Removing Rhodes’ grave won’t change history

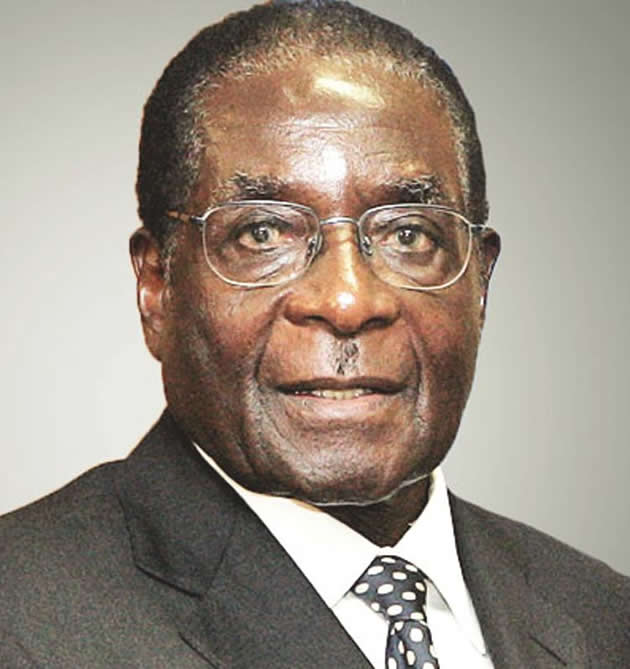

Saul Gwakuba Ndlovu

SOME Zimbabwean print media recently published stories to the effect that some members of the Zanu-PF Youth League were stopped by an arm of the national security machinery from removing the remains of Cecil John Rhodes from his grave on the Matopo Hills and sending them to Britain or throwing them into the Zambezi River.

The national security machinery personnel advised the Zanu-PF youths at the party’s Bulawayo provincial offices that exhuming Rhodes’ bones and doing whatever with them would damage Zimbabwe’s public image and harm the tourism industry a great deal.

The suggestion to remove Rhodes’ remains from the Matopo Hills and ship them to his home country was made a few years ago but was strongly discouraged by some senior government officials as well as by popular public sentiment.

The author of this opinion article was among those who opposed the suggestion without reservation. Rhodes died in Cape Town in June 1902, two months short of 113 years ago.

He and a couple of his colonial colleagues were buried in a huge rock on one of the scenic Matopo Hills. The particular hill is called “Malinda Ndzimu” tjiKalanga for “keepers of god”

The hill enables tourists to have an extremely wide panoramic view of the western horizon of that sector of the Matopo Hills. Below “Malinda Ndzimu” lies a beautiful stretch of fertile land on which is located the Matopo Research Station and the Rhodes Elementary Preparatory School. (REPS).

Rhodes’ life passion was to turn not only Africa but much of the other parts of the world into British colonial possessions. He managed to grab what is now Zimbabwe, a very large part of Zambia, and was instrumental in getting Nyasaland, now Malawi, to become a British protectorate.

Barotseland, now Zambia’s Western Province, also became a British protectorate because of its fear of Rhodes encroaching colonial schemes, among other factors.

What is now Zimbabwe was named “Rhodesia” in 1894 by Rhodes’ senior officials heading his company, the British South Africa Chartered Company (BSACC). The word “chartered” is usually left out.

Several British statesmen such as Queen Victoria’s son-in-law, Lord Fife, and top British government colonial official, Lord Selbourne, were BSAC directors. Several others, such as Lord Salisbury, one time British Prime Minister were shareholders in Rhodes’ enterprises such as the diamond undertakings.

He was indeed a corrupt colonialist, and died saying: “So much to do, so little done.”

He bequeathed his land estates, one at Nyanga and the other at Matopo, to the government of Southern Rhodesia, and, thus, by succession, to that of Zimbabwe. He also established a commonwealth scholarship that has benefited a large number of people of different races among whom was the late Lee Kuan Yew of Singapore. He was that country’s founding Prime Minister in 1965.

Rhodes was not married and died childless. He was buried in Southern Rhodesia, a country he had colonised by hook or crook. Incidentally, Rhodes left Britain initially for Natal in South Africa for purely health reasons. Natal was at that time a British colony, so was the Cape territory, known then as the Cape Colony.

He later became Prime Minister of that colony, that is, the Cape Colony, and it was during that time that he colonised our land which was later named “Rhodesia” in his honour. The “Southern” was prefixed a few years later when it became obvious that the land just across the Zambezi River would also became BSAC territory.

That additional BSAC possession was called “Northern” Rhodesia to differentiate it from the one on the Zambezi River’s Southern side. The BSAC’s former territories are now Zimbabwe and Zambia respectively.

