Censorship and its discontents

Stanley Mushava

Zimbabwe’s new board of censors was greeted with foreboding like a beast of the apocalypse last week.

Sceptics, apprehensive of political interests and cultural scruples muzzling free expression, have circled the board’s colonial origins and cast it as a lost fossil in independent Zimbabwe.

However, flagging censorship as inherently ill-intentioned and unnecessary is easily an overstated reaction.

Censorship can be a progressive tool in a democratic society, protecting citizens from age-inappropriate content, hate speech and security risks.

It can equally be a primer to the Dark Ages, inhibiting knowledge, muzzling dissent, baiting minorities and shoring up privilege.

Establishing the uses and abuses of censorship and holding it up to democratic scrutiny could be a more ideal direction.

Censorship is a museum of dystopian imagery, from Catholic inquisitors burning heretics at the stake, to Islamic extremists spraying bullets in a newsroom or sawing off an artist’s head.

When Wole Soyinka flees his president by boat before dawn, “The Rhodesian Herald” goes to press with blank spaces and Ngugi waThiongo writes his novel on tissue paper in prison, it equally comes back to the written word as a site of contest.

Before Photoshop was an entrepreneur’s dream, it was a dictator’s plaything, with Joseph Stalin’s censors airbrushing his fallen opponents out of history, shoving them down Orwellian memory holes forever.

Still, rather than respond to the new board of censors with sweeping cynicism, it is more profitable to hold them up to democratic expectations seeing as the board is already in force.

The board, appointed last week in terms of Censorship and Entertainment Control Act Chapter 10:4, is tasked with “controlling and regulating the media and film industry and examining any article or public entertainment submitted to it.”

Police spokesperson Senior Assistant Commissioner Charity Charamba, Catholic priest Fidelis Mukonori, former culture minister Aeneas Chigwedere, Konzani Ncube, Bona Chikore, Runyararo Magadzire, Chief Nyamukoho Samson Katsande, Regis Chikowore, Shingai Rukwata Ndoro, Chenjerai Daitai and Tungamirai Muganhiri sit on the board.

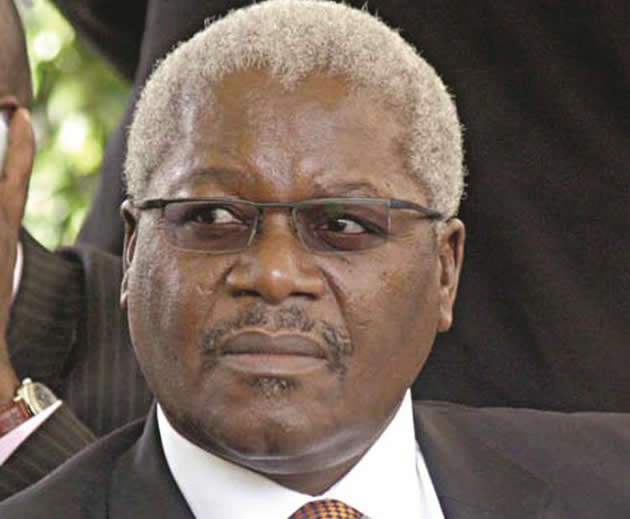

Home Affairs Minister Dr Ignatius Chombo named the prohibition of public entertainment which may undermine morality, public order and peace among the board’s responsibilities.

“It is a well-known fact that the Constitution of Zimbabwe has a provision for freedom of artistic expression, cultural beliefs and association. However, the same Constitution through the Act of Parliament empowers the Board of Censors to ensure that these freedoms are reasonably limited so that they do not infringe on other people’s rights,” said Dr Chombo.

The minister alerted the board to the difficulties of administering its assignment in an environment where there is heightened scrutiny by members of the public, internet penetration and social media use.

However, this could be just the ideal setting for the board. Operating under the sceptical gaze of the public will ensure that the censors are democratically grounded.

The challenge of the internet is also an opportunity for the board not to operate in opacity and detachment but to maintain touch with evolving attitudes and changing times.

The censors are tasked with gazetting banned and prohibited material, reviewing films, advising the Home Affairs minister on issues arising out of the application of the Censorship and Entertainment Control Act and processing results of the Publications Committee.

The immediate concern is the banning of publications as a function of the board, although it is difficult to pinpoint any high-profile scuffle since the banning of Dambudzo Marechera’s The Black Sunlight more than two decades ago.

The ban, which was later successfully contested by Musaemura Zimunya, was motivated by the censors’ perception of Marechera’s sophomore release as obscene and blasphemous, two of the offences proscribed by the 1967 Censorship and Entertainment Control Act.

Banning of books is controversial worldwide, especially since proscribed features lend themselves to fluid definitions. Some of the world’s best-known authors are banned and hunted down as dissidents in their own countries, potentially suppressing immortal contributions to mankind’s intellectual record to pander to transient politics.

Censorship also moves in discreet ways. In recent times, there have been public calls to come to what may be called a definitive canon of African culture and Zimbabwean history, coupled with proposals to push foreign texts and foreign ideas out of the school curriculum.

In 2015, I called out in these columns Ambassador Agrippa Mutambara’s proposal to the Parliament to kick William Shakespeare and Chinua Achebe out of Zimbabwe’s literature classes and replace them with liberation war literature.

Later that year, a symposium convening culture experts, writers and the Curriculum Development Unit had a prescriptive vibe also circling around the idea of a definitive African culture.

It may be enough to suggest education is not exclusively determined by the content of the book but the critical capacity of the reader. Certain discussions in elite corridors seem to be motivated by an ungenerous estimation of this capacity.

It would be interesting to think about John Milton’s answer from his classical Areopagitica address. The speech, set to biblical analogies, debunks the idea that a committee can gazette certain books out of public circulation on moral, cultural or political grounds.

“Not to insist upon the examples of Moses, Daniel, and Paul, who were skilful in all the learning of the Egyptians, Chaldeans, and Greeks, which could not probably be without reading their books of all sorts; in Paul especially, who thought it no defilement to insert into Holy Scripture the sentences of three Greek poets, and one of them a tragedian,” Milton points out.

Anyone thinking about the circulation of cultural products in a perspective way needs to read the whole document.

George Orwell’s proposed preface to Animal Farm cites, on the flipside, the phenomenon of the renegade liberal given to the assumption that one can only defend democracy by totalitarian methods.

“If one loves democracy, the argument runs, one must crush its enemies by no matter what means. And who are its enemies? It always appears that they are not only those who attack it openly and consciously, but those who ‘objectively’ endanger it by spreading mistaken doctrines. In other words, defending democracy involves destroying all independence of thought,” writes Orwell.

It will be important for the new board to bring none of these attitudes aboard, presuppose a special mantle to hand-hold the development of knowledge or limit cultural, civic and academic freedoms, bar the overtly criminal.

Comments