Africa’s shackled tongues, hands

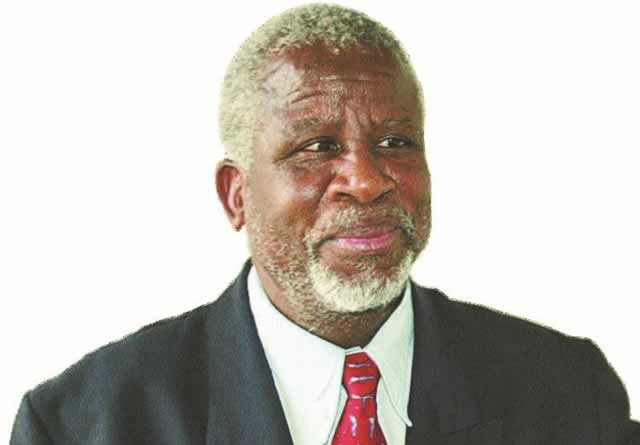

Perspective, Stephen Mpofu

Europe’s colonisation of Africa lingers on albeit in the minds and tongues of the African people, many decades after the physical retreat of the white man as the buffeting winds of change roared across the continent from the West through the East and Southern Africa, sweeping away colonial outposts as it went.

Critics will say that what the generality of Africans call “our independence” is a misnomer, to say the least.

As Zimbabwe’s leading historian, Pathisa Nyathi puts it without mincing his words, the independence of not only Zimbabwe but of older states before it, simply meant that the erstwhile oppressed black people of this continent merely walked with the men whistling and the women ululating shrilly, into the footprints of the departed racist oppressor while their minds and hands remained shackled by the hovering shadows of different European colonial powers.

To authenticate Mr Nyathi’s disquiet at Africa’s independence misconstrued as total freedom, you (yes, you) should look at the war of tongues, as it were, raging on in the West African State of Cameroon previously ruled by the British in the South and by the French in the North and thereabouts.

In spite of that country’s long years of its supposed Uhuru from the two previous colonial powers, divided Cameroonians are still at each other’s throats with English speaking Cameroonians not seeing eye to eye with those still under control by the ghosts of their former colonial power.

Recently lawyers in the English speaking region of Cameroon have fiercely been opposing the intrusion in their courts by French speaking lawyers.

Right now parents in English speaking Cameroon are preventing their children going to school as teachers there are on strike apparently to protest their conditions of service.

What remains an unspoken truth, in the circumstances, is that the two foreign languages have kept at bay, as though it were a leper, any lingua franca that would otherwise unite Cameroonians as one people, one nation.

The linguistic story of Cameroon repeats itself here, in our own motherland where English remains the official language nearly four decades into independence from British colonial rule.

Is it not a shame that the elite in power often deliver their official speeches in English even in their own regions of birth instead of in their lingo, with an interpreter then conveying the message in the common language there?

The upshot of the continuing domination of the former oppressor’s language in the minds of Zimbabweans has not only prevented the development of a lingua franca between and among different tribes in the different regions of our country; it has and continues to perpetuate disunity among Zimbabweans in the different provinces of the country.

Worse still, any prospect of a common language being promoted as a lingua franca for peoples in Sadc, in the same way as Swahili is almost universally spoken in East Africa right through to the Congos, remains an intangible dream.

It is for that desirable language understood by, and unifying Africans, that the proposed introduction of Swahili in the new school curriculum in this country apparently seeks to achieve.

For now, however, mental colonisation remains a fact with the stalking ghost of the foreign colonial master hovering at our shoulder, to the extent that a dearth exists in literature in our indigenous languages, with some book publishers making an impassioned plea for Zimbabweans to write books in their mother tongues which English has continued to shove in the shade even after so many years after liberation from colonial oppression and divisive tactics to keep Africans disunited and so easy to manipulate by the so-called native commissioners, who were representatives of successive white racist regimes holed up in Salisbury, which is now Harare.

What is even worse, a nation touting itself, and being touted abroad, as the most literate on the African continent with a literacy rating of over 90 percent, has failed dismally to tell the world the story of its liberation from the shackles of colonial rule and social and political deprivation in its mother tongues.

What, for instance, are Zimbabwe’s renowned historians doing instead of telling the full story of where and how Zimbabwe became what it is today even in their own indigenous languages which might eventually die, as has virtually happened to the language of the first inhabitants of this country, the San whom the colonialists pejoratively called bushmen. Their language was not recorded for its continuity so that now only a few remaining San elders speak a sprinkling of that doomed tongue.

Or are Zimbabwean academics, for instance, stone drunk on the drags of colonialism and so cannot wean themselves from their colonial mother to chart the way forward through a new historical perspective, the revolution that brought Uhuru to this country, instead of their full blooded adherence to European and other, foreign history?

More importantly, why are the men and women who took part in the armed revolution not telling their story as it is and as a campus for showing the way forward for the revolution that brought us independence and freedom to continue unimpeded until the end of the earth?

Do they want historians from our former colonising power to tell that story, apparently believing that those writers will tell all about the racism and brutalities of their own kith and kin against our own people in the heydays of colonial rule? If that is the case, nothing could be more wishful thinking.

But even more mind-boggling, where are the gallant men and women who went through the thick and thin of the armed revolution but have not appeared in print narrating their experiences in the bush where they ran the gauntlet of both enemy Rhodesian soldiers and snakes and mosquitoes as they made their way home from neighbouring foreign lands with freedom borne in their AK rifles?

Many of them did not boast mere, functional literacy. No, they were highly educated men and women who later held down high-ranking positions in Zanu-PF and its government over the years.

In the early years of our independence the masses heard promises from their leaders that steps would be taken to ensure that prominent individuals or groups of Zimbabweans knowledgeable about the armed revolution would set out to chronicle their experiences as part of the body of the history of liberation of the motherland from foreign rule.

One therefore expected that such accounts would not be perfumed or doctored but that they will tell of the liberation war as it was – the joys, if ever there were any, and the brutalities, such as attacks by Selous Scouts and massacres of freedom fighters by the Rhodesian air force in their failed bid to keep this country under the shackles of white oppressors.

Regrettably, however, some prominent participants in the armed struggle have since met their autumn, leaving behind a permanent void in the history of the making of Zimbabwe.

However, many very literate participants in the struggle remain in both the party and in the government but, sadly enough they appear disinclined to leave behind a mark in their lives by telling their story in the prosecution of the liberation crusade.

But why this laissez faire approach to a history so important to our country, like blood to life? Are these people still imbued with the patriotism that made them abandon their education and jobs to join the boys and girls in the bush, or have they become apologists for imperialists bent on a new hegemonic presence on the cold ashes of their colonial hey days in Zimbabwe and in other former colonial possessions, using dirty money to prostitute the minds of our people to sell their country in order to grow potbellies?

This pen believes strongly, as Mr Nyathi and other Zimbabweans do, that those who wielded arms to liberate our country and are still on their feet should leave behind a historical legacy of the revolution; otherwise future generations, including their own children and children’s children will write them off as mere proverbs for not being torch bearers for them by advancing the cause of the revolution but choosing instead to hibernate in comfort zones.

Comments