Caravans; Demise of Bulawayo’s pioneer mobile food outlets

Raymond Jaravaza, Showbiz Correspondent

MARIA Muleya could not understand the cause of the sudden hive of activity around her caravan — a modified food outlet on wheels — but all the excitement seemed to emanate from a discussion by her customers and a man she could not identify.

More men started to trickle in from different directions around her caravan and the man Muleya could not recognise, was the centre of attention.

The stranger seemed to be doing the talking while the group of men either nodded in agreement or threw a few questions at him here and there.

Muleya says she only got to learn about 30 minutes later that the man was a Highlanders Football Club legend Willard Mashinkila Khumalo, a local celebrity that her football loving customers could easily pick out from a large crowd in an instant.

“He was a bulky man with a friendly smile. My customers seemed to relate with him and although I didn’t know anything about him, I could, at least, tell that he was famous. Within a few minutes of his arrival with a friend at my caravan, more than 12 men had gathered around asking him all sorts of questions and he was taking his time to answer them one at a time.

“I later learnt his name was Willard Khumalo and that he used to play for Highlanders and was a very famous guy, especially to people that follow football,” Muleya told Saturday Leisure.

The incident, according to Muleya happened around 1998 when she was operating a food outlet on a caravan just outside Renkini Bus Terminus. Her caravan served food along the Sixth Avenue Extension, a major road that leads to western townships and joins into the ever-busy Luveve Road.

As a young mother-of-two, Muleya was still new in the cut-throat street food business that had muscled its way into a market dominated by established restaurants and cafeterias years before.

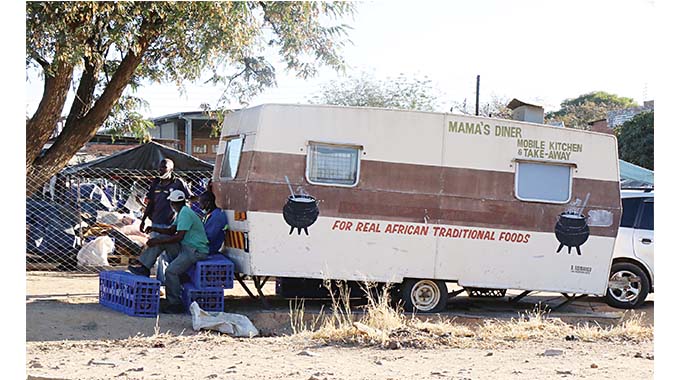

In the 90s when caravans started ‘invading’ Bulawayo streets, particularly in and around bus termini, in Kelvin and Belmont industrial areas, they were embraced as the go-to food outlets for the men and women on the go who wanted a quick bite during lunch, go back to work or catch a long distance bus.

The most common meals were hot cups of tea with sandwiches or amagwinya (fat cakes) for the early morning customers. Isitshwala with beef and vegetables was a hit for lunch and with time, enterprising caravan owners started spicing up their dishes to include ovals, inhloko (cow head meat) coupled with traditional dishes that included amacimbi (mopane worms).

Caravans suddenly became a hit with bus drivers, conductors and touts. For the men whose day started before the early morning buses’ engines were turned on to the last long distance buses trickling into Renkini Terminus before the sun disappeared into the horizon, caravans were the answer to their stomach’s needs.

Business boomed and competition got stiffer. More entrepreneurs bought the mobile food outlets and set base on every corner of the busy bus terminus.

“My uncle bought the caravan and asked me to get into a partnership with him. I cooked and he supplied the mealie meal and meat and soon, we had added breakfast to our menu. After a while, we served different dishes for lunch and the number of customers grew,” she said.

It’s often said that when one door closes, another one opens and for Muleya, the introduction of the loathed Economic Structural Adjustment Programme (Esap) — in the early 1990s drove her to go into self-employment.

Esap was a difficult period for thousands of workers in the 90s when the World Bank and International Monetary Fund initiated policy for Government to reduce expenditure by retrenching 25 percent of the civil service, withdrawing subsidies, commercialising and privatising state owned-owned companies.

Factory workers were not spared the brunt of Esap and were retrenched in droves. Thousands became unemployed in the blink of an eye.

“People were losing jobs every day, factories were closing and it was becoming extremely difficult to get a job so I had no choice but to find other means to survive and my uncle came up with the brilliant idea of selling food at Renkini,” narrated Muleya.

With workers deep in the throes of Esap, unemployment became the order of the day but life still had to go on for the breadwinners – albeit without steady wages.

“People started selling various items at Renkini from sandals made from old tyres, axes, hoes for cultivating in maize fields, cowbells and clothes so the terminus was always busy. Those people spent the whole day at Renkini and had to eat and that’s where we came in.

“There were a few established restaurants, but that didn’t deter us from operating our caravans, we beat the restaurants by selling our food cheaper and built a faithful client base over time,” she said.

Muleya estimates that Renkini had over 30 caravans at the peak of the business, but they all made money and fed their families.

A lot has changed since that chance encounter between caravan owner Muleya and footballer Khumalo. The ex-Highlanders player passed away in August 2015 and Muleya is now out of business.

“My two children went through school and college with money that I made from the caravan and so did the children of women that also operated their caravans at Renkini. Unfortunately, my first granddaughter who took over the business some years later couldn’t survive the 2008 hyper-inflation period and went out of business,” added Muleya.

Saturday Leisure took time to drive around Renkini Bus Terminus recently and counted less than eight caravans that still operate around the place.

Dorothy Mudiwa says business is low and the situation has been compounded by the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“As you can see Renkini is empty, there are no buses operating here anymore because of coronavirus and the people that come to hardwares, motor vehicle repair shops and N. Richards Wholesalers are the few customers that buy from us once in a while,” lamented Mudiwa.

In 2015, the Government ordered urban local authorities in the country to phase out caravan food traders citing health reasons. The move, however, sparked anxiety as it had the potential to render jobless, people who earned a living through operating the mobile food services.

Mudiwa believes the move at that time was instigated by restaurant and fast food outlet owners who complained that caravan operators were a threat to their businesses as they sold food at cheaper prices.

“People must make their own choice of where they want to buy food. We don’t have a problem with restaurants operating, even here at Renkini, but for them to try and influence government to shut us down was unfair,” Mudiwa said.

The many caravans that could be spotted in the Kelvin and Belmont Industrial areas have either been closed or moved. — @RaymondJaravaza.

Comments