Broadcaster influenced 13-yr-old to join struggle

Yoliswa Dube-Moyo

IT was the culmination of a dream that the black majority would choose their own government when the Union Jack was lowered and the Zimbabwe flag hoisted at Rufaro Stadium in Harare on April 18, 1980.

Sleeping in the trenches and sharing a home with animals became worth it for the many foot soldiers who fought tirelessly to liberate the country from white minority rule.

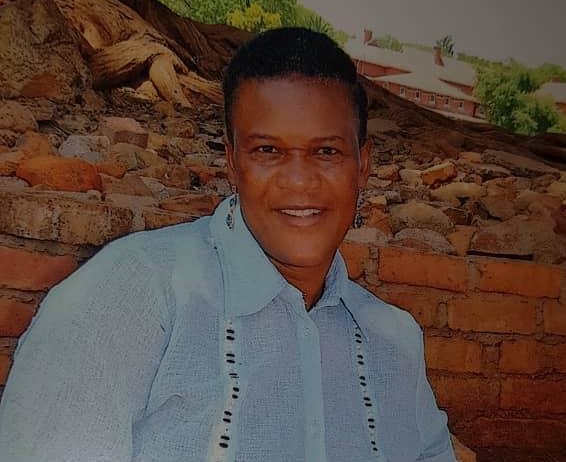

When legendary Jamaican musician Bob Marley sang, “Every man got a right to decide his own destiny” during the performance of his song “Zimbabwe”, at the Independence celebrations in 1980, ex-combatants and war time musicians like Cde Happiness Sibanda (57), could not hold back tears of joy.

Cde Sibanda, a member of Light Machine Gun, a choir set up by the late Vice President, Dr Joshua Nkomo to motivate freedom fighters during the protracted war of liberation, was one of the many who were flooded with mixed emotions when Prince Charles lowered the Union Jack.

The pain harmonised by Light Machine Gun in its song, “Kubuhlungu emoyeni” turned into “Sijabule namhlanje, siyithethe iZimbabwe”, as the liberation fighters had won the fight against white oppression.

The country’s road to independence remains fresh in Cde Sibanda’s mind who joined the struggle when she was only 13-years-old.

“I got interested in the politics of the time because I hated how the whites were treating us. My greatest influencer though was a broadcaster, John Mbedzi. I’d hear him talking on the radio and he would emphasise the importance of the war,” said Cde Sibanda.

She said her interest peaked all the more as she saw people pass through her home area in transit to join the liberation struggle.

“I come from Beitbridge, in the Shashe area. I used to herd cattle and would bump into people who needed to be shown directions to Botswana. Where I come from was a crossing point for ex-combatants going into Botswana. This one day, a group of about 60 people passed through and I decided I wasn’t remaining behind,” said Cde Sibanda.

Cde Hapiness Sibanda

She continued: “I was 13-years-old when I joined the liberation struggle. We experienced a lot of difficulties. There was no food or shelter and we did really tough exercises. The most difficult exercise was the number nine where you would hop like a frog. This was usually given as punishment — maybe you’d have stolen some guavas and were caught; when you were caught, you’d be punished because you’d be eating before the other soldiers had eaten.”

When one left the country to join the liberation struggle, they were first taken to Selibe Phikwe in Botswana before they were ferried to Zambia via “Dakota”, an aeroplane.

“I stayed in Botswana for a month before crossing to Victory Camp, our first camp in Zambia. It was a transit camp,” she said.

Every woman who went to Zambia went through Victory Camp.

“We would wake up early in the morning to do some exercises, skirmishing and some shooting. There were shooting areas. Each and every woman who went to the war, before you went to Mkushi (Camp), you were at Victory Camp. That’s where the training was done. The guerilla warfare started at Victory. Mkushi was more of a finishing area,” said Cde Sibanda.

Due to the intensity of the physical training the female ex-combatants underwent, many of them stopped menstruating, somewhat taking away a part of their femininity.

“There was no sanitary ware but also because of the exercises we did, we stopped menstruating. All the girls stopped menstruating because of the type of exercises we did in the morning. We all ceased being “normal women”.

