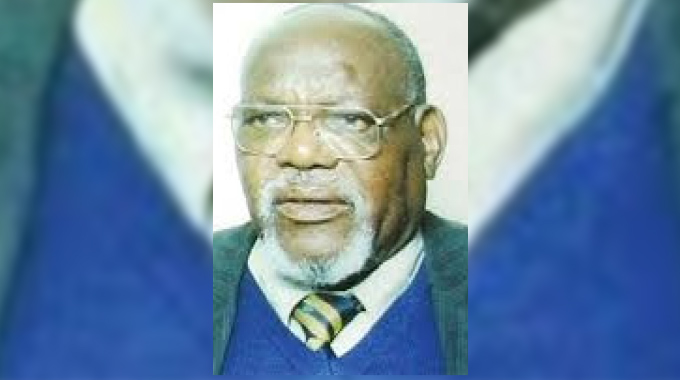

The ‘curse’ of loving a liberator – Sikhanyiso ‘Duke’ Ndlovu’s widow speaks

Yoliswa Dube-Moyo

WHEN the Rhodesian police slammed open the door to the late national hero, Cde Sikhanyiso “Duke” Ndlovu’s home in the thick of the night to read orders of his arrest back in 1964, his wife, Dr Rose Ndlovu, was left staggered.

With a two-year-old son, Mandla, in her care, the then 25-year-old Dr Ndlovu could not help but ask the question, what next?

In dramatic fashion, the Rhodesian police had taken away her husband in the back of a van and headed to prison before transporting him to Gonakudzingwa Restriction Camp days later.

Like many wives to political activists who fought hard to see black majority rule in the country, Dr Ndlovu had to quickly pick herself up and become the driving force needed to keep her family going.

“My husband was always involved in politics. In 1962, he was a member of Zapu. He was involved in youth activities and so on. You know then, all these things were not public, they were done underground. You wouldn’t go around saying we’re doing this and that in politics. His activism got him arrested and detained at Gonakudzingwa Restriction Camp in 1964. We didn’t even know there was such a place. It was somewhere along the border between Rhodesia and Mozambique,” said the soft spoken Dr Ndlovu.

Life got difficult for her as her husband was to live in restriction for the nine months that followed.

“At that point, we still had one child. Being left at home alone with Mandla was difficult. I didn’t drive then and I was working at Mpilo (Central Hospital). Transport was not easily available. To get to Mpilo, you had to first get a bus into town and then a bus from town to Mpilo, so that was very difficult. My in-laws helped with somebody to come and stay with me. It was quite scary, I was young and had a small child to look after,” she said.

Dr Ndlovu said she wasn’t particularly scared of being detained herself or further intimidation from the white settlers.

“It wasn’t that. It was being alone and uncertain as to what next. It was scary because when these people (whites) came, it was at night. They would just slam the door open. There were the police, the van outside and then they read ‘Sikhanyiso Ndlovu, you’re now going to be restricted to Gonakudzingwa for such and such a period…’ They would then take the person and leave. You would then think, what next. What’s going to happen?”

She continued: “That Gonakudzingwa was not an easy place to get to. I remember I had to ask other people for help. There was a Mrs Musongelwa, her husband had been detained there at some point. I had to ask from them how to get there. The night he (Cde Ndlovu) was taken, they first went with him to prison; they didn’t head out that night. In the morning, I asked somebody to accompany me and so we went to the prison. They said you better take some food because there’s not enough food at the prison.”

Dr Ndlovu said she had to cook some food to take to her husband in prison.

“It wasn’t an open prison. I think you talked through the window. From there, they were taken to Gonakudzingwa after a couple of days or so. He (Cde Ndlovu) was detained for around nine months before he came back home,” she said.

Not only was one required to be a mother and explain to the children the absence of their father, but they also had to be a good wife who is supportive of their spouse in difficult circumstances in order to keep the marriage going.

“We did go and visit him once by train. There was a train that would be travelling to Mozambique but it stopped at some place which was known as the stop for Gonakudzingwa. So, I took the child with me. Some of the wives of the other detainees gave me information and we travelled to this Gonakudzingwa wilderness. It was quite a wilderness place. You didn’t know what to expect. We were there for a couple of days because I wasn’t on leave or anything. I mean, you couldn’t ask for leave from government services in those days and say I’m going to see my husband who’s restricted. You just had to take off days because that (openly going to Gonakudzingwa) wouldn’t put you in good books with the authorities. You know, if the authorities were aware that you were the wife of a politician, you were not really in good books. You wouldn’t expect any help or support that’s why you wouldn’t even say, ah, I’m going to Gonakudzingwa to see my husband. You just did it very quietly,” she said.

Having met back in Durban, South Africa in 1960, Rose and Sikhanyiso got married in September of 1961.