One of Rhodes’ most ardent dreams was to build a railway line that would link Cape Town in the southernmost part of the African continent with Cairo to the north in Egypt. That was done but only as far as Bulawayo in 1897, some five years before he died.

We should not forget that he got the Harare-Beira railway in place shortly after completing the Mafeking-Bulawayo line.

Rhodes was an incorrigible colonialist who thought the world belonged to Britain. To him, no nation was more eligible to rule this world than Britain. As for us black people, to him we were mere ignorant and naked barbarians.

As far as Rhodes was concerned, the best people to rule the world were the English, or if not, the Anglo-Saxon as a race. Other races were not good enough and that was why he was almost always at logger heads with Jan Hoffmeyr the highly respected intellectual power behind the formation of the quasi- secret Afrikaaner organisation, the Broederbond.

To Rhodes, blacks were created to be despised, to be punished and to be pushed by law and force of arms from healthy fertile regions to inhospitable areas, hence his law, the Glen Grey Act, which forced whole African communities from the Glen Grey District and Fingoland of the then Cape colony to much less favourable areas. That Act was the Land Apportionment Act’s basis.

That he hated us is a historical fact. But should we revenge? If so, should we revenge against his bleached bones some 113 years after his death? How can we explain, let alone justify, revenging against a dead person? What about the Zimbabwean government’s policy of national reconciliation? In our culture, a dead person is buried by as large a number of people as can turn up, even by his worst enemies and most virulent critics.

Why is that so? Because “wafa wanaka” this is a part of the “Ubuntu, bunhu, hunhu culture.

Were Rhodes as alive in 1980 as Ian Smith was, the government would most likely have treated him exactly the same way as it treated Ian Smith. Why? Because of the national policy of reconciliation.

So from a purely political point of view, it does not make any sense to be hostile to 113-year-old relics of Rhodes, but to have accepted his successor, Ian Smith, as one of us in an independent Zimbabwe.

We have schools called by the name of Rhodes, that of one of his senior military commanders, Major Allan Wilson, as well as by the name of the first white settler prime minister of this country, Coghlan, who lies buried in a grave next to that of Rhodes on the “Malinda Ndzimu” hill.

Should we also call for the destruction of those schools or for a change of their respective names?

There is something we should learn about history, and it is that it can neither be falsified, nor erased from the people’s memories.

If we falsify it, what we put in its place becomes incredible because it lacks both spatial and chronological authenticity. That means, simply stated, that those who made our history were at particular places at specific times or periods.

When dealing with the story about Zimbabwe, we have to admit and highlight that from 1888, Rhodes and his cohorts played a major role in shaping this country’s political development for the next two years. Thereafter, they played a very big role in the country’s socio-economic future until 1980 when it attained independence.

Of course, they were imperialist invaders, a fact that led to us to take up arms to free the country from them. While they were in power, they lived, died and were buried here.

Some of them were more or less immortalised in the form of monuments such as statues. All these monuments and other relics comprise a historical heritage of an independent Zimbabwe.

Those relics contribute a great deal to the wealth of the historical culture of our country. When we talk about Zimbabwe’s military history, we cannot avoid mentioning how the Allan Wilson patrol was routed by Mtshana Khumalo’s forces just across the Shangani River as they (Wilson’s Patrol) tried to track down King Lobhengula as he fled northwards from the army of Cecil John Rhodes.

A serious student of Zimbabwe’s military history and culture will not fail to include in his or her notes a number of names such as Mgandane, Major Plumer, Sekuru Kaguvi, Mbuya Nehanda, Lieutenant Dan Judson, Captain Randolph C. Nesbitt, Chief Sikombo Mguni, Chief Mashayamombe, Chief Makoni, Brigadier Gordon, John Dube, Josiah Tongogara and many others.

That of the country’s military — political history will just have to describe the role of the various Munhumutapas, the Mambos, Mzilikazi, Lobhengula, Rhodes and his colonial successors right up to Ian Smith, Bishop Muzorewa, the various national patriots, beginning with those who were against the Rudd Concession right up to Robert Mugabe and Joshua Nkomo; that means, in effect, from the era of Portuguese encroachment right up to the Lancaster House Conference of December 1979.

That massive period is extremely full of political, economic, military, cultural and social historical information about Zimbabwe and the concerned student would have to visit Great Zimbabwe, Matopo Hills, and end up at the National Heroes Acre.

Saul Gwakuba Ndlovu is a retired, Bulawayo-based journalist. He can be contacted on cell 0734 328 136 or through e-mail. [email protected].

Comments