Council and robust General Assembly, stating his position — which dovetails with Africa’s common position — at various fora over the years.

Officials told our Harare Bureau that Zimbabwe was fairly confident that the reform agenda could score quick goals because “most of the proposals do not require Charter amendments or Security Council ratification”.

Intergovernmental negotiations on equitable representation on and an increase in the membership of the Security Council, and other matters related to the council, as well as revitalisation of the General Assembly, have been ongoing throughout the year.

The President of the 69th Session of the General Assembly Sam Kutesa, appointed Ambassador Courtenay Rattray of Jamaica to chair the intergovernmental negotiations on Security Council reform with the mandate to shift from the “sterile and monotonous practice of reading statements repeating known positions”, and instead energise the process and take it forward.

To this end, Ambassador Rattray circulated a framework document (62/557) dealing with (1) Categories of membership to the Security Council, (2) Veto power, (3) Regional representation, (4) Size of an enlarged Security Council and its working methods, and (5) Relationship between the Security Council and General Assembly.

The Committee of 10 representing Africa, stuck by the Ezulwini Consensus that Africa should have two permanent members on the Security Council with veto power (if it is agreed that veto power should indeed be retained), and five non-permanent, rotating seats.

The five, veto-wielding permanent members of the Security Council are Britain, China, France, Russia and the United States.

China is hesitant to adopt reforms because Japan, as a member of a group called the G4 also comprising Brazil, Germany and India, wants a permanent seat when Beijing feels Tokyo has not yet shown remorse for the atrocities it committed in World War II.

The United States, like Russia, is generally opposed to a large Security Council, saying the institution could become even more unwieldy and unresponsive to global needs.

Russia, in addition to saying total membership should not surpass 23, also wants Africa to name its two preferred permanent candidates before it can fully support any such reforms.

Africa, on the other hand, maintains that it cannot name any countries until the principle of first awarding it the two permanent seats is satisfied.

The Eastern European bloc wants four more non-permanent seats with one each going to themselves, Africa, Latin America and Asia.

The bloc adds that the Security Council should be expanded by six with Africa getting two permanent seats; and that the issue of whether or not to retain veto power for anyone be revisited after 15 years.

On the General Assembly, the common position of the developing world is that this organ has a greater say in the appointment of a secretary-general.

At present, the Security Council recommends a single candidate and the General Assembly more or less simply rubber stamps it as the former can veto any decision contrary to theirs. This could require amendments to the Charter, something the Russians say should not be done as the General Assembly can be revitalised by revisiting working methods and weeding out outdated and obscure resolutions, and streamlining the agenda while spreading high-level meetings across the duration of the year instead of trying to compress them into the traditional three-week period.

Developing countries insist that the secretary-general must have greater autonomy from the Security Council, and this can be achieved by giving him/her a longer but non-renewable single term.

They also demand structured stocktaking of General Assembly decisions to ensure that they are implemented as agreed.

Comments