Nkomo conscientised blacks on their rights

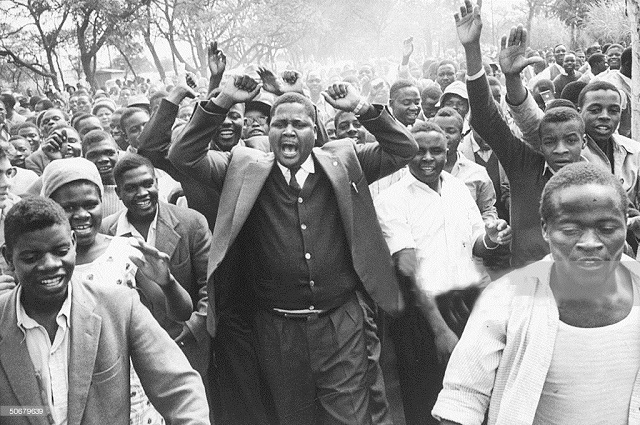

Dr Joshua Nkomo (centre), as leader of the National Democratic Party in the early 1960s, leads a protest march in this file photo. Inset: The late Vice President Dr Joshua Mqabuko Nkomo

Saul Gwakuba Ndlovu

One important fact we should remember as we collectively celebrate the life of the late Vice President, Dr Joshua Mqabuko Nkomo, who died on July 1, 1999, is that he became a legend in his lifetime.

That was particularly so because of the way he would slip through Rhodesian police nets, leaving Rhodesian security personnel guarding at times residential houses in Salisbury or in Lusaka the whole night only to hear him addressing the media in Bulawayo or in Dar es Salaam the following morning.

That fascinated his myriad of supporters.

That was why and how he came to be called “Chibwechitedza” (the slippery rock), a name by which he came to be fondly called throughout the country.

That apart, when talking about Dr Nkomo, two questions arise: What exactly did he achieve for his country that we should highlight all the time?

What was unique about Southern Rhodesia that caused it to take much longer and tougher measures to decolonise than other former British colonies, especially Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) and Nyasaland (now Malawi), that were the other components of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland.

We should remember that the British colonialists established themselves in our country by brutal armed conquest and ruthlessly suppressed subsequent uprisings thereafter.

Those military campaigns, coupled with a number of repressive laws generated a great deal of deep-rooted fear among the displaced, exploited and voiceless black people of this land.

Fear of the white people was a very, very common social and political characteristic of this country’s black population’s socio-cultural attitude before Dr Nkomo emerged as their national leader.

We feared not only the whites but their laws which were mostly not for but against us. One very good example of such laws was the 1960 all-embracing Law and Order Maintenance Act. Others were the Unlawful Organisations Act by which four or five African-led political organisations were successively banned between 1959 and 1964.

Banning of African nationalist parties was immediately followed by mass detention of their officials and members, and the confiscation by the white settler governments of the parties’ properties, and on some occasions even some personal possessions of some of the leaders.

Displacement of some leaders would also be carried as was the case with the veteran trade union leader, Sergeant Masotsha Ndlovu who was removed from Bulawayo and was dumped at Buhera, some 400km away from his original place of abode.

Such draconian measures created fear, not just of the oppression but of those enforcing them, the white police and military personnel.

Fear of the white people dominated the pre-Nkomo black community to such an extent that they were referred to by elderly black people as “the gods of the earth down below”, omlimu baphansi.

Dr Nkomo removed that fear from the black community and in its place created self-confidence, self-pride and, above all, courage to demand and assert their rights as the indigenous owners of this country.

He is remembered as the leader who successfully urged black people to stand up for their human rights, and said that the only qualification for one to be entitled to one’s rights is to be human, nothing more and nothing less.

The second achievement was of an international diplomatic nature, and it was the recognition of Southern Rhodesia by the United Nations as a British colony. The British Government had before that vigorously denied that it had the responsibility to steer Southern Rhodesia to full nationhood under a black government because, it maintained, Southern Rhodesia was self-governing under a white minority settler regime.

