The endless search for a new high in Byo

Bruce Ndlovu

“Do you know anyone that can sell me some embalming powder?” asked *Thabani Moyo (24) as he fiddled with a joint of marijuana that he had been carefully preparing for a few minutes.

On a table in front of him lay an upturned bottle top half-filled with gin, and occasionally he would drown his forefinger in it, drawing drops of alcohol which he used to delicately run over the joint.

As Moyo sat there, carefully tending to the joint, he indeed looked like a mortician embalming a recently deceased body.

“There’re some guys who want to buy some and they thought I could help because of my profession. They’re offering a lot of money for it,” he said as his gas lighter’s flame flickered, and in the next instant lit one end of the joint which had been twisted into a knot.

It was on a Friday evening in Bulawayo and Moyo, a nurse at Mpilo Central Hospital, had gathered with a few friends at a shop ran by *John Phiri (23), a tailor in the city. Phiri’s shop is the ideal nest for the group of drug-loving friends who want to puff or drink away the stresses of the day away from the eyes of a condemning public and law enforcement officers.

On that particular Friday, the noise from their random drug talk, which comprises a large part of their early evening conversations, competed with the mechanical harmony of sewing machines.

“Generally, embalming powder is harder to get. The guys that want it are offering to buy it in bulk,” said Moyo.

His encounter with embalming powder consumers tallied with a report from our sister paper, the Sunday News, last year, which stated that, acting in cohorts with employees in morgues, city drug dealers were now peddling embalming powder as the drug of choice.

While Moyo may have been ignorant of how it delivered its high, chemical engineer Mr Khonzaphi Dube confirmed at the time that it was possible for embalming chemicals to be abused as formaldehyde, methanol and ethanol, chemicals used to make the compound, are highly intoxicating.

“Ethanol and methanol are both alcohol while formaldehyde is sort of a modified alcohol. It can even be worse than ethanol and methanol. So yes, it’s possible for the compound to be used for intoxication purposes,” said Mr Dube.

For Moyo, however, the ultimate high lies in a different drug.

While some might be content to smoke any “grade” of marijuana, Moyo instead is part of a growing legion of city youths obsessed with a strain he and others on the streets call skunk.

It is not clear when it became a craze in Bulawayo, but in the last two years, it has tightened its grip on those that are looking for the levels of intoxication that normal strains of marijuana cannot deliver.

While he is not sure of the exact science, according to Moyo, skunk is a strain of marijuana that has been dried after being soaked in codeine or promethazine, two addictive chemicals found in cough syrups.

A twist of skunk, sold on the streets of Bulawayo ranges between $3 and $5, while the asking price for even stronger and more intoxicating strains can be as much as $20.

Although he holds it in high regard, Moyo, a recently graduated nurse, accepts that a skunk induced high is unpredictable, which sometimes complicates his job.

“They’re other strong strains of weed (marijuana) like the white widow and three fingers but none of them have the same effect as skunk. You never know what state it’s going to leave you in after you take it. For example, one day I took it before work and ran through all my duties at lightning speed. At other times, however, I find myself getting lazy or confused,” he said.

Moyo’s account of the unpredictability of skunk is corroborated by Phiri the tailor.

While Moyo was able to finish his studies at the Bulawayo Polytechnic, Phiri dropped out in his second semester, as the skunk inspired daze he constantly found himself under swept him away from lecture rooms and into Bulawayo’s back alleys.

“Skunk is just different. You can feel it when it hits the back of your throat and sometimes you feel like someone is piercing the inside of your head with needles. But some of the stuff that the boys are taking out there is not the real thing,” said Phiri.

An unidentified drug dealer, a surprise guest who joined the boys on that Friday evening seemed to confirm Phiri’s misgivings.

The young man, who looked barely out of his teens, boasted about his bedroom pharmaceutical skills that have seen him cook up concoctions that made him a darling amongst those who, for $3 per twist, were seeking the thrill of the ultimate high.

“First you mix the weed (marijuana) with domestos (bleach) then you allow it to dry after adding some methylated spirit. You then spray it with one of those air fresheners so that it loses some of the smell. After three weeks of drying, it’s ready for the streets,” he said.

Moyo conceded that such a mixture might scare away some smokers, although he hastened to add that this was not the most potent high that emerging drug princes were peddling in the City of Kings.

