Zambia played big role in liberating blacks

Opinion Saul Gwakuba Ndlovu

Yesterday, October 24, was the 50th anniversary of Zambia’s independence, a political development that made the Zimbabwean liberation struggle relatively easier than it would have been had its northern neighbour remained under Britain’s colonial rule much longer.

Zambia was formerly known as Northern Rhodesia, a colonial name given to it in honour of the notorious British arch-colonialist Cecil John Rhodes, whose company, the British South Africa (Chartered) Company, had planned and led the seizure of large tracts of land south and north of the Zambezi River on Britain’s behalf since 1889 to the time of his death in 1902.

The land south of the Zambezi was called Southern Rhodesia also in his honour. Today it is named Zimbabwe. It achieved its independence on April 18, 1980, some 16 years after the birth of Zambia.

In 1953, Northern Rhodesia, Southern Rhodesia and Nyasaland were grouped together into a British colonial territory known as the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. That was officially dismantled on December 31, 1963 and Nyasaland became independent on July 6, 1964, about four months before Zambia.

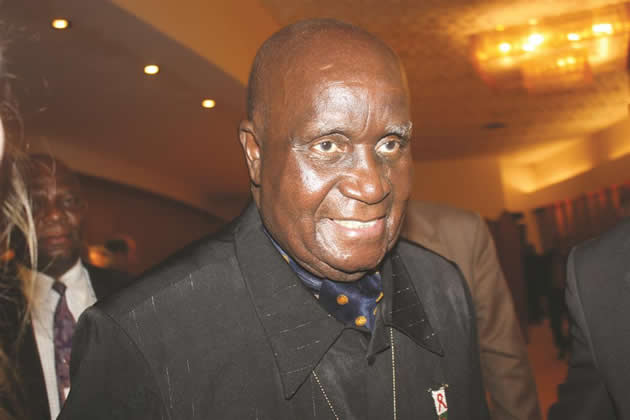

Zambia’s founding Head of State was Dr Kenneth David Kaunda. His political organisation, the United National Independence Party (UNIP), had mounted a militant campaign code-named “Chachacha” to make the country ungovernable to the British colonial administrators.

Kaunda had earlier been a senior official of the African National Congress (ANC) of Northern Rhodesia led by Harry Nkumbula but had broken away with a number of radical young men who did not like Nkumbula’s lethargic kind of leadership. The break-away group formed first a party they called the Zambia African National Congress (Zanc) which was soon banned, and was succeeded by Unip.

Kaunda and his team were highly motivated and had clearly identifiable pan-Africanist goals some of which were spelt out by the historic 1958 Accra Pan-African Conference chaired by Ghana’s first president, Dr Kwame Nkrumah.

One of that conference’s resolutions was that independent African states must actively help those still under colonial domination to be free. Before the formation of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), Kaunda was the secretary of what was called the Pan-African Movement for East, Central and East Africa (Pafmesca) based in Dar es Salaam

Among prominent founders and officials of that organisation which was dissolved soon after the inauguration of the OAU in 1963 were Tanzania’s Dr Julius Nyerere, Rashid Kawawa, Uganda’s Dr Milton Obote, Kenya’s Mzee Jomo Kenyatta and a few other national leaders from South Africa, Swaziland (Dr Ambrose Zwana) and from Rwanda and Burundi.

When Zambia became independent, the eyes and ears of the world were on Rhodesia whose regime led by Ian Smith was actually threatening to declare independence unilaterally.

The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland had just been folded up, and its assets and liabilities had been duly apportioned. What had shocked the Afro-Asian nations in particular was that the Federal Air Force equipment, that is to say bombers and all, were handed over by the British government to the Rhodesian administration in spite of its repeated threats to seize independence illegally.

Meanwhile, Zambia was firmly demanding the democratisation of the Rhodesian government and that it was morally bound to support the black majority of the people of Zimbabwe.

The United Nations, the Commonwealth, the OAU, the Non-Aligned Movement, the Afro-Asian People’s Organisation (AAPSO) protested to Britain about the matter. The protests fell on deaf ears.

Those bombers were later used by the Smith regime to bomb refugee camps in Zambia and Mozambique. However, those countries together with Botswana, and, of course, Tanzania stood firm in support of the freedom fighters of Zimbabwe.

When Zambia became independent, the vast majority of the black people were living in indescribable squalor as well as below the poverty datum line. That was in spite of the fact that Zambia is a world-renowned mineral-rich country.

However, that massive wealth was sucked from the bowels of the country and sent to Britain, the United States, Australia, Belgium, France and elsewhere overseas, leaving the natural owners of the resources to live in hovels such as those that were at Lusaka’s Chibolya (the rotten place), Old Kabwata, Roberts Compound and elsewhere.

There was an agreement between the BSAC as “owners of the country’s minerals” and the Northern Rhodesian colonial government that the BSAC would pay the administration £7 million yearly but continue owning the minerals.

On assuming office, Kaunda urgently dealt with that scandalous issue by taking the matter to court.

The court ruled that the ownership of the country’s minerals should be under the Zambian government, and that the BSAC should be compensated to the tune of £4 million, half of which was to be paid by the British government and half by the Zambian state.

As the Rhodesian crisis got worse, it became obvious that Zambia would sooner than later be unable to use the railway line through Rhodesia to the seaports in either Mozambique or South Africa.

So, Kaunda and his highly motivated government team negotiated with China to build a railway from Zambia to Dar es Salaam, a distance of just about 1,696km.

During the federal decade, a university college was built in Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia, and a few Zambian students had graduated there. The crisis in Salisbury, now Harare, made it impossible for Zambians to continue studying at that institution.

So the Zambia government constructed a national university in Lusaka. A university teaching hospital was also built, and so were hundreds of primary and secondary schools were put in every province.

Before independence, Zambia imported sugar from Rhodesia. Soon after independence it established its own sugar estate, the Nakambala Sugar Estate near Mazibuka in that country’s Southern Province.

In the transport sector, in addition to the Chinese-built railway line from Kampiri Mposhi to Dar es Salaam, Zambia built a modern, big airport just outside Lusaka, the Lusaka International Airport.

The nations of western Europe tried to sabotage Zambia’s socio-economic development in the early 1970s to show their strong disapproval of that country’s support of the liberation struggle of the people of Zimbabwe, Namibia, South Africa, Angola and Mozambique as well as those of Southern Sudan.

Their attempt to derail Zambia’s development programme was by reducing the price of copper at international markets.

Copper is Zambia’s major export commodity. The attempt did not deter the Zambian government from practically continuing its solidarity with the black people of those formerly colonised nations.

While each of those nations heartily thanks Zambia and congratulates it on its golden independence anniversary, the Zambia nation is, I am sure, rightly feeling a sense of deep satisfaction and pride, especially its great leader Kenneth David Kaunda, that it played a big role in the liberation of most of the black people of Southern Africa.

- Saul Gwakuba Ndlovu is a Bulawayo-based retired journalist. He can be contacted on cell 0734328136.

Comments