The unplanned settlements’ negative impact on development

Roselyne Sachiti

RURAL African societies since pre-colonialism have dominated the African scape but as the winds of change sailed through Africa and the resultant economic development, a strain developed bearing pressure on already designated land.

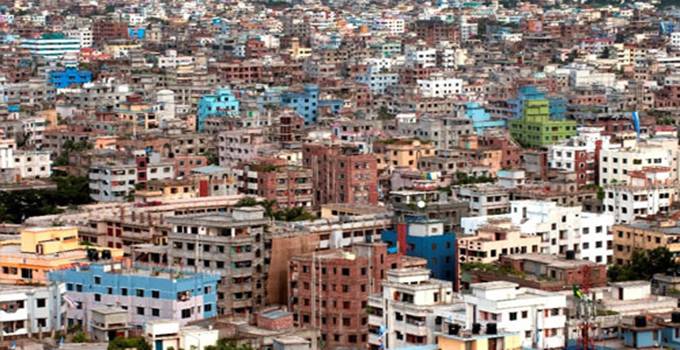

The emerging independent countries experienced a rapid reorientation of their social and economic lives that caused attraction towards cities leading to urbanism and new challenges in the form of unplanned and haphazard settlements that lack basic amenities like water, sewer and road infrastructure. Examples of these in context are Epworth and Hopley in Harare, Zimbabwe, Khayelitsha in Cape Town South Africa, and Maitu in Nairobi Kenya.

According to UNCHS a slum is “a term used to describe a wide range of low-income settlements and/or poor human living conditions”. The definition also covers housing areas that were once respectable or even desirable, but which have since deteriorated, as the original owners have moved to new or better areas of the cities (an example to this seemingly complex definition is here in Zimbabwe, the area between Harare’s Luck Street and Kaguvi Street which is now dominated by unruly gangs who have settled in this part of downtown.) The term slum, has, however come to include also the vast informal settlements that are quickly becoming the most visual expression of urban poverty.

One example is Hopley on the southern outskirts of Harare. The quality of dwellings in such settlements varies from the simple shack to permanent structures, while access to water, electricity, sanitation and other basic services and infrastructure tends to be limited.

According to UNHABITAT, Zimbabwe’s urbanisation rate has increased from 10.64 percent in 1950 to 38.25 percent in 2010 and is expected to increase to 64.35 percent by 2050.

Development challenges

The increase in teenage marriages in urban slum settlements has been attributed to housing challenges. A 2003 report by The United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UNCHS) states that “the legal acquisition of land is far beyond the means of most people, as buildable land is in short supply; opportunities for employment are very limited and the rate of population increase is high, thereby compounding the problematic housing situation”. Housing is inadequate in urban slum settlements and being areas with high teen fertility young girls normally tend to gravitate towards an ‘escape route’ from the squalid conditions within the family home’ by getting married or cohabiting with her partner in a different setting. The catastrophe is that this perpetuates a vicious cycle where more and more slum settlements are born to cater for the increasing family units. It perpetuates poverty, lack of economic opportunities and places pressure on an already strained ecosystem.

One of the practical policy issues is to offer low cost housing models. In Zimbabwe there have been attempts to finance and offer low cost housing.

Government promised to build 1,5 million houses between 2018 and 2023.

It is an accepted fact also that more migrants move into Harare more than into any other city in Zimbabwe. In order to cope with the fast rising population in Harare, it has been estimated that about 100 000 additional residential units are required each year. However, there is evidence that because of economic hardships, nothing near this target is being built each year, either by government and its housing agencies or by private/public sector participation. The immediate consequence of this is that in many parts of Harare, especially where the poor and low-income people live, there is congestion, inadequate infrastructural facilities for the ever-increasing demands place on them, inadequate provision of water supply, power and poor methods of waste disposal. The catastrophe is that there is a strain on social service.

Sometime last year, it was revealed that Harare City Council clinics were failing to serve the ever burgeoning population in Epworth. This is because the closest clinic in Hatfield was designed for a smaller population.

Such inadequacies place a tremendous impact on the production of housing. Sometimes it has led to demolition, eviction, inaccessibility, substandard houses and many are outright uninhabitable.

Examples of this are Operation Murambatsvina conducted in 2005 or efforts to evict slum settlements by City of Harare in August last year under Operation Restore Order.

In the past government had control of urban development through the Urban Development Corporation (UDCORP) but the post ESAP era saw liberalization of the housing delivery system. However, the intentions in as much as they were noble resulted in the current catastrophes faced by Zimbabwe because liberalization meant commercialisation and priced low income earners out of the market for housing. An example is how a well-constructed suburb like the CABS Budiriro 5 housing scheme is failing to find any takers. Ironically CABS even partnered City of Harare for the project yet it has no gravity in the market. Four years ago, Government took away the management of land development and administration from housing cooperatives and conferred the work on the shoulders of Udcorp, after noting that the housing cooperatives were ripping off unsuspecting home-seekers through double allocations and failure to restore order.

