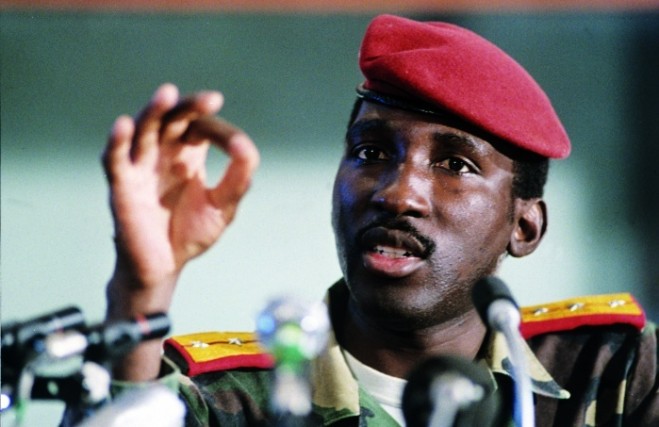

Reviving Thomas Sankara’s spirit

Hisham Aidi

THOMAS Sankara, who ruled Burkina Faso from 1983 to 1987, was one of the most riveting leaders of the last half-century. A pan-Africanist, Marxist and gifted orator, he came to power following a coup and promptly began implementing a progressive political agenda.

He changed his homeland’s name from the colonial Upper Volta to Burkina Faso, which means “the land of the upright people”. He strove to make the West African nation economically self-sufficient, promoting local industry and food security, redistributing land from landlords to peasants. He also promoted gender equality, proscribing polygamy and female circumcision. And he spoke out passionately against South African apartheid, and Western meddling in Africa.

Sankara’s radicalism electrified Africa and the Third World more broadly – in September 1984 he was awarded the Jose Marti Order, the highest honour of the Cuban government.

But his attacks on capitalism and French and US interventionism also made him powerful enemies (he once publicly repudiated French President Francois Mitterrand at a state dinner for hosting an apartheid-era South African head of state).

On October 15, 1987, armed gunmen burst into Sankara’s office, murdering the president and his 12 aides. His Minister of Defence Blaise Compaore would take over as head of state, and swiftly issue a statement – and death certificate — describing Sankara’s demise as a “natural death”.

But less than a month later, the magazine Jeune Afrique revealed that Sankara and his aides were actually murdered, their bodies dumped in a landfill outside the capital Ouagadougou.

Sankara’s widow, Mariam, has long called for an investigation into her husband’s death – asking that the remains be tested to assess whether they are indeed the remains of the former president, but for 27 years Compaore blocked all such efforts, saying “the facts are known” and that he has “nothing to hide”.

Sankara has long been a hero to youth across the African continent. The vision that he advanced of internationalism and pan-African humanism resonated profoundly.

As he would tell an audience in Harlem in 1984: “Our struggle is a call for building. But our demand is not to build a world for blacks alone and against other men. As black people, we want to teach other people how to love each other.”

Sankara’s name is often uttered in the same breath as that of Patrice Lumumba, another anti-colonial leader who was assassinated. The Cote d’Ivoire reggae star Alpha Blondy would even compose a song about the betrayal of “Captain Sankara”.

Sankara’s name often rings out when democratic protests take place, at moments when change seems possible, as occurred recently in his land of birth.

In October 2014, Compaore was overthrown in a popular uprising as hundreds of thousands of youth took to the streets of Burkina Faso protesting the dictator’s attempt to run for re-election.

The protesters would form a movement called Balai Citoyen (Citizen’s Broom), and after sweeping Compaore from power, began calling for a democratic society as envisioned by Sankara.

Last month, 10 political parties and “Sankarist” associations claiming to represent the late leader’s progressive vision formed an alliance. These groups then forged a unity agreement and put forth a candidate Me Benewende Stanislas Sankara (no relation to the late revolutionary), who publicly demanded that an inquiry be opened into the coup of October 1987.

Michel Kafando, the head of the current interim government, has agreed, seeing a resolution of Sankara’s death as necessary for national reconciliation — and as a way to smooth the country’s transition to democracy. National elections are planned for October 2015.

A judicial order was issued, and on May 25, state workers began exhuming the body of Sankara and his 12 colleagues at the Daghnoen cemetery.

Experts will test the remains against DNA samples submitted by Sankara’s sons Philippe and Auguste, both of whom are currently students in the United States. Kafando has also asked France to declassify the archives concerning Sankara’s death.

The question now is whether the Burkinabe judiciary will go beyond exhuming Sankara’s remains, and start calling high-ranking officials to testify in court over what happened in October 1987.

The Sankarist movement is now demanding that the interim government subpoena the former dictator Compaore — in exile in the Cote d’Ivoire – and his former Chief of Staff Gilbert Diendere who apparently led the commando raid against Sankara’s office — and still lives in the Burkinabe capital, to appear in court.

It remains to be seen if the interim government has the capacity — and international support — to do so. The next step for the activists is to connect with sympathisers and champions of Sankara beyond Burkina Faso’s borders.

As Cherriff Sy, head of the national transition council, put it: “We believe that the case of Thomas Sankara is not the case of the Sankara family, or of Burkina Faso, but a case [of interest] for all of Africa, because all African youth want to know why this figure of hope was extinguished.” — Al Jazeera.

Hisham Aidi teaches at Columbia University. He is the author of the critically acclaimed Rebel Music: Race, Empire and the New Muslim Youth Culture, a study of black internationalism and global youth culture.

Comments