To work or to be employed, that is the big question?

Joram Nyathi

THERE is apparently a desire to make a dystopia of the current state of Zimbabwe. This is contrasted with a romanticised past, that is pre-Independence Zimbabwe where blacks lived so well under white minority rule we should have maintained the status quo. From this thought process, everything which could go wrong has gone wrong with Independence and majority rule, hence the dystopian view of life.

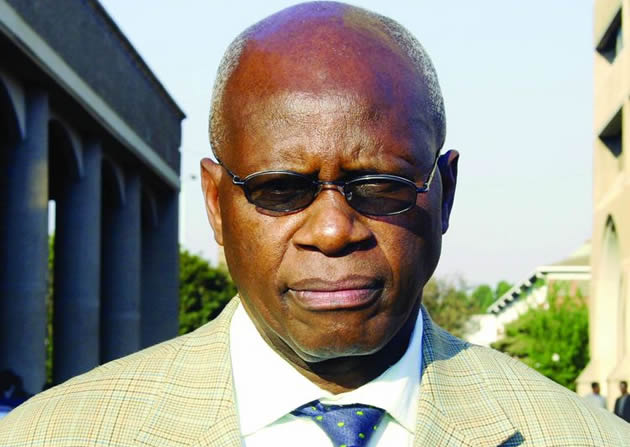

I shall cite two incidents which occurred last week. Otherwise there are legion such grim tales. The first case was highlighted by Finance and Economic Development minister Patrick Chinamasa when he addressed a CZI economic outlook symposium in Harare last week where he asked whether the country had any entrepreneurs or “industrialists in the truest sense of the word”? The second was an ILO report which put the rate of unemployment in Zimbabwe at 5,42 percent.

Minister Chinamasa said most captains of industry lacked resourcefulness to keep their organisations afloat even as they enjoyed lavish lifestyles which were not commensurate with the health of their companies. The minister noted that the difficult economic conditions in the country called for innovation rather than managers of foreign firms disposed to “moaning and blaming everybody”.

It is not hard to understand why the minister felt such frustration. There is too much focus by these managers on politics rather than what they should be doing – running businesses. Since the visit by these business executives to Europe last year, the country has received business delegations from Britain, the US, China, Russia, Sweden and lately from France, scouting for investment opportunities.

Invariably, the business delegations are forced to engage government directly to be appraised on policy issues because those who should be our local front-men can’t explain anything. While they complain about indigenisation and economic empowerment laws deterring foreign direct investment, that is not exactly the view of the foreign delegations who have investments in Qatar and Botswana where locals retain 80 percent control, not just 51 percent as in Zimbabwe.

What is being exposed more than anything else is that most of our managers are just that, managers of foreign-owned entities who moan about the operating environment to justify their failure to make super-profits for the owners. Thus they are forced to retrench. You would not believe they were operating in the same environment as Econet whose diversification has turned it into a household name in the remotest parts of the country.

Over the years we have been told of how neighbouring countries have better policies which attract new merchants of FDI. Zambia and Mozambique are often cited in the region. Local mining firms complain about paying royalties as low as five percent. But we will never be told that Zambia hiked copper mining royalties from 6 percent to 20 percent starting January 1, 2015. And newly-elected President Edgar Lungu has declared that he wants to pursue his predecessor Michael Sata’s “pro-poor policies”.

As Mining.Com observes; “Lungu’s move underscores a growing trend across the continent where governments, from Tanzania to Guinea, are changing tax regimes and adjusting ownership structures to get a larger share of natural resources.” We are being told instead to reverse the trend.

Closer to home in South Africa, President Jacob Zuma was forced to concede recently that using kid gloves to resolve the land issue in that country was not working. It is in fact whites who feel blacks want to encroach on their land, so the willing seller, willing buyer is failing. Instead the South African government is told to focus its attention elsewhere — it must create jobs for its black poor. Land is for whites, let blacks eat the rainbow! Thanks Malema for EFF.

Local managers are the first to paint the gloomiest picture of the country’s economic prospects, citing labour laws, country risks, lack of property rights and political uncertainty, those issues over which they have little control, not their own personal deficiencies. Said Minister Chinamasa; “An economy where you only have foreign firms cannot sustain itself.” Which should be a mundane observation really if we had entrepreneurs.