The other problem with urban slum settlements is in the form of high crime rates.

A report published by UN-HABITAT’s new Global Report on Human Settlements in 2003 states that: The world’s slums are growing, and growing, with the number of people living in such dire conditions now at the 1 billion mark – making up 32 percent of the global urban population.

In developing regions, slum dwellers account for 43 percent of the population in contrast to about 6 percent in more developed regions. In sub-Saharan Africa, the proportion of urban residents in slums is highest at 71.9 percent.’

This places law enforcement efforts under a huge strain and undermines efforts to offer citizens protection because of the haphazard and undocumented nature of urban slums. In countries like South Africa, urban slums like Khayelitsha have provided the highest crime stats in South Africa’s urban areas as reported by the Home Affairs Department.

A study of Cape Town’s informal settlement of Khayelitsha also observed that, in Cape Town’s largest informal settlement (Khayelitsha), community participation imbued in civil society formations cultivated a particular kind of local leadership, and accountability mechanisms built on direct engagement with city leadership’. This has resulted in the gradual development of Khayelitsha into a semi-formal settlement and allows livelihoods to prosper, rather than destroying the little that citizens have.

The rise of urban slum settlements has been an outcome of rigid and centralized planning. Governments in the developing world tend to centralize town planning and at the same time have disconnect with the needs and expectations of urban dwellers. The case from Zimbabwe makes a good example to elaborate this point further. ‘

The ideal policy change in Zimbabwe could be in the form of devolution of power as enshrined in the 2013 Constitution where provincial council are given power to oversee and make decisions for their communities. It is an ideal method because they use a democratic participant approach in combating illegal settlements by urban poor.

Another social catastrophe to emerge from urban slum settlements is a fairly new phenomenon in Zimbabwe, of vendors who now stay and work on the streets. The economic challenges Zimbabwe is facing has resulted in the informal sector cutting costs by staying, sleeping and working on the streets of various urban centers in Zimbabwe. The consequence has been that local authorities do not have ablution facilities to offer these citizens and resultantly there has been a rise in communicable water borne diseases.

Last year, typhoid wreaked havoc in Gweru, Zimbabwe’s third largest city due to poor sewage and WASH systems. As a policy measure there is need for ‘on the speed’ town planning to ensure that water service is available to the citizens through even stationing a water bowser and mobile toilets, because efforts to remove them from the streets were in vain.

In other words, council and informal sector representatives have to work together and design an acceptable plan so as to end the social catastrophe of water borne diseases. In the past, Harare used to have cloak rooms and temporary shelters for citizens on the go and it is time local council reactivate these facilities.

One of the best policy measure authorities can do for slums is what is known as a slum upgrade. A 2006 paper titled “Combating the challenges of rise in urban slums in cities in developing world: a case study of Lagos” suggests to authorities that instead of ‘taking a confrontational attitude of demolition threat, they should strive to create an enabling environment under which people, using and generating their own resources, could find unique local solutions for their housing and shelter needs. This conceptual approach is referred to as slum upgrade.’

There is also need to conduct slum upgrades because they provide a win win and humane approach to the situation.

An example of slum upgrades is Caledonia, in Harare which was once an unplanned slum but government later took it up in the under UDCORP and is now a decent high density suburb. Images of a distraught Zim Dancehall musician Soul Jah Love trying to prevent authorities from destroying his home come to the fore and such situations can be avoided. In local setting much of the slum upgrade work has been done by international financiers. These include work by businessman and philanthropist Bill Gates and his wife Melinda through The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation funded upgrade of Harare’s populous Mbare suburb.

As a form of policy governments should be accommodative to efforts by development partners to provide citizens with basic services, but the challenge in Africa is that these development agencies and governments fail to co-exist due to differing political ideologies.

Governments can also leave the actual house building to the beneficiaries themselves to use their own resources, such as informal finance or family labour and various other types of community participation modes to build their own houses. Through the sites-and-services scheme, beneficiaries of land allocated by government could also build their houses at their own pace, depending on the availability of financial and other resources.

Governments need to tap into Indigenous Knowledge Systems (IKS) which is the knowledge base used by past generations to construct decent housing. IKS is rooted in past tradition and has been recognised by global financiers like World Bank as a valid knowledge base.

Indigenous Knowledge Systems (IKS) are not a new phenomenon as they date back to the history of Zimbabwe and was part of the African Culture before the colonisation. The government is encouraged to engage this body of knowledge and tap into the soil abundant in different locations in urban slums like Epworth Gada 5 area which has loamy soil and can be harnessed to construct decent housing. In recent times there has been muted production from cement manufacturers and there is now a shortage of the product on the market.

There are many catastrophes being caused by urban slum settlements in the communities. At a policy level there is need to give communities transformative power to determine and plan their own settlements with reasonable oversight from central governments.

Comments