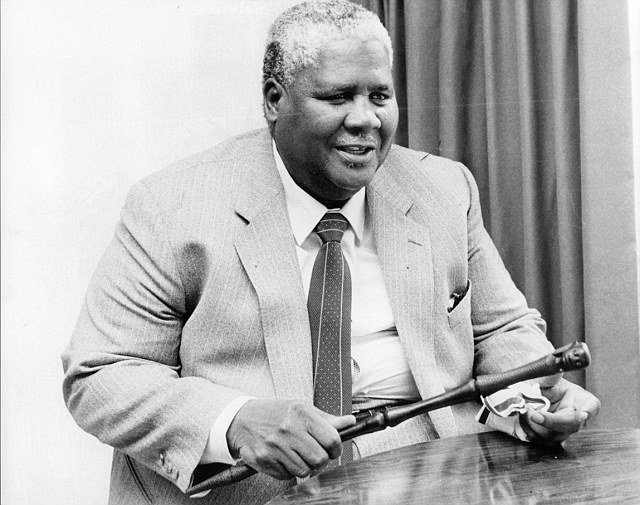

Joshua Nkomo’s road to Uhuru

Yoliswa Dube, Features Reporter

IN pursuit of Zimbabwe’s independence, the late Vice President Dr Joshua Nkomo received a proposed parliamentary structure which was a highly complex one with provisions for 50 ‘A’ Roll and ‘B’ Roll seats, together with a cross-voting system which would leave each roll to have a 25 percent influence on the other.

There was an immediate adverse reaction to the agreement. Dr Nkomo, although stoutly defending his action and that of his fellow-delegates, soon came to realise the strength of the opposition.

He further found his stance weakened by the arrival of a telegram from Leopold Takawira, in London, in which such phrases as ‘diabolical and disastrous’, ‘treacherous to three million Africans’ and ‘untold suffering’ were allegedly employed.

The following day Dr Nkomo flew to London. After discussions with Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations Duncan Sandys, Cde Takawira and Cde Enoch Dumbutshena, he issued a statement to the press in which he repudiated the constitutional agreement.

In explaining his change of attitude he remarked “a leader is he who expresses the wishes of his followers; no sane leader can disregard the voice of his people and supporters.” Indeed, only great leaders of the calibre of Dr Nkomo could say that.

The year 1961 was a year of growing tension between the National Democratic Party (NDP) and the authorities. After much civil unrest, the party was banned on December 10. Zapu, successor to the NDP, was formed on December 18, 1961, and Dr Nkomo was elected its first president.

Father Zimbabwe was in Lusaka, Zambia when Zapu was banned. He states that after some days of thought he came to the conclusion that the time had passed when anything useful could be achieved by party action within Southern Rhodesia.

Two of his parties had been banned, and their assets confiscated, within a matter of nine months. Any further creations would, he believed, be similarly handled. The answer, he concluded, lay in setting-up a ‘government-in-exile’ which, by freely bringing pressure to bear on the United Nations, the Organisation of African Unity and other sympathetic bodies, would stimulate international action to effect political change at home.

Soon after his return to Southern Rhodesia, he called a meeting of the national executive for early April in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania. By this time he was, he said, convinced that Southern Rhodesia would receive independence as part of a ‘package deal’ to end the Federation for which a break up conference was scheduled to start at the Victoria Falls in June, 1963.

At the same time, Dr Nkomo took steps to consolidate his hold on the masses and re-formed the power structure, creating a large number of new, smaller branches to replace the somewhat unwieldy, over-centralised arrangements which had existed previously.

He remained under restriction for about 10 years, although not always in the same place or in the same conditions.

From 1969, he was permitted three-monthly visits from his wife Mama Mafuyana and his children.

During these ten years he came before the public eye on only three occasions: firstly, when he was flown to Salisbury on October 29, 1965 to discuss the situation with Harold Wilson, the Prime Minister of Britain, during the latter’s pre-Unilateral Declaration of Independence visit to Salisbury.

The second occasion was in November 1968 when he was called to Salisbury to meet George Thompson, the Commonwealth Secretary, and Labour Party MP Maurice Foley, in the course of the further negotiations that followed the talks between British Prime Minister Harold Wilson and Ian Smith, the Rhodesian Prime Minister. His last emergence was on February 10, 1972 when he was interviewed by members of the Pierce Commission.

In some sections of history, Dr Nkomo says that during his long period in restriction he thought deeply of the future course of nationalism. In one respect his attitude, if anything, hardened. On the question of majority rule he became unwilling to accept any compromise.

As he said later: “I would be silly to get anything short of majority rule after suffering all these years”. He maintains that he considered carefully the question of unity.

Towards the end of October 1975 he started a series of meetings with Ian Smith designed to prepare the ground for a full constitutional conference.

On November 9, he presided over a meeting of the National Executive at which outbreaks of violence in townships in Harare and Bulawayo were condemned.

On December 1 he and Ian Smith signed in Harare a ‘Declaration of Intent’ to hold a constitutional conference with the minimum of delay.

In early February 1976 he travelled to London where he had talks with James Callaghan, then Foreign Secretary. On February 27, when the talks had reached what he described as a crucial stage, he met Lord Greenfield, who had been sent out from London to gain firsthand knowledge of the situation.

It was this time that he admitted that the nationalist movement was receiving aid from eastern countries because the “western countries wouldn’t agree to help”.

When the talks with Ian Smith collapsed on March 19, Dr Nkomo said the breakdown had been on “the single fundamental issue of majority rule now”.

It wasn’t too long before independence was attained on April 18, 1980.

Comments