Which is where I believe Dimaf funds have to be used intelligently. Let us accept the fact that companies and their products have a life cycle, and that because internal and external environments change constantly, short of innovation, new technologies, new products and intelligent diversification, they are bound to die. Not all Rhodesian companies were fated to survive forever in the changed political circumstances of the “new normal” dominated by the small trader we derisively call “dealer”, an uncompetitive dollarised economy, cheap foreign imports, an economy where the small farmer has taken over from Nicolle.

Zimbabwe is so obsessed with a past we romanticise to a point of failure to imagine a better tomorrow. We refuse to dream. There is nostalgia about big company names which have disappeared because they could not withstand the gusts of liberalisation which came with Esap. No amount of moaning will bring them back. Some companies must die. Zimbabwe’s economic recovery cannot be predicated solely on increased capacity utilisation by dying companies when new ones are being born everyday but are starved of financial support by government.

Obsession with Rhodesia has become a huge mental burden weighing down on our ability to conceive a better future — the smallholder farmer who needs funding for inputs and mechanisation to feed the nation; the small electronics engineer, motor mechanic, plumber, metal fabricator, the young men who make gates for our yards, the builder and carpenter who wants money to equip his workshop. These are the small businesses which provide the services which used to be offered by big white monopolies not long back. They have skills; they want resources to grow. They are fighting mental slavery, the “employ me baas” syndrome.

Most of the people supplying chicken on the market today were probably poor employees of Crestbreeders and Irvine’s five years ago. They aspire to replace those white monopolies. What they require is a little government funding, not crippling taxes by Zimra.

Which brings us to the ILO’s unemployment figures. On January 26, 2015, the Bulawayo-based Southern Sun ran a story critical of International Labour Organisation figures which said the rate of unemployment in Zimbabwe was as low as 5.42 percent. This came from a survey they conducted; it had nothing to do with Zanu-PF or Nikuv. Still the figures were described as “misleading” because they did not fit into the dystopian view of Zimbabwe.

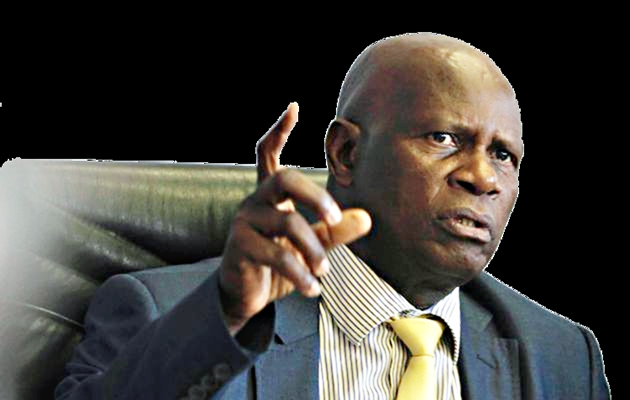

And who better to confute these statistics than the doyen classical Rhodesian capitalist economic model, John Robertson, raw from college untainted by the noise from Tony Hawkins’ “new normal” and Anderson’s “imagined communities” of a transforming Zimbabwe.

Where are 95 percent of the people working as industries and companies are closing shop everyday? the paper wanted to know. Never mind that it is in the public domain that the “new normal” in the “informal sector” has 5.7 million doing business everyday. Sithembiso Nyoni told us last year that $7 billion was circulating in that informal economy. Shouldn’t government be focusing its attention on that sector?

The 5,7 million are not employment, says Robertson the economist. They are unemployment. “When we talk of employment, one should be working in an incorporated company with formal structures, registered and known by the tax collector,” he said.

“Even communal farmers who I know are part of the employment figures are not working for incorporated companies and I would not say they are employed.”

Perhaps Robertson has a point. Communal farmers who pay school fees for their children from their farm produce and animals are not employed. They are working. The employed are the often touted 500,000 commercial farm workers of pre-2000 who couldn’t afford to send their children to school. Those were the employed Zanu-PF disturbed through its land reform.

In equal measure, we should despise mechanics, builders, carpenters, plumbers etc who are part of the 5,7 million Zimbabweans exchanging $7 billion annually because they are not employed by an incorporated company.

Even if they can make $700 by selling a single gate and a teacher earns $450 per month. To work or to be employed, that is the question?

Comments