Education for Liberation: Zim School in Zambia Part II

Pathisa Nyathi

The Zapu-Patriotic Front cadres manning the schools did see the glaring contradictions between material being used in schools and the hidden curriculum, particularly with regard to Mathematics and English Language text and other books.

A vigorous search was thus undertaken to identify and secure appropriate books at both primary and secondary school levels. Some text books in the Mozambican Ministry of Education for example “Historia de Africa” were being seriously considered.

An example of how the hidden curriculum worked became evident when the school’s Deputy Director, Paulos Matshaka entered a classroom and greeted the learners.

“Good morning, comrades,”

“Good morning, Sir,”

In response, Matshaka advised the learners that they were all comrades.

“We are all comrades in the school!”

“Good morning, comrades!”

“Good morning, comrade!” they all responded with thunderous applause. As Patrick Bolland observed, egalitarianism does not come naturally to those who have passed through the colonial mill.

For refugee schools without adequate financial support, self reliance was at the core of their thrust in learning. As a result, both self-discipline and self-reliance were given emphasis. An example at the JZ Moyo Boys’ School was the presence of a twenty-by twenty-foot area of open land cordoned off by five-foot high makeshift walls of woven grass, with a small opening in one wall for access. In addition to the practice of Agriculture, the boys were engaged in making wooden benches from unhewn limbs of trees.

Conventional desks were a rare commodity. A blackboard was made of a simple masonite, picked up from a building site in Lusaka, covered with any available dark-coloured paint. Grass walls reduced the decibel levels but also functioned to keep out dust. “As a visitor from Canada, I couldn’t help being impressed by the simultaneous use of three languages, Ndebele, Shona and English in all classes of the school.

For Zapu, the strategy was intended to break the barriers of tribalism. True, in former British colonies, teaching and learning were conducted in the English language medium. Tribalism, it was observed by Zapu-Patriotic Front, was used to foster the colonial strategy of divide-and-rule in the Southern Rhodesian colony. It was envisaged that through the use of trilingual approach, learners would go beyond mutual dependence and attain a new national consciousness in children.

Inflows into the school by refugees dictated that admissions be staggered. Arriving children joined a grade corresponding to the one they were in back in Rhodesia. When numbers got to forty-five or even as high as 150 in one class, a new section was formed. Children assisted late arrivals in coping with what they had learnt before the others arrived.

“I was surprised to discover that nearly 90% of the men teaching at JZ Camp were qualified teachers, while less than 10% of the women assigned to teaching duties in Victory Camp had received any formal training as teachers. This disparity reflects the lack of educational opportunities open to women inside Rhodesia-even in the “traditionally female” sector of education. But the assignment of Form 2 and Form 3 graduates to temporary teaching duties provided valuable experience for the women, before they would be given other duties; the Zapu Patriotic Front’s policy of keeping most of the qualified male teachers in the camp (rather than, for instance, transferring them to the liberation army) is yet another sign of the high priority of the educational programme within the organisation.”

What Bolland did not also appreciate with regard to a larger proportion of male qualified teachers was the manner in which males generally were targeted by the colonial settle regime soldiers. Males were targeted more than females as they were viewed as more prone to recruitment as guerrillas. Indeed, added to this was the bias exhibited by parents in sending boys to school ahead of their daughters.

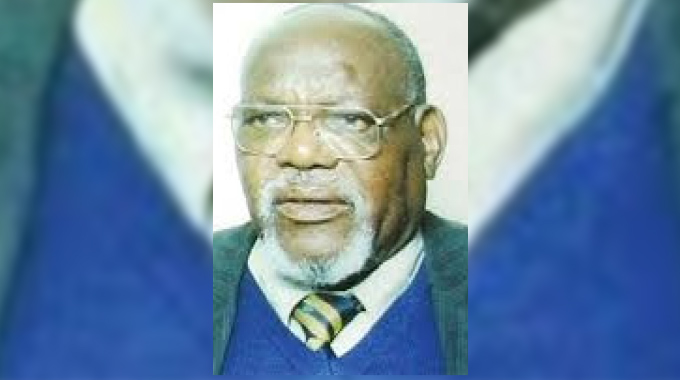

At this stage let’s buttress what Patrick Bolland observed at the Zimbabwe School by referring to the case of Petersen “Mjulumba” Ncube who was a teacher at the JZ Moyo School for boys. Ncube attended Seulah Primary School run by the Salvation Army Church. At the age of 12 he enrolled for Sub-Standard A in 1951. He later transferred to his home school, Mahetshe in 1953 where he remained till 1957. He proceeded to Tshelanyemba Central Primary School, also run by the Salvation Army Church. After expulsion from the school, he went to Manyane Primary School before proceeding to Hope Fountain Mission of the London Missionary Society (LMS) where he did a two-year teaching course (PTL).

After some teaching stint at Ntobe Primary School in Silobela, he went on to teach at Mbuya School, also a Salvation Army-run School in 1974 where he remained till 1977. The war of liberation was escalating at the time and Mr Ncube faced persecution from the Rhodesian police, forcing him to flee the country to join the struggle in Zambia. He, together with other qualified teachers, went to the Freedom Camp (FC) to do a two-week defensive military training programme. At the Nampundwe Transit camp, they had undergone the usual physical training and self-defence tactics and political education that everybody went through.

Mr Ncube then went to teach at the JZ Moyo Primary School for boys. The school was within a military camp under the command of Makanyanga. Paul Matshaka was the civilian head of the school. Matshaka (Nare/Nyathi of the Taueatsoala section of Nares) was among the teachers and pupils taken from the Lutheran Church-run Manama Secondary School in 1977. Dr Sikhanyiso Duke Ndlovu was the senior convener. Obert Matshalaga, also from Manama Secondary School, was in charge of scholarships.

When, in October 1978, the nearby Works Camp close to Victory Camp, was attacked during cross border raids by the Rhodesians, JZ Moyo School was forced to relocate to Solwezi further to the north, close to the border with the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Angola.

In 1980, Petersen and other teachers and pupils travelled back home to Rhodesia by buses and trains and were met at Luveve where a receiving camp had been set up for returnees. From there, he left for Mpopoma Township (Block 72) before setting off to where his younger brother Jack Mtsiwa Ncube lived in Luveve (Gwabalanda in the 40s section). After visiting the Ministry of Education offices, where he met AV Dube, he was allocated Kweneng Primary School in Bulilima-Mangwe District.

Comments