Long silence awaits banned Heath Streak and cricket’s condemned corruptors

June 2015, and I’m in the headmaster’s study at Christchurch boys’ high school, listening to him tick off the famous New Zealand sportsmen who went there.

Dan Carter, Brodie Retallick, Andrew Mehrtens, Owen Franks, Aaron Mauger, Steve Hansen, Graham Henry. He was running out of fingers, and he hadn’t even started on the cricketers – Richard Hadlee, Chris Martin, Tom Latham, Corey Anderson. “And the other one, of course, one of the most famous,” he paused, “only, we don’t talk about him too much any more around here.” He paused again. Eventually his colleague cut in: “Chris Cairns.”

The way I remember it, there was a lot left unsaid in that long, awkward silence. Anger, scorn, even a little embarrassment. He was a proud man, running a proud school.

Cairns was never actually convicted of fixing. He was acquitted on charges of perjury and perverting the course of justice. But he was condemned by the testimony of his teammates Lou Vincent and Brendon McCullum. After such knowledge, what forgiveness? A lot of the men who have been caught find their way back into the game. Mohammad Amir is still playing, surly, sorry for himself. He has retired from international cricket. Mohammad Asif has been playing club matches in Norway and the United States. Salman Butt works as a pundit in Pakistan. Danish Kaneria is playing veteran’s Twenty20. Mohammad Ashraful is back playing first-class cricket.

Vincent himself is running a backyard club for local kids in Waikato, using his old kit. He still hopes that he can persuade the authorities to overturn his lifetime ban. What else do you do, when your betrayal means they take away the game you gave your life to? Cairns, though, has spent the years since living in Canberra: “I’m completely scorched, burnt completely.” He keeps a low profile, little asked about, less said, apart from the occasional interview about his new business filming sportspeople perform in front of virtual crowds on a green screen.

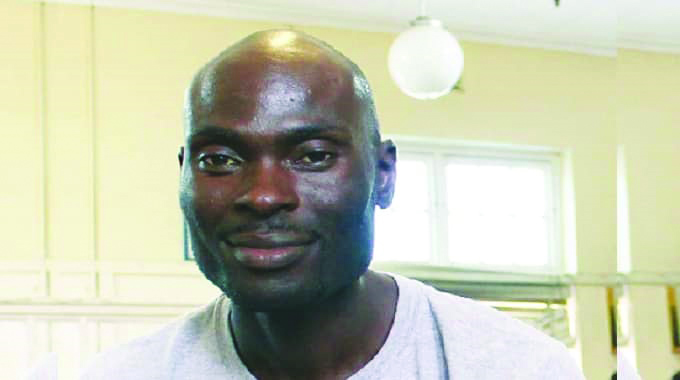

Two weeks ago, the International Cricket Council announced that Heath Streak had been banned from cricket for eight years. The former Zimbabwe Test captain had been caught working as a middleman for a fixer. There have been a lot of these cases in the past few weeks, as the ICC’s anti-corruption unit settles a spate of investigations from two years or so ago. On Wednesday, it announced that Nuwan Zoysa, who played 30 Tests for Sri Lanka, has been banned for six years.

Streak’s case felt the most shocking. Like Cairns, he was a heroic cricketer, an all-action all-rounder, still the only man to take 200 Test wickets for Zimbabwe, and the star turn in their great team of the late 1990s, a fast bowler with a bustling, open-chested action who took on England almost single-handed in 2000. His six for 87 at Lord’s won him a place on one of the banners hanging around the back of the stands because they were the best bowling figures by a Zimbabwean at the ground. He was also one of the few players from that generation who stuck with the team when things started to fall apart, first as captain, and then as coach.

“Heath was well respected and liked by lots of people in the game,” says Alex Marshall, who runs the anti-corruption unit. “He’s someone who’d stayed in the country when a lot of others left, and who stood up for cricket in Zimbabwe. I’ve met him several times, I’ve been to Bulawayo to interview him, and I’ve no doubt at all that he cares about cricket in Zimbabwe, he’s not a cynic who doesn’t care about cricket. He does.”

One of the ironies of the case is that the fixers used that care against him. When they first approached him, it was to ask for his help with a plan to set up a new T20 tournament in Zimbabwe. “There have been several similar proposals in Zimbabwe and other countries,” Marshall adds.

“You can see the lure of the offer, you’re sitting there in a cash-strapped ICC member, and someone comes along and says: ‘You’re going to make half a million dollars as a board and there’s going to be loads of cricket played in this great new televised tournament.’ They always say: ‘This will help develop and promote cricket in your country, it will give more youngsters a chance to get involved.’ So they sell it as being for the benefit for cricket, to help with growth and development. And, of course, they also say: ‘There’s going to be money on the table for you as well.’”

Streak liked money and needed it for the game reserve his family run outside Bulawayo. He’d had trouble getting what he was owed from Zimbabwe Cricket. In the end, the bookies gave him two bitcoins, which he converted into $35,000 and a new mobile phone. A hard-won reputation, sold cheap.

Marshall says: “The problem with his offence is that because people trusted him and liked him, that allowed him [the corruptor] to get access to other players, he helped these corruptors approach other players, he even gave him references, and that’s the bit that’s hardest for him, I think. The good news is we are now much clearer who these corruptors are, how many of them there are and how they work.”

The ACU is bringing in new regulations to help fight them, too. “We had one yesterday, a very serious corruptor, who basically told us: ‘I’m going to try and do my job, you’re going trying to do your job, so try and catch me if you can.’ OK, we will.”

The game goes on. But not for Streak. After all these years, like Cairns, he will find the long silence has settled over him and his career. – The Guardian

Comments