Africa has huge potential for agriculture

Agriculture is not glamorous. It suffers from entrenched negative perceptions. In the minds of many African youths, a farmer is someone like their parents, doing backbreaking labour in the fields and getting little to show for it. Nonetheless, agriculture is the engine driving many African economies. If it were to get the same political support and financial investment as the mining sector, agriculture would be capable of providing more decent jobs and filling millions more stomachs with nutritious meals.

Agriculture is not glamorous. It suffers from entrenched negative perceptions. In the minds of many African youths, a farmer is someone like their parents, doing backbreaking labour in the fields and getting little to show for it. Nonetheless, agriculture is the engine driving many African economies. If it were to get the same political support and financial investment as the mining sector, agriculture would be capable of providing more decent jobs and filling millions more stomachs with nutritious meals.

Francisca Ansah, an extension officer with expertise in agriculture and rural services, works with farmers in the Upper West region of Ghana. At a farmers’ conference in Ghana last year, she said the image of poor, ragged and weather-beaten farmers puts off many young people. Having seen their aging parents go through the traumatic experience of farming using basic equipment, these young people opt to settle in urban areas in search of employment.

“Young people have second thoughts about agriculture as the source for jobs,” said Ansah.

Despite the negative perceptions, the agricultural sector employs as much as 60 percent of Africa’s labour force, according to the Africa Economic Outlook Report 2013, published jointly by the African Development Bank, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the UN Development Programme. Yet because of low productivity, the sector accounts for only 25 percent of the continent’s gross domestic product (GDP).

Despite such grim statistics, the sector has huge potential. The World Bank estimates that African agriculture and agribusiness could be worth $1 trillion by 2030.

For that to happen, there must be improvements in electricity and irrigation, coupled with smart business and trade policies. An agribusiness private sector working

alongside government could link farmers with consumers and create many jobs.

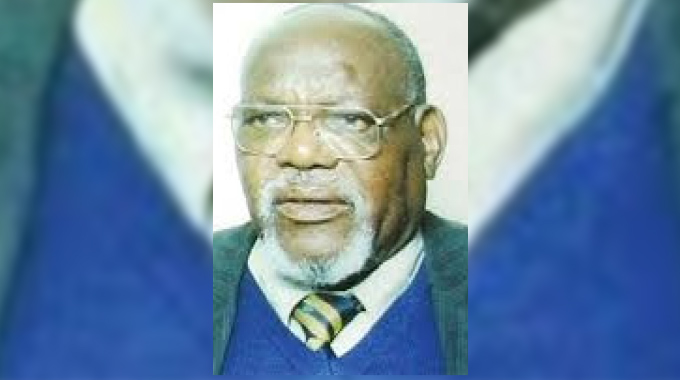

Fast-growing economies that can cut poverty and create meaningful jobs, particularly for youths, require political will from leaders and huge injections of investment in agriculture, according to Professor Mandivamba Rukuni, a Zimbabwean researcher and land policy analyst.

“Africa is still on average 60 percent rural in population. The African Union has defined the immediate future around agriculture as the main force in social and economic transformation of the continent,” says Prof Rukuni, who has published widely on African agriculture.

“Africa’s economies have been growing sustainably since 1999, agriculture has also been growing, but at a slower rate,” he says, adding that the continent has been the slowest region in its efforts to eradicate poverty.

He emphasizes the need for governments to focus on adding value to agriculture and to form partnerships with the private sector and set joint targets. On how governments and the private sector could work together, Prof Rukuni says, “Look at China, India and Brazil: there is no distinction between government and private sector.”

Africa’s lack of competitiveness in agriculture is a drag on efforts to boost employment in this sector.

Prof Rukuni describes competitiveness as involving “what the government is prepared to do to support its producers to gain access to their markets.” His solutions include boosting rural development through a chain of activities that add value to agricultural products, providing necessary infrastructure to stem urban migration and empowering women and youths to run small businesses.

Marco Wopereis, deputy director-general at the Cotonou-based Africa Rice Centre in Benin, says innovations in agriculture could unlock vast employment opportunities. The rice sector alone has the potential to employ many of the 17 million young people who enter the job market in sub-Saharan Africa each year. With financial support and training programmes, young rice farmers could boost rice production and add value to it, said Wopereis in an interview with Africa Renewal.

“With so many people without a job, the rice sector in Africa is a golden opportunity to provide jobs.”

Many experts have expressed alarm over Africa’s growing youth unemployment. Ibrahim Mayaki, chief executive officer of the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD), the African Union’s development agency, calls youth unemployment a “time bomb.” Sub-Saharan Africa’s youth population is increasing rapidly, with the 15- to 24-year-old age group at 200 million, a figure that is expected to double by 2045, according to population experts. But agriculture could potentially provide enough food and jobs.

In a 2013 report, Agriculture as a Sector of Opportunity for Young People in Africa, the World Bank added its voice to data by other organisations showing that agriculture is Africa’s largest employer and has the potential to absorb millions of new job seekers. According to the report, increased focus on agriculture could enhance productivity, reduce food prices, increase incomes and create employment. Young people’s involvement in this process is crucial.

“Although farming is now often done by the elderly, the profession’s requirements for energy, innovation, and physical strength make it ideally suited for those in the 15 to 34-year age range, that is, ‘the mature young,’” notes the Bank.

The consensus among experts is that for agriculture to create high employment, young people must get involved.

Strive Masiyiwa, chair of the board of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), a continental body involved in assisting small-scale farmers across Africa, says it is possible for agriculture to be both more productive and hip enough to attract young farmers.

“My vision is that the smallholder farmer may still work the land . . . they will be using new seeds, fertilisers, modern methods, they will be young, they will be skilled and have cars outside their houses and market information on prices of their produce.” Agriculture has to be dynamic and profitable to attract youths, he adds.

To support this vision, AGRA is mobilising 450 farmers’ organisations in 14 countries to give smallholder farmers market access and bargaining power for their produce. Thousands of such farmers in African countries where AGRA operates already have easy access to improved seeds of staple crops, fertilisers, markets, and finance are reaping the benefits of improved soil and water management. In Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, for example, 295,000 farmers have been trained in fertiliser micro-dosing (the process of applying small doses of fertiliser on crops) and ways to improve the soil and the yield of food staples such as sorghum. The hope is that as these farmers scale up their activities, thousands of the unemployed will find jobs.

Over the years Africa’s agriculture has travelled a bumpy road. Obstacles have included the global economic crisis, food price spikes, climate change, poor harvests, and poor storage facilities during times of plenty. The result has been the failure of agriculture to generate high job numbers and make a big dent in poverty.

The African agricultural plan known as the Comprehensive African Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) is intended to bring about jobs, large economic gains, a reduction in hunger and, through increased productivity, a reduction in food imports. Under CAADP, which was adopted in 2003, African leaders committed to allocate at least 10 percent of their national budgets to agriculture and rural development.

Of Africa’s 54 countries, only nine including Burkina Faso, Malawi, Mali, Ethiopia, Niger and Guinea, have to date invested 10 percent of their national budgets in agriculture. But Africa has huge agriculture potential. The World Bank estimates that the region has more than 50 percent of the world’s fertile and unused land.

Sub-Saharan Africa alone has some 24 percent of the world’s land with rain-fed crop production potential. Besides, foreign direct investment in African agriculture is forecast to grow from less than $10 billion in 2010 to more than $45 billion in 2020.

A robust agricultural sector is necessary for sustained economic growth and high-paying jobs in Africa, according to the International Labour Organisation. Making it a reality is a major task for the next 10 to 20 years. – Africa Renewal.

Comments