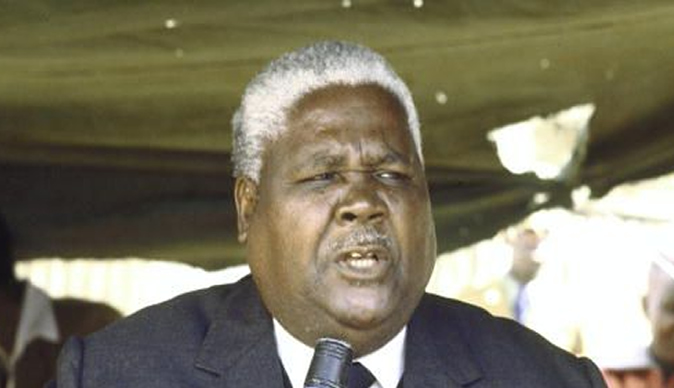

Over to you Cde Deng

IT seems history has once again had its way, repeating itself in so uncanny a way that it is nothing short of astounding.

Of late, historians and experts – obviously spellbound by events that took place in China during the transition from the revered Mao Zedong to Deng Xiaoping, especially just before 1978 – have been drawing parallels at the eerily similar circumstances in Zimbabwe.

In the same way that the former First Lady Grace Mugabe and her ambitious group (G40) tried to gain political power by exploiting the influence wielded by former President Mugabe, China’s “Gang of Four” – which comprised Jiang Qing, the widow of chairman Mao; Zhang Chunqiao; Wang Hongweng and Yao Wenyuan – also tried to play the same card.

However, they all gambled and lost.

The journey to the swearing-in of Cde Emmerson Mnangagwa as President of Zimbabwe has been as tortuous as it was for Deng Xiaoping who was reinstated as a member of the Communist Party of China Central Committee and vice premier in July 1977 after initially being purged by Mao.

Similarly, on Sunday, Cde Mnangagwa was not only reinstated as a member of ZANU-PF Central Committee but was also elected to be the First Secretary of the ruling party.

It does not end there.

By the time Deng assumed the levers of power in March 1978, he was 78-years-old, which is three years older than Cde Mnangagwa.

The rise of Deng smoothed the path for China’s economic miracle, which has seen the transition of the Asian country from an economic backwater to an affluent country within a generation (three decades).

And now that burden rests on Cde Mnangagwa, at least for now.

What is the New Era?

To a large extent, the influence of Marxist-Leninist thought, which arguably became the core of Mugabeism, itself a philosophy to aggressively upend inequalities in whatever form, has significantly shaped ZANU-PF ideological leaning.

The philosophy has remained largely rigid over the years, unable to adapt to a changing world.

It has, in fact, brought Zimbabwe on a collision course with traditional cooperating partners that have a role to play in the development of Zimbabwe.

Again, just like China, which was traumatised by challenges associated with the Cultural Revolution in the decade before 1978, some of the members in ZANU-PF seem to be in the rigid grip of populist thinking.

For example, trying to take over banks under the guise of indigenisation.

But now, with a change of guard, ZANU-PF has a chance to be pragmatic enough to chart a new way forward.

And this is exactly what Deng Xiaoping set out to do to make the country ready for economic prosperity.

But the groundwork had already been laid by Chairman Mao, which is exactly what President Mugabe, as part of his legacy, has done.

After the ascendancy of Deng, Guangming Daily, a Chinese-language newspaper, published a special editorial on May 11, 1978 titled “Actual experience is the only standard of judging the truth”, which marked a determined shift from Mao’s previous era.

The editorial was also published by Xinhua News Agency.

It declared: “Any theory that supercedes reality and declares itself to be inviolable and not open to questioning is not scientific, and is not truly Marxism-Leninism, or Maoist Thought. Instead, it is obscurantism, blind idealism, cultural authoritarianism.”

Government has the opportunity to subject its policies to empirical and scientific scrutiny.

There must also be an appreciation of science as a critical enabler to economic reform.

Suffice to say, Government must not always be behind the curve.

It is not surprising that after being elected to head the CPC (Communist Party of China) in March 1978, Deng, who was known for determination, political astuteness and “absolute decisiveness”, convened a “National Science Conference”, where he proclaimed that science and technology are the primary productive force.

This enabled China, which was by then 15 to 20 years behind the rest of the world in many areas, to leapfrog many countries to become the second-largest economy that it is now.

Restoring the work ethic

One of the major undertakings that Government has to make is to restore the work ethic of the local workforce, particularly for public officials in both local and central Government.

Many workers cannot help but be demoralised by a culture that now prioritises nepotism over meritocracy, including a capitalist wage structure that rewards lazy people and punishes hardworkers.

Far from the presumption that work ethic is inborn, it is not: it can definitely be nurtured.

A Hong Kong scholar who visited Guangzhou, a province in China, in 1979 was surprised to notice that of the three people that had been assigned to repair the plaster of a nearby wall, one held the bucket, another applied plaster and a third one stood to watch.

Such was the work ethic then.

But Cde Mnangagwa seems to have this figured out.

In a press statement on November 21, 2017, he noted: “My desire is to join all Zimbabweans in a new era where corruption, incompetency, dereliction of duty and laziness, social and cultural decadency is not tolerated.”

Mending bridges

The standoff between Zimbabwe and the West is not sustainable. Even great wars such as World War II, which claimed between 50 million to 80 million souls, end on the negotiating table.

It was the same in China in 1978.

Before then, Chinese people were literally “locked up”, ignorant of the world around them.

At the time, while the penetration rate of television sets was 70 percent in the United States, in China it was nearly zero.

However, since the reforms, China has gradually been reaching out to the world.

As part of opening up, China on October 23, 1978 signed the Sino-Japanese Peace Accord.

Before then, the two countries had been sworn enemies, since Japan, by virtue of its reputation as an aggressor, was loathed by the Chinese people.

Similarly, on December 16, 1978, a Sino-America Communique was issued, establishing normal diplomatic relations.

It represented a determined break from ideological considerations to pragmatism, which was largely considered as a key ingredient for economic development.

Quite clearly, Zimbabwe’s Lima Plan, which is premised on normalising relations with international financiers, has been a prisoner of the sour relationship between Harare on one hand and Washington and Brussels on the other.

Now, by virtue of the new dispensation, we have a chance to fix it.

ZANU-PF: Reform or die

For ZANU-PF it is an opportunity to reform or die.

For the Communist Party of China (CPC), the turning point was the meeting from December 18 to December 22, 1978 at the Third Plenary Session of the Eleventh Central Committee of the CPC.

Notably, the assembly agreed to stop using slogans and abandoned the tendency to adulate one person and propagandise about him.

Perhaps most significantly, it came to the conclusion that “politicised life” should no longer be the basic mode of existence for the Chinese people.

For a party that is modelled along the socialist CPC, it is shocking that ZANU-PF has not been able to learn from its peers.

But now is the time; it has the opportunity to re-invent itself.

But as the Chinese model has shown, economic reforms precede political reforms for the economic wellbeing of the people is important in maintaining stability.

Though economic prospects in the new dispensation are looking up, it will definitely not be a walk in the park.

For those who have studied China’s recent history, the economic reform process was far from easy.

However, its authors knew that in order to succeed they had to indefatigably pursue reform and, at the same time, learn from their mistakes.

As fate would have it, the burden of history now rests on President Mnangagwa to put Zimbabwe back on the rails.

The script authored by history so far has been promising, only the future will tell whether it will repeat itself.

Feedback: [email protected]

Twitter Handle: DMusaru

Comments