Business-modelling PPPs for vibrant university infrastructure development

Prosper Ndlovu, Feature

ZIMBABWE’S knowledge and skills sector, largely dominated by state universities and colleges, is undergoing critical transformation following adoption of “Education 5.0” by the Ministry of Higher and Tertiary Education, Science and Technology Development.

The sector’s traditional tripartite mission of teaching, research and community service has now been revised to align to the urgent national ambition under the Second Republic led by President Mnangagwa of attaining an upper middle-income economy status by year 2030.

Higher learning institutions are now mandated not only to teach, research and render community service but to also lead in innovation and industrialising Zimbabwe.

Under Education 5.0, state universities must, in particular, drive outcome-focused national development activities towards a competitive, modern and industrialised Zimbabwe.

Essentially, the sector must champion problem-solving for value-creation, be modernisation and industrialisation champions through adoption of disruptive technologies in keeping with global trends while combining these with entrepreneurial mindset as opposed to churning out job seekers.

Clearly, this mandate demands massive infrastructure investment at universities and colleges in areas such as students’ hostels, lecture rooms, well equipped laboratories, innovation hubs, ICTs and so forth.

This would not only help incentivise retention and attraction of qualified personnel but ensure these centres are adequately equipped to render top-notch training, being able exploit available economic opportunities in host communities to realise university-linked start-ups and ultimately companies that contribute to the national purse.

National University of Science and Technology accommodation under construction.- (Picture by Fortunate Nkomo)

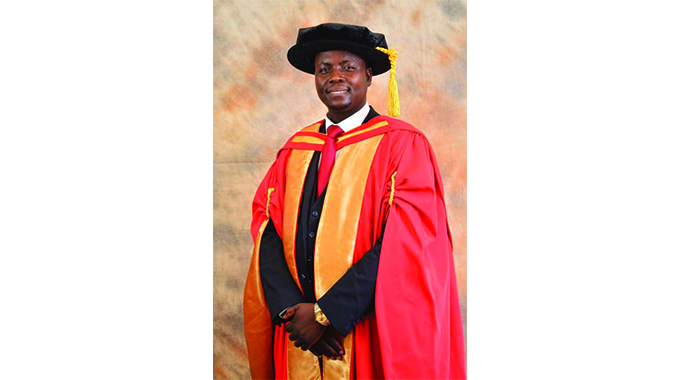

The essence of developing sound infrastructure in the country’s universities is strongly expressed in a recent study conducted by Bindura University of Science Education (BUSE) lecturer, Dr Charles Massimo, titled: “Critical Success Factor Model and the Implementation of Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) for Educational Infrastructure Development in Zimbabwe’s State Universities”.

Given limited fiscal space, the study acknowledges that the burden of developing university infrastructure could not be solely shouldered by the Government, hence the need to embrace PPPs, which are increasingly seen as a viable way to develop infrastructure on a cost effective and sustainable basis.

The study, thus, sought to understand the Zimbabwe state universities’ experiences in using PPPs for educational infrastructure development.

Through examining the evolution of PPPs as an alternative funding option for the development of educational infrastructure, it analyses the adequacy of the extant regulatory frameworks governing the implementation of infrastructure PPPs and explores critical factors hampering the uptake of the model.

The study further proposes an “Educational Infrastructure Critical Success Factor Model (EICSFM)” that could be harnessed to promote effective implementation of educational infrastructure PPPs in Zimbabwe’s state universities.

In this study, Dr Massimo argues that despite convincing empirical evidence that PPPs are feasible and capable of injecting dynamism in the public sector, the tertiary education sector, particularly State universities in Zimbabwe, are yet to fully exploit this window of opportunity amid notable educational infrastructural gaps that are visible in most institutions.

Despite the enabling policy frameworks, Dr Massimo states that there has been generally low uptake and implementation inertia of educational infrastructure PPPs in Zimbabwe state universities ever since their adoption and standardisation in 2010, as an alternative procurement approach.

“Only a few state universities have tried the approach at a sluggish pace and some have since deserted it in spite of available regulatory frameworks empowering them to embrace PPPs in infrastructure development such as the Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of Joint Venture Partnerships at State Institutions of Higher and Tertiary Education and the Joint Venture Act (Chapter 22:22),” he says.