“That’s where I was going to nursing school. He was working in Durban but not at the same place I was. We got married in September 1961, I had just completed my nursing programme. We came to Bulawayo in 1962; I was a qualified registered nurse then. I worked at Mpilo Central Hospital and he worked for the Bulawayo City Council as a social worker. We had our first child, Mandla in 1962. He’s late now,” said Dr Ndlovu.

During those days, she said, blacks and whites working in the same profession got different salaries.

“There were salaries for whites and salaries for blacks. So even with nurses, there were two grades of salaries. The white nurses were on a different scale and the black nurses were on a lower scale even though they were all registered nurses,” said Dr Ndlovu.

Colonial Rhodesia was punctuated by brutalities against blacks and harsh segregation and repressive laws. Among them was the separation of salaries according to race.

Because of the need to allow a black vote during the general election of 1962, some black workers got a salary increase as blacks were only allowed to vote if they were at a certain salary scale.

“I think it was towards the end of 1962 when they were trying to create this middle class of blacks so that they could vote. Remember blacks were not even voting at that time but there were a few blacks on a certain salary scale who could vote. So, I think to increase the number of blacks that could vote, they decided to put all registered nurses and other professions on the white scale salaries. So our salaries zoomed up within a few months. The nurses were some of the few who were upgraded because I remember teachers were still on a low scale,” said Dr Ndlovu.

“The working conditions were different in the sense that certain positions, for instance, Senior Sisters or Matron positions could only be given to whites. There were no black Matrons; there were just junior nurses.”

Rhodesia was established under the sponsorship of Cecil John Rhodes and his British South Africa Company.

He firmly believed in the White-Man’s Burden idea of the duty of the Anglo-Saxon race to help “civilise” the “darker” corners of the world and regarded British imperialism as a positive force for this purpose.

The settlers who occupied colonial Zimbabwe shared this view of the world and treated the indigenous black population as children who needed their guidance, protection, and civilisation.

Racial segregation permeated the entire colonial project at every level, whether it was in sports, hotel facilities, or the use of public conveniences and amenities.

White racism in colonial Zimbabwe was also informed by a sense of fear, given the fact that whites were grossly outnumbered in the country throughout the colonial period and were always afraid of being overwhelmed by the black majority. This contributed to their determination to control the blacks and “keep them in their place”.

“You know Mpilo (Central Hospital) was for blacks, United Bulawayo Hospitals was for whites and Richard Morris was for coloureds. Something like that.

“So, blacks couldn’t work at UBH but the whites were able to work at any of the hospitals. This meant that if Mpilo was for blacks and UBH was for the whites, the two hospitals were not equally equipped. The white hospitals always seemed to have more resources than those for blacks,” said Dr Ndlovu.

Meanwhile, after spending nine months at Gonakudzingwa Restriction Camp, Cde Ndlovu lost his job at the Bulawayo City Council.

“It was an uneasy time. He had been looking for a scholarship to go overseas to study. I don’t know how he got in touch with people who linked him to an organisation that gave blacks scholarships to study in America. He made an application and got back a letter saying he had to get himself to Zambia and then arrangements for his travel to the US would be made from there. That’s how he left Rhodesia,” said Dr Ndlovu.

She continued: “I was still working at Mpilo. I had actually just completed a midwifery course. I wasn’t even officially a citizen at that time. You could apply for citizenship after staying in Rhodesia for two years I think. First, I took citizenship and I had to apply for a passport. By then, my son was still very young so he was added onto my passport. I think I got my passport just before Ian Smith declared UDI. We then travelled to join my husband in the States. I was later able to get temporary registration to work as a registered nurse in the USA. It was for one year but it helped for me to get the visa to be able to go.”

Dr Ndlovu and Cde Ndlovu were in the United States of America until 1978.

“We came down to Zambia at the height of the liberation struggle in 1978. You know there were all those talks in-between. Zapu had a big office in Zambia; that’s where (late Vice President Dr) Joshua Nkomo and many of the other leaders were. There were many people at the camps in Zambia; Victory, Freedom, Mkushi. My husband would go to the camps to help. He actually set up a secretarial school so that the young people at the camps could take some courses. Even when he was restricted to Gonakudzingwa, he started a school there because there were a lot of young people who had left school early,” said Dr Ndlovu.

After Independence, Cde Ndlovu established the Zimbabwe Distance Education College.

“At that time in the 1980s, very few people here knew about distance education. In fact, people used to ask what distance education was and some even used to call it long distance education because the concept was quite new,” said Dr Ndlovu.

As an educator, Cde Ndlovu was also involved in army education and was chairperson of army schools.

Cde Ndlovu rose through the ranks and was appointed to the Zanu-PF Politburo.

He served as the Deputy Minister of Education from 1995 to 2000.

Cde Ndlovu was appointed Minister of Information by former President Mr Robert Mugabe in 2007.

Rose and Sikhanyiso had been married for 54 years at the time of his death. – @Yolisswa

Comments