Contract farming sustains livelihoods

Yoliswa Dube Features Reporter

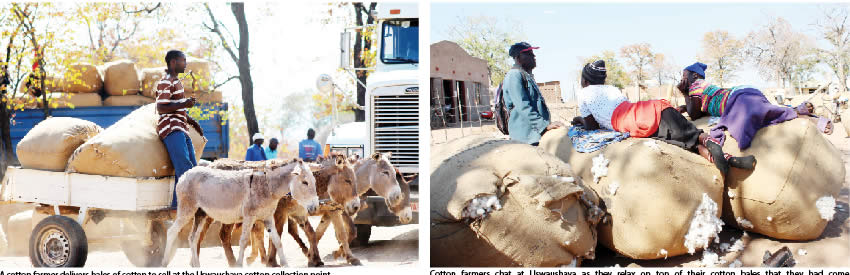

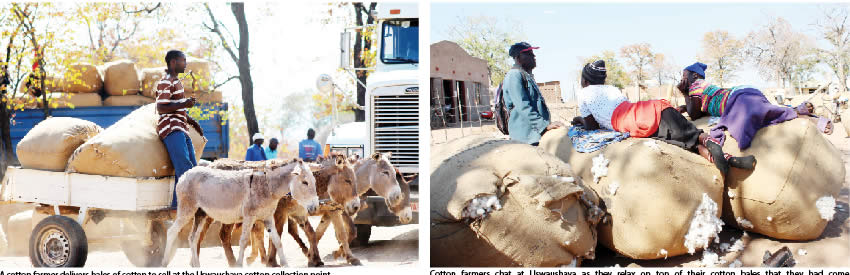

USWAUSHAVA cotton collection point in Chiredzi was a hive of activity recently. People walking back and forth to get their produce registered, others gathered to discuss cotton prices. Some were arranging cotton bales for inspection while others lay on top of theirs as they waited to get them weighed.Company representatives were busy with pen and paper, recording farmers’ cotton harvests.

Others were merely in the midst of the action, probably fascinated by it or just enjoying the music being belted out by the large black speakers at Uswaushava Business Centre. They simply loitered in the commotion.

A “restaurant” that sells freshly slaughtered chicken, isitshwala and vegetables cooked on an open fire has since sprouted along the Masvingo-Chiredzi highway, right in front of the business centre. Scantily pitched tents and neatly laid tables are set at the heart of all the activity.

Customers are treated to a memorable dining experience. No fancy view, just a bustling highway on one end and bales of cotton on the other.

All the cooking is done in full glare of the diner, a la carte style. The ambience is unique.

“Cotton farming in this area has been the reason why my business is growing. I realised that each time farmers brought their cotton here for sale, they had no access to a decent meal nearby,” said Maria Chidungure, the self-proclaimed head chef at this highway “restaurant.”

“It’s quite a straightforward business. I make sure I have chickens, fresh vegetables and mealie-meal. Beef is also on the menu but it’s not always available,” she added, as she cleaned a bird she had slaughtered a few minutes earlier.

The entrepreneur, who has taken advantage of contract farming in the area to grow her food business, said cotton farming had created a significant number of downstream jobs in Chiredzi.

“Things are tough for everyone in the country right now but the most important thing is that we’ve means to earn a living and ensure that our children don’t drop out of school due to financial constraints,” said Chidungure.

Contract farming, where a growing interest in linking up smallholder farmers with larger business operations to produce and market certain agricultural commodities was advocated for by the World Bank and others since it seemed like a perfect “win-win” situation.

The great cotton boom from the 1990s when smallholders entered cotton production in a big way was driven by contract arrangements, initially with the parastatal Cottco, and then with a variety of companies following liberalisation.

Through the arrangement, smallholders are expected to get access to inputs and markets while agribusinesses get guaranteed products at good prices and at scale, without having to take over large pieces of land.