“Many state universities, however, are yet to take up the initiative regardless of the Government’s desire to have PPPs implemented so as to reduce the infrastructure gap exacerbated by increase in student enrolment and dwindling capital budgetary support.”

According to Dr Massimo, the study findings strongly indicate that the effective implementation of PPPs in the country’s university infrastructure project is being hampered by a series of factors that need to be urgently attended to.

These include; lack of indemnities or sovereignty guarantee, dearth of prerequisite capacities to handle PPPs within the state universities, unstable macro-economic environment, limited local financial markets, lack of available financial resources for feasibility studies, absence of land ownership rights by state universities, insufficient support from the parent ministry, and lack of bankability and attractiveness of some projects in state universities.

In order to derive tangible results, Dr Massimo suggests that the Government must take a proactive stance by putting in place a favourable business-oriented operating environment for PPPs arrangements in Zimbabwe’s state universities.

He notes, in particular, that some of the regulatory policy frameworks such as the Joint Venture Act (Chapter 22:22) are biased towards the use of PPPs for economic infrastructure instead of social infrastructure development.

Hence the newly developed Educational Infrastructure Critical Success Factor Model for implementing PPPs in Zimbabwe’s state universities provides a holistic approach towards the adoption and implementation of PPPs in institutions of higher learning.

“The study recommends that state universities should develop business-oriented approaches in their operations if they are to attract private investors in their PPP arrangements,” says Dr Massimo in his abstract.

“The research also recommends that there should be a sector specific legal and institutional regulatory framework for implementing PPPs in state universities. The study further recommended that state universities should be given land ownership rights in the form of title deeds, the domestic financial markets have to be stable, PPP projects to be bankable, and the need for transparency in the procurement process.

“If these proposed recommendations are adopted, state universities will be able to address the infrastructure challenges,” he adds.

The urgency to develop sound universities infrastructure cannot be overemphasized given the rise in student population from 2 240 in 1980 to over 200 000 students, which has exacerbated the need for investments in learning spaces, accommodation facilities, recreational and other supporting facilities, says Dr Massimo.

Citing the ministry’s Investor Handbook (2017), he notes that this number is, however, not commensurate with the available educational infrastructure, as only 15-20 percent of the student population in state institutions of higher learning can be accommodated in internal residence.

According to the Ministry Handbook, there were 69 973 students enrolled in state universities across the country by 2017 and the same source indicates that 75 percent of these had no access to on-campus accommodation facilities.

Lupane State University (LSU), which partly operates from Bulawayo, and Gwanda State University, are part of the institutions that function without adequate learning infrastructure, accommodation for students and staff, among other key infrastructure gaps. The National University of Science and Technology (Nust) has also over the years struggled to develop adequate hostels for students.

“Rapid growth in enrolment by universities has resulted in services and accommodation demands outstripping infrastructure and service capacity. About US$$3.7 billion is required to cover educational infrastructure gap in Zimbabwe institutions of higher learning,” says Dr Massimo citing official Government sources.

Also in the study, the Southern Africa Universities Association (SARUA) equally notes that Zimbabwe public universities are in priority need of teaching and laboratory spaces, administrative offices, staff accommodation as well as research facilities.

Due to implementation apathy of PPPs in this sector, Dr Massimo says that the Government has been left to be the main financier of the educational infrastructure at a time when there is limited financial space for capital projects and at the same time when universities are increasing in numbers.

“The resultant effect has been the underinvestment in educational infrastructure development in this sector; a situation that would have been alleviated through the effective implementation of PPPs,” he adds.

“Inadequacy of educational infrastructure such as teaching and laboratories space, administrative offices, staff and student accommodation, as well as research facilities has diverse implications on the quality assurance especially in state universities, which are hubs of knowledge generation.”

Further, the BUSE lecturer states that refined explanations to account for factors hampering the departure of educational infrastructure PPPs in Zimbabwe state universities have not yet been presented. Neither has the critical success factors CSFs) for its effective implementation been established, he argues.

Dr Massimo, thus, calls for robust exploration of the sector specific experiences with PPPs and the establishment sector specific CSFs for effective implementation of infrastructure projects in Zimbabwean universities.

These will be more crucial if the expected outcomes of PPP to break the inter- generational transmission of educational infrastructure shortage are to be realised, he concludes.

Comments