The UK United Nations representatives said their Government had no authority over Southern Rhodesia’s African affairs because those were an internal matter over which only the Rhodesian Government had constitutional authority.

Their argument was that that was the country’s legal constitutional position since 1923 when Cecil John Rhodes’ British South Africa Company ceased to administer Southern Rhodesia, and the country’s white minority settlers then opted for what Britain termed “internal self-government.”

That type of administration was then conferred on Southern Rhodesia by means of what are known as “Letters Patent,” a phrase that means an open document from a sovereign or government conferring authority and/ or rights, in this case on the minority white settlers to the exclusion of the indigenous black majority.

The British Government theoretically undertook to reserve authority to veto any Southern Rhodesian legislation that was negatively discriminatory against the social, economic, cultural or political interests of the black majority.

However, at no time did it intervene when discriminatory, dispossessive, displacing laws such as the Land Appointment Act of 1930, the 1934 Industrial Conciliation Act which was amended in 1959, the repressive Law and Order Maintenance Act of 1960, and the 1959 Unlawful Organisations Act were passed.

A more or less similar colonial administration had been created in the Cape Colony in the 1880s when Britain granted that colony so-called internal self-government.

Cecil John Rhodes became its prime minister later, and it was while he was in that powerful political position that he organised the BSAC, and then invaded Mashonaland on the strength of a concession which King Lobhengula signed very soon thereafter but in vain to disown.

The Southern Rhodesia situation was a unique colonial case in which a white minority settler community had in its control means of power such as an army, a police force, a prison service and, above all, a legislative assembly that were not in effect answerable to the British Government.

Initially, Britain appointed the colony’s governors such as Sir John Kennedy. However, the man who occupied that position during the turbulent period that culminated with the convening of the Lancaster House constitutional conference, Sir Humphrey Vicary Gibbs, was born and bred in the Nyamandlovu commercial farming region in Southern Rhodesia.

That type of colonialism was very much different from what obtained in Northern Rhodesia (Zambia), Nyasaland (Malawi), Kenya and elsewhere in that it was controlled and directed locally and not from the metropolitan country. The other mentioned former British colonies were, in fact, protectorates, hence the comparative ease with which they became independent.

The Smith Rhodesian Front regime tried to use that argument to extract legitimised independence from Britain but failed because of Dr Nkomo’s concerted campaigns throughout Africa, and other parts of the world, particularly at the United Nations. The Smith regime then decided to declare unilateral independence (UDI) on November 11, 1965.

Dr Nkomo had to educate the world about the rather difficult Southern Rhodesian colonial situation, through the United Nations where in 1962 his international campaign reached a climax when that world body decided that Southern Rhodesia was indeed a colony over which the colonial power, Britain, had not only constitutional authority but also legal, moral, historical and constitutional responsibilities.

It was a cause of immense happiness for the vast majority of the people of Zimbabwe when in the middle of that year, the world’s mass media, both print and electronic, announced that historic UN verdict.

“That is an important moral victory for the oppressed people of Zimbabwe”, commented the then Zapu Vice President, Dr Samuel Parirenyatwa, at the Salisbury Zapu Vanguard House head office.

The chief British UN diplomatic representative, a very senior diplomat, resigned not in protest against that verdict, but in sympathy with Dr Nkomo.

Henceforth the majority of the world’s nations supported the Zimbabwe liberation struggle, and the decolonisation of Southern Rhodesia became a permanent item on the UN’s appropriate committee’s agenda until Zimbabwe was born on April 18, 1980.

Dr Nkomo and innumerable other freedom fighters who shed tears, sweat and blood to bring about Zimbabwe should be honourably remembered.

l Saul Gwakuba Ndlovu is a retired, Bulawayo – based journalist. He can be contacted on cell 0734 328 136 or through email. [email protected].

Comments