But over the years, the system has failed scores of farmers who continue to rake in low profits.

Some farmers said the amount of time and inputs invested in the cash crop did not match the outputs as they continued to record low profits.

Most were however grateful to have something in the bank after each farming season. “For me, it’s no longer an issue of profits but having a stable source of income, the money I get is enough to ensure my children stay in school and have a decent meal before they go to bed every day,” said Sheunesu Garauzive, a cotton farmer in the area.

“I know cotton farmers across the country are complaining about low cotton prices but they need to look at the bigger picture, times are tough for everyone.”

Farmers in Uswaushava were rather secretive about cotton prices, oblivious of the fact that the cash crop’s selling rates are a public secret.

“I just came with my cotton here but I’m not sure how much it’s selling for, I suppose we’ll soon find out,” whispered Venencia Mhari. “I heard others saying it’s selling for 60c per kg,” she added.

A bale of cotton weighs about 200kg with a kilogram costing 60c, so its average price is $120.

Following a good harvest, a farmer may fill between seven and 40 bales of cotton.

The problem is that the cash crop is not planted all year round so the dividends are only for a short period of time.

“It wouldn’t be bad at all if cotton prices rose to $1 per kg,” said Lazarus Hove, another cotton grower.

“The problem is that cotton is not properly marketed in Zimbabwe and its selling prices are too low. At the end of the day, we don’t benefit much. This year I’ve done reasonably well though. After sharing dividends with my contractor, I had 17 bales of cotton left but four have been used to pay for labour. I have 13 bales now, which amount to $1,560 at $120 per bale.”

Because the money is seasonal, Hove said, it does not amount to much. “It’s not a lot of money at the end of the day. I earn a decent living but the inputs just don’t match the total gains,” he said.

Hove said big companies were benefiting from cotton farming at the expense of the ordinary farmer.

“I spend almost a year on the project and only have $1,560 to show for it. In essence, that’s about $130 per month which is not enough to adequately sustain a family. Unfortunately though, there is no other market except this one so it’ll have to do. But I’m grateful, at the end of the day, that I get something tangible from my efforts,” he said.

Almost all parts of the cotton plant are used in some way including the lint, seed, linters, stalks and seed hulls. The fibre from one 227kg cotton bale can produce 215 pairs of jeans, 250 single bed sheets, 1,200 t-shirts, 2,100 pairs of boxer shorts, 3,000 nappies, 4,300 pairs of socks or 680,000 cotton balls.

Cotton lint is spun then woven or knitted into fabrics such as velvet, jersey and flannel. About 60 percent of the world’s total cotton harvest is used to make clothing, with the rest used in home furnishings and industrial products.

Over half the weight of unprocessed cotton (seed cotton) is made up of seed. The most common uses of cottonseed are oil for cooking and feed for livestock. Cotton seed is pressed to make oil.

Cottonseed can be made into a meal and is a popular feed for cattle and livestock as it is a good source of energy. Cottonseed oil can also be used in a range of industrial products such as soap, margarine, emulsifiers, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, rubber, paint, water proofing and candles. Cottonseed oil is cholesterol free, high in poly-unsaturated fats and contains high levels of anti-oxidants (vitamin E) that contribute to its long shelf life.

Cotton linters are fine, very short fibres that remain on the cottonseed after ginning.

Linters are used in the manufacture of paper (such as archival paper and bank notes) and as a raw material in the manufacture of cellulose plastics.

Linters are commonly used for medical supplies such as bandages, cotton buds, cotton balls and x-rays.

Farmers in Chiredzi have contracts with a number of cotton companies including Cottco, China Africa and Alliance Ginneries Limited. Former Cotton Ginners’ Association president Godfrey Buka said cotton prices were based on individual companies.

“It’s no use talking to associations because at the end of the day, it’s a matter involving an individual company because companies are the ones that settle for the prices they’re willing to buy for,” said Buka.

Comments