The exercise regime was taxing and took a toll on Cde Sibanda and the other comrades in the struggle. “We would toyi toyi among other exercises. After the initial training, we went to Mkushi Camp. The training was the same for both sexes; it didn’t matter whether you were a man or a woman. If your company, platoon or section was exercising, you were part of it. There was no distinction of being male or female. That’s why I’m saying we stopped menstruating because of the toughness of the exercises so no one would request for sanitary wear,” said Cde Sibanda.

Aside from physical training, lessons were also conducted at Victory Camp as more youngsters went to Zambia to join the liberation struggle.

“Not everyone could be accommodated at Mkushi. There were some teachers taking children through the normal education system at Victory. Also, the liberation struggle was not all physical. There was time to sit down and learn what the struggle entailed. We also had time to learn about the history of the liberation struggle and things like that,” said Cde Sibanda.

She is still traumatised by the bombardments she witnessed at Mkushi Camp and has scars which serve as a constant reminder of her experience in the trenches.

“What affected us the most were the bombardments. You would be talking to someone and the next thing their intestines are out, the head has separated from the body and the hand is in another direction,” said Cde Sibanda.

One morning of 1978 at Mkushi Camp remains vivid in her mind.

“Our camp was bombed. We could see people moving around during the night and as a signal, you’d shout “hold!” If the person didn’t stop, you knew they were a sell out because they didn’t know our language.

“These guys (Selous Scouts) would come during the night. The day we were bombed, we had been called to assemble. A whistle was blown as usual and we ran to the gathering point, little did we know that it was a trap. And when they bombed us in such a scenario, you’d be lucky to be alive. They held our commander Jane hostage in their aeroplane.

“Jane shouted “phumanini!” but we didn’t know that when she was telling us to come out, she was under duress. When you hear your commander’s voice, what do you do, you have to come out, so we did that. We thought it was a genuine “phumanini”. People came out and many of them were killed,” recalled Cde Sibanda.

The liberation fighters slept in tents or trenches stretching about 500m to allow them to hide whenever the enemy came.

“There was a small aeroplane, we called it a spotter. It would come for about an hour and take pictures of us. The moment it did that, we knew we had to brace for bombing,” she said.

After attacks, Cde Sibanda and other cadres would assemble for a head count.

“We would go there to identify each other. We knew each other by our struggle names and because we were divided into companies, it was easy to tell after some days who was missing,” she said.

Using your real name during the liberation struggle was risky.

“I was known as Kunzima Ekhaya. The moment you got into a camp, you were given a name. This was because the Selous Scouts, the spies, would also join the struggle but when they came back from the struggle, they’d kill your parents. So the moment you got into the camp, you’d change your name so that you were not easily identified. If you told a spy your name was Kunzima Ekhaya, they wouldn’t know whose child you were,” said Cde Sibanda.

After sustaining injuries during the Mkushi bombing in 1978, Cde Sibanda went back to Victory Camp for further treatment and later joined the choir, Light Machine Gun.

Light Machine Gun fought through song. It churned out many popular songs and was there to motivate the fighters since there was no music or radio at the time.

The choir was the radio of the struggle.

“We sang plenty of songs to motivate the ex-combatants. Sihlezi Egangeni, Laphuma Laba Bahle, Sizogijima, Guerilla Ilanga Litshonile. They were so many of them.”

The group was made the official Zipra Choir in Zambia in 1978 and its songs turned out to be the driving force of the struggle.

Following the country’s attainment of Independence in 1980, Cde Sibanda went back to school to salvage what was left of her life.

“I went back to school in 1982. We were given money to help rebuild our lives. I worked my way through school. I did my Form One when I was 25-years-old at Fatima Secondary School. (Former President Mr) Mugabe had declared free education for all. I had to supplement my ‘O’ Levels and trained to become a teacher,” said Cde Sibanda.

In 1985, she met and later married her husband, Jimmy, with which she has four children. “LMG is still recording. It’s important for people to know that LMG is still recording,” she said. – @Yolisswa

Comments