Life-changing wildlife revenue for rural Botswana community

Emmanuel Koro

Being resource-rich but almost endlessly poor.

This is the sad and most contradictory reality of the lives of many African rural communities living near the continent’s natural resource-rich national parks. But not so for Botswana’s Chobe Enclave rural community that is in the resource-rich wilderness area near the even more resource-rich Chobe National Park.

The Chobe Enclave Conservation Trust (CECT) is a community-based development agency that is credited for its promising efforts to take the Chobe Enclave Rural Community away from poverty. It has achieved this over the past 20 years through the careful management of funds generated from wildlife hunting, when hunting was still allowed in Botswana and lately through tourism projects such as bird-watching and lodge business partnerships.

One of the CECT’s flagship projects is the up-market (four-star) Ngoma Safari Lodge that it runs jointly and viably with a private sector partner, Albida Tourism under a renewable 20-year lease agreement. The CECT can take-over the Lodge when the lease period expires. So far, indications are that the Community is happy with the current partner.

While the Ngoma Safari Lodge is certainly generating good revenue for the Chobe Enclave Rural Community, they could be getting more income if sustainable hunting was part of their business model.

For many years before former President of Botswana Ian Khama’s sudden ban of wildlife hunting, including elephant hunting in 2013, most of the money that this rural community earned came from elephant hunting. The hunting revenue was used to finance the CECT office and community projects such as the milling project, poverty alleviation projects that include skills development to prepare villagers for employment and purchase of a tractor.

They also built a Parakarungu shop that they currently lease out to a private company. Among other important projects, they run a general dealer shop in Mabele Village and a grinding mill in Parakarungu Village. The CECT has a bank account and its finances are audited by a professional auditing company. The CECT office is run by 31 employees with an approved 2019 annual salary budget of P1.6 million.

Apart from benefiting from the Lodge lease fees, the Ngoma Safari Lodge employs 27 people from the community who can now provide for their family needs, unlike before when they were unemployed.

“The Ngoma Safari Lodge is an excellent investment by the Chobe Enclave Rural Community,” said one of the Ngoma Safari Lodge managers, Mr Peter Mukamba.

“Most of the people from our community working here were previously unemployed but now through employment they can send their children to school and build homes for their families. Their lives have improved a lot and they are happy. I am also very happy. Everything is going on well at Ngoma Safari Lodge.”

Ngoma Safari Lodge is a very important investment for the Chobe Enclave villagers who own the land on which it was built and also provided the labour to build it over two years until it was completed and became operational in 2011.

The four-star rated Ngoma Safari Lodge refreshingly overlooks the beautiful Chobe River and a nearby man-made waterhole where different types of wildlife can be clearly viewed. Employees say Ngoma Safari Lodge’s estimated value runs into several million pulas.

The lodge has eight thatched chalets that blend well with the natural environment, with each chalet housing two people, bringing the total capacity occupancy to 16 people.

Ngoma Safari Lodge

The lodge facilities include a bar, one plunge pool per chalet, open plan dining area. It also has a communal plunge pool. Each chalet has a shower both in and outside, including a jacuzzi inside. The Ngoma Safari Lodge boasts of four land cruisers for touring, two boats for boat cruises on Chobe River and two minibuses to pick up guests from the Kasane International Airport where packed planes with tourists from different parts of the world land daily.

Missed opportunity to earn more revenue

Missing from the opportunities to raise more revenue for the Chobe Enclave Rural Community is the number one income earner in most rural communities of Southern Africa settled near national parks – wildlife-hunting revenue. This followed what rural residents here collectively described as a disappointing and sudden ban of all types of wildlife hunting in 2013 by their former, President Ian Khama.

Meanwhile, a retired Botswana-based safari operator who has been involved with hunting and photographic safari businesses for the past 40 years, Mr Mark Kyriacou said he felt sorry that the ban on all types of hunting made a lot of poor rural residents suffer immensely.

“The ban has hurt poor people,” said Mr Kyriacou.

“I don’t have a problem that Ian Khama dislikes hunting. That is his view. But the point is that he (Ian Khama) is not the people of Botswana. He was the President of Botswana when he made the ban and he was put there by the people of Botswana. Therefore he must have done what the people want. The people of Botswana want to continue hunting.”

Mr Kyriacou said Mr Khama did not only ban elephant hunting, as everyone seems to think. He banned hunting of all wildlife on all public land in Botswana.

“The problem is not how the private safari operators were affected,” argues Mr Kyriacou.

“The problem is how the poor people of Botswana were affected. Not safari operators. They are people like me who have already made money. The problem is that poor people from the villages are no longer surviving on hunting benefits. They are no longer getting protein-rich meat from hunting and have lost their jobs.”

Mr Kyriacou said the wildlife-hunting ban had resulted in an increase in wildlife populations such as lions and elephants. This has in turn increased human wildlife conflict in rural Botswana.

He noted with concern that when leopards and hyenas kill people’s goats and lions kill their cattle, the villagers resort to poisoning them in defence of their livestock and socio-economic wellbeing. In the long term, such continuous revenge or defensive wildlife kills would hurt the non-consumptive tourism industry that earns Botswana handsome tourism revenue annually.

“The people have told the Government and their ministers that these are your animals,” said Mr Kyriacou. “You must come and take them away if we cannot use them. If you don’t take them away we will kill them.”

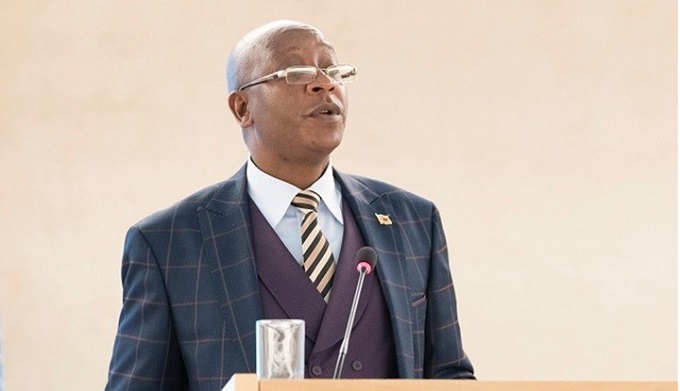

There is now increasing hope that not only the Chobe Enclave Rural Community but other Botswana rural communities could soon earn more revenue through wildlife hunting. This follows the recent signal from President Mogkweetsi Masisi to resume wildlife hunting anytime in the future in Botswana, probably this year.

“My reaction to President Masisi is very favourable,” said Mr Kyriacou. “It’s the best thing he can do (lift the ban on hunting). He must do it carefully, making sure that the benefits go to the communities and not the people who come to take advantage of hunting.”

– Emmanuel Koro is a Johannesburg-based international award-winning environmental journalist who has written extensively on environment and development issues in Africa.

Comments