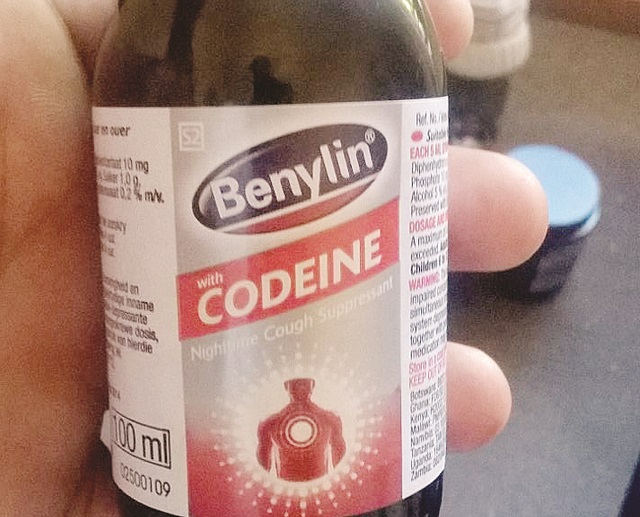

“All the young boys now drink Benylin. Everyone thinks Bronco (BronCleer) is the problem but really, on the streets Benylin is winning,” said Moyo.

This was confirmed by *Thulani Ncube (20), a school dropout from an affluent family that, despite his refusal to smoke marijuana, makes a daily pilgrimage to Phiri’s shop to indulge in his intoxicant of choice.

“I can drink two or three bottles of BronCleer without feeling anything but with Benylin, one is enough. Right now BronCleer costs $4,50, Benylin costs $9 and PP (Histalix) costs $10. Their pricing should tell you all you need to know about which one gives you the greatest high,” said Ncube.

Ncube, a former pupil at Petra High School in Bulawayo, said Benylin was popular because of its appeal to youths who do not conform to the usual stereotype of what a typical drug addict looks like.

An unemployed, uneducated or troubled young man from a broken family is what many picture when drug addiction is discussed. As the popularity of cough syrups steadily sips into families and communities that are considered stable, this is proving to be less so. Even the most unlikely people are falling victims to it.

“We have a few girls admitted to our ladies admission ward, St Mary’s I, for cough syrup addiction. Most of them are from the country’s institutions of higher learning. The most painful part is that they’re mostly very young,” said Ingutsheni Central Hospital public relations officer, Mrs Vongai Chimbindi.

According to Ncube, he went to school while high mainly to woo girls who fell for words that his sober tongue would otherwise not utter.

However, his friends have been giving away the game as due to their Benylin addiction, to the alarm of their parents and teachers, some had begun losing their teeth.

Dr Chris Mpofu, a medical practitioner at Mpilo Central Hospital, said this was usually a tell tale sign that one was abusing cough syrups.

“Codeine belongs to a class of drugs called opioids and the use of opioids leads to a dry mouth. It has an atropine-like effect on the mouth, which means it makes it very dry and a chronic dry mouth will lead to acid erosion of the enamel, discoloration and loss of teeth. This dryness of mouth is called xerostomia,” said Dr Mpofu.

Despite such adverse side effects, Ncube said that it was unlikely that he was going stop his cough syrup consumption anytime soon.

What has made the syrups particularly attractive to young people in the more affluent suburbs of the city has been the constant endorsement they get from hip-hop superstars in America.

From the project apartments in Atlanta to the Cape Flats in South Africa, lean, as cough syrups are referred to in hip-hop culture, has become a headache for parents and authorities.

However, even the heavyweight ambassadors of cough syrup addiction have not been spared its effect, with rappers Lil Wayne and Rick Ross reportedly suffering seizures from their consumption last year.

While the two rappers were quickly rehabilitated and put back on stage, redemption does not come so easily for Bulawayo’s addicts, as the city does not have specialised rehabilitation centres.

“Currently, we don’t have a separate rehabilitation facility because for some strange reason, we’re not getting as many (addicts) in our system to warrant a specific ward. We do get some and they work with our psychologists because remember for drug addiction, you don’t need a specific drug or treatment but psychotherapy,” said Ingutsheni clinical director Dr Wellington Ranga.

With it already banned in Zimbabwe, it remains to be seen what other measures can be put in place to combat BronCleer and its pharmaceutical cousins.

Tighter controls at the border might help deter the illegal importation of what the Medicines Control AuthorityCouncil called “the most abused over the counter drug in South Africa” last year.

A pushback against BronCleer has already started south of the Limpopo, after its manufacturers, Adcock Ingram, reduced the alcohol percentage contained in a single bottle of the cough mixture.

In 2014, the Zimbabwean government also engaged the Botswana government to ask for stricter enforcement on the sale of the over the count medicine whose empty bottles now compete for space in rubbish bins with empty liquor bottles in urban Zimbabwe.

While health professionals do public outreach and awareness programmes and authorities scratch their heads for a solution to an increasing drug problem, young people continue their unending search for the next high on the streets of Bulawayo.

*Not his real name

Comments