Siltation blocks irrigation development

Hazel Marimbiza

For decades, Mrs Elizabeth Chimuti, a small-scale farmer in Mashonaland East, relied on the water that flowed from Murara Dam into dug-out trenches to irrigate her maize.

But when some two years ago the dam dried up due to poor rainfall and siltation, the impact on the 57-year-old and the other smallholder women farmers at Murara Irrigation Scheme was severe.

“The temperatures were so high that some of our crops could not survive,” said Mrs Chimuti, a widowed mother of two who now lives with her two grandchildren.

“It is not only us humans that suffered but (even) our livestock as drinking water dried and grazing lands got depleted.”

Mutoko is very dry because of inconsistent rains during each year’s rainy season, August through February, over the past 20 years.

Murara Irrigation Scheme, a small community farm which is located in Chimoyo communal area, about 30 km east of Mutoko town is in a low rainfall area, which receives about 400 millimetres of rainfall per year on average. The rainfall is not adequate for meaningful crop production, making irrigation a critical investment in the area.

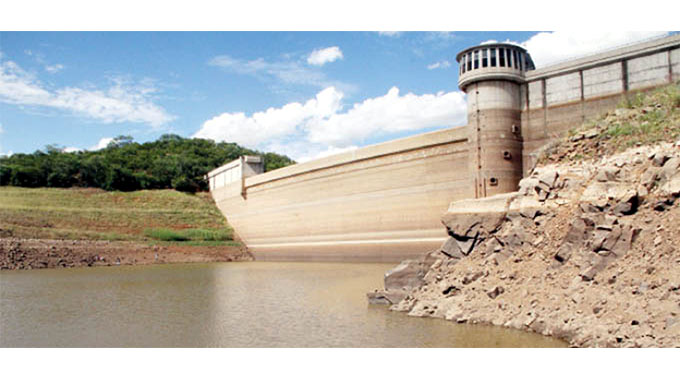

The scheme is 18 hectares in extent with 36 plot holders, each holding 0.5 hectares. It comprises members from the same village. The scheme used to draw water from Murara Dam, which was constructed in 1975.

The irrigation scheme used to perform well but now siltation threatens its viability.

In general terms, siltation refers to the increased concentration of suspended sediments, and to the increased accumulation of fine sediments on bottoms where they are undesirable, especially fine sand or clay.

Other farmers upstream of the dam, which provides the water for the irrigation network, have for years cultivated the river banks, resulting in erosion and increasing blockages of irrigation canals with sand and soil washed downstream.

With the dam below capacity and climate change increasingly bringing unfavorable farming conditions, there have been growing concerns from female farmers in Murara community over the state of affairs in water bodies and there are growing calls for Government and development partners to assist them in de-silting major water bodies.

Mrs Tendai Hungwe a villager in the area said: “We have a problem of limited irrigation water throughout the year at Murara. This is due to the high level of siltation at our local dam.

“The dam is a source of livelihood for people in this ward, but due to the current state of affairs, it can’t hold any substantial amount of water.

“Our appeal is for Government or its partners to help us in de-silting the dam. Its water carrying capacity is diminishing with each farming season.”

Mrs Hungwe said besides supplying water to Murara project, the water body was also critical for livestock production in the area.

She said the dam was also providing water for domestic use and many other villagers who were into horticulture.

Another villager, Ms Pauline Banda said rivers and dams were critical components for irrigation development and livestock production.

“We are very worried with diminishing of water sources in our area,” she said.

“You will realise that we get water from either rivers or dams and most of these are now heavily silted. They no longer hold water throughout the year. Our appeal is for Government and development agencies to join hands with communities in addressing siltation challenges.

“In some cases, we need to de-silt the dams and increase their water holding capacity.”

Ms Banda said it was important for the community to be proactive in addressing siltation issues.

Head of Communications at Disaster and Environmental Management Trust, Mr Romeo Chingezi said the siltation of Murara Dam was affecting future expansion of the project.

“Farmers here need more water for irrigation so that we may extend their project to accommodate more plot holders,” he said.

“At the moment they have few people, but with more water we can increase productivity.”

Mr Chingezi said irrigation development would go a long way in uplifting the economies of most households headed by women.

“Murara livelihoods are hinged on livestock production and when it comes to irrigation farming, you will note that most plot holders at these schemes are women,” he said.

“If they have fully functional projects, we can address some of the social problems in our communities.

“However, the greatest threat to irrigation farming is the siltation of dams and drying up of some boreholes.”

While weather-related disasters strike rich and poor countries alike, they are often most crippling for smaller and lower-income countries that are least able to cope. Among the most vulnerable are Zimbabwe’s poorest communities. The social and economic impacts of these climate shocks can have severe consequences for development.

National figures on the loss of capacity in Zimbabwe’s dozens of large reservoirs and thousands of smaller ones are scarce.

Environmentalist Mr Happison Chikova estimates that nationwide, 108 rural reservoirs have been lost to a combination of siltation and drought over the past 20 years.

Smallholder irrigation in Zimbabwe has numerous challenges, with more failures than successes being reported. The underperformance of smallholder irrigation schemes is largely a result of unreliable and inadequate water delivery.

Globally, smallholder irrigation systems are viewed as critical common property resources that are needed to increase crop water supply and sustain livelihoods in semi-arid regions.

Thus, improving agriculture and enhancing productivity through small-holder irrigation is one of the key strategies for alleviating poverty and improving the livelihoods of women in rural communities because the majority of the poor depend directly or indirectly on agriculture.

This is particularly true for Zimbabwe, where approximately 80% of agricultural land lies in arid or semi-arid regions.

Policies that govern water supply need to be improved, coupled with education of irrigators and a pluralistic extension system. All these are needed if the productivity of smallholder irrigation schemes is to be improved.

A new World Bank Group paper on climate change and water resources planning, development and management in Zimbabwe projects that by 2050 there will be significant reduction is rainfall, river flows and groundwater recharge, with the highest impacts on the driest water catchments of southern Zimbabwe.

The report therefore urges policymakers to develop an integrated climate change strategy for those sectors most affected by climate change: water and agriculture. It also recommends rehabilitating and expanding water supply and water resources infrastructure, focusing greater attention to the management and development of groundwater as well as improving water use efficiency, encouraging conservation and water recycling, and improving design standards to build resilience into infrastructure such as dams, levees and bridges, among other steps.

The director of the Zimbabwe National Environmental Trust, Mr Joseph Tasosa believes part of the solution is to change cultivation methods.

“At times people practise stream-bank cultivation, and when it rains those cultivated areas are washed straight into the water. As time goes by, this soil fills the water basins, and in the end the reservoirs are filled with silt. Farmers should desist from stream bank cultivation to avoid siltation of dams,” said Mr Tasosa.

Comments