What’s in a Name?

Crystabel Chikayi

CAN a name really influence how one thinks, behaves or shape one’s destiny?

Mr Bayanai Tshuma, a Bulawayo man based in South Africa seems to thinks so.

He is suing the Registrar-General, Mr Tobaiwa Mudede, for allegedly denying him a new birth certificate with a new first name. Mr Tshuma wants to be renamed Norman.

During childhood people are often said that a name is a proper noun and it consolidates an individual’s identity. Others say a name denotes nationality and is an embodiment of, among other things, culture, character and taste.

But could there be more to a name?

Dr Nhlanhla Landa, a linguist based in Bindura, says the process of naming is deliberate as parents name their children in relation to their life’s experiences.

The experiences can be centred on their beliefs, frustrations, aspirations and special events.

Historic names, Dr Landa says, are pointers to one’s origins.

“In our day to day lives we come across individuals who rename themselves. Mostly these people would have decided that they do not want to associate themselves with their history and emotions linked to their names.

“There is what we call self-naming whereby one gives himself a pseudonym like ‘the Anointed’.

“One might never be able to know who the real person behind that pseudonym is but a pseudo name always reveals one’s character and feelings,” said Dr Landa.

Human naming is believed to be coloured by passion, fear, pride, hope, lust and at times experience.

Dr Landa says the effects of names on their bearers are psychological.

“There is what we call an ‘effect’ whereby when a person does well and you say well done, it motivates him or her. These effects do not work the same with everyone because the bearer of the name makes a conscious decision to break the impact of the name.

That is why you can find a very rich man with a name like Mhlupheki. Some, however, fail to surpass the belief that their names curse them,” he said.

Mr Tshuma, whose first name Bayanai is Shona for “stab each other”, is convinced his name is cursed.

He argued in his court papers that he continuously suffers bad luck because of his forename.

Some prominent people find it difficult to live with their given full-names when they make it in life. They then opt to either shorten the name or rename themselves.

For example, former Minister of Environment and Tourism, Cde Chenhamo Chakezha Chimutengwende, is widely known as ‘Chen’ short for Chenhamo.

A rare few like Mr Tshuma prefer changing their first names officially by getting a new birth certificate with a new name.

Linguists say not all acts of naming are innocent, sometimes they shape and form the bearers of such names, be it human or animal. Last week a 24-year-old man, Sifeluthando Khumalo, from Entumbane Suburb in Bulawayo, appeared at the West Commonage court facing a charge of having sex with a minor, his 13-year-old lover.

Khumalo’s first name in IsiNdebele means “dying for love”. His case is still before the courts. Parents are often blamed for giving their children unusual or controversial names.

Experts say a number of kids are named based on what will be trending at the time the child is born while some parents may name their children after their favourite singers and soccer stars.

Mr Vengesai Nhau of Bulawayo says at times forenames assume the form of a message in a polygamous setup. He says his father has three wives with his mother being the senior wife.

“I have two brothers from my step-mothers who are younger than me. One is called Tirivafi (we are corpses) and the other is Tirivapi (who are we?).

It was our mothers who named us but they never really told us why they chose those particular names,” said Mr Nhau whose first name, Vengesai, means “hate all you want”.

Traditionalists say the naming process is a documentation process as names capture history and time.

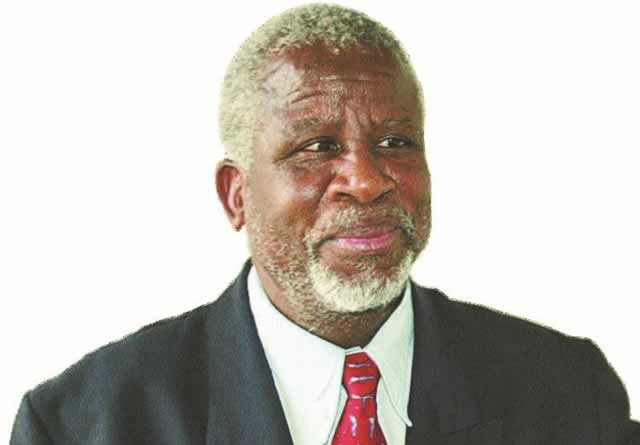

Mr Phathisa Nyathi, a cultural fundi and renowned historian, says names are not taken from a basket like fruits. Children are named in relation to circumstances, situations or events that would be there during their time of birth, he says.

“Traditionally a new born baby is not named or allowed to come out of the house before the new moon has appeared and before the umbilical code has fallen.

“When the child has not yet been out of the house we say usesengamanzi meaning, he is still water.

“We only name a child when he or she is strong enough and it is certain that the child will live,” said Mr Nyathi.

He says a child is not just named for the sake it but to preserve history. Said Mr Nyathi: “If a child is born during a drought, he might be named ‘Ndlalambi’ as a reminder that the child was born during a severe drought.

Our tradition does not label time with digits to say 2000 or 1999. We tell time in relation to events.

The name Masotsha may just be a reflection that the child was born when the soldiers were active during the colonial era.”

A traditional healer, Mr Simon Sibanda, says children are named in relation to situations at home at their time of birth. He says a name has the power to influence character and destiny.

“When a girl child is given her late paternal aunt’s name, because of their blood ties, the spirit of the dead aunt enters the child. She starts behaving just like her aunt used to. In such a case the child adopts both the negative and positive traits that the aunt had, ” said Khulu Sibanda.

Reverend Paul Bayethe Damasane says Christianity defines the naming process as the ascribing of a reference to an object or someone. When naming something, he says, you make it belong to someone.

“Names can be prophetic or descriptive. The process of naming has a lot to do with what has happened.

“It can have a bearing on an individual in the sense that, a name can be a burden to the child. Naming is critical as it can make one acceptable or repulsive.

For example, Cde Obedingwa Mguni became the first Zanu-PF MP after a chain of MDC MPs in his constituency (Mangwe).

His name Obedingwa, which means the exact person we have been looking for, fits very well into the situation,” said Rev Damasane. He says christening in Africa came as a result of the western tradition whereby people change their names to adopt patron saints’ names.

Said Rev Damasane: “Europeans changed indigenous people’s names to English because they could not pronounce the local names. An English name is not necessarily a Christian name.”

He says Christian names are given to people who already have their family names and they are given as a way of linking individuals to their new found identity.

“A name links the individual to the past, creates an active present and reflects a better future,” said Rev Damasane. He says today’s naming does not differ much with the traditional way.

“Parents today still name their children in relation with the situations around but simply change the name to English. You find that a parent at the back of her mind wants to call her child Velile but translates that to English and end up calling him Obvious.

The old traditional art of naming still remains but we have westernised it. That is why you find many kids with English names that make no sense at all,” said Rev Damasane.

Mrs Silobile Sithole (34) of Makokoba openly despises her name which is an expression of disappointment. Her name means “we have become very scarce”. She says her parents named her after losing a son in the year she was born.

Mrs Sithole said: “My parents hoped I was going to be a boy. A name is something one should be proud of, but I hesitate to mention mine in public.

“At school people would make fun of my name. I thought of changing it because it has given me bad luck in the past years, but changing it is costly. I completed my degree in English and Communication in 2009 but I have never been permanently employed ever since.” — @cchikayi.

Comments