Are women poorer? Tackling the issue of feminisation of poverty

Andile Tshuma

It is sometimes difficult to define poverty, to measure it and to tackle it as a discourse.

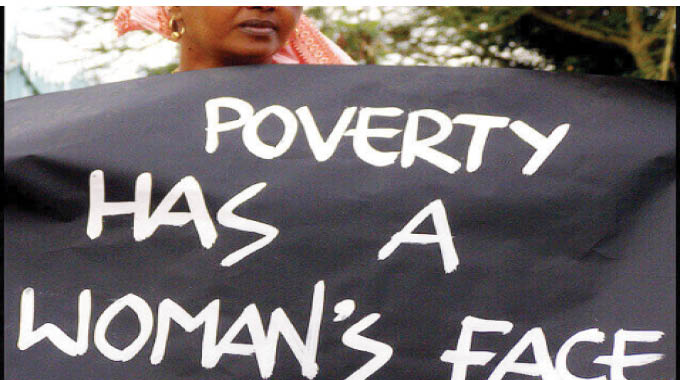

But it is not rocket science to realise that in so many spaces, women and girls are used in representations and portrayals of poverty in communities.

While it is true that women are often more vulnerable and more affected by poverty in many ways, is it really necessary to use a picture of pale skinned, struggling looking mothers nursing hungry looking babies in every brochure or documentary on poverty? Such images can be really depressing in as much as they are aimed at telling a story and reaching out to people, but no sex or gender should be assigned to poverty.

Portrayals of women and poverty are often a result of the complex relationship between gender and poverty.

The relationship between gender and poverty is a complex and controversial topic that is now being debated more than ever before. Although much policymaking has been informed by the idea of feminisation of poverty, the precise nature of the connection between gender and poverty needs to be better understood and operationalised in policymaking.

Poverty is considered as the result of power relations that first of all affect men and women in a different way and in different societies in terms of access to resources.

The different shapes and forms gender inequality and poverty take depend on the economic, social and ideological context.

What should be done to change feminisation of poverty? The unfortunate staggering fact is that the feminisation of poverty is not just a stereotype. Indeed, in many societies, the poorest are women.

A gender perspective enhances the conceptualisation of poverty because it goes beyond a descriptive analysis to look at the causes of poverty. It approaches poverty as a process, thereby giving it a more dynamic perspective.

Children must be socialised in such a way that they know that both parents can be breadwinners therefore doing away with the notion that poverty is associated with the woman.

Gender stereotypes also contribute to the feminisation of poverty. They persist in the labour market in sectors such as engineering and childcare, leading to occupational segregation and the gender pay gap.

The female image should be portrayed in a way that respects women’s dignity instead of ever portraying them as victims.

In a statement to mark International day for the Eradication of Poverty, the Women’s Institute of Leadership Development (WILD) called for the empowerment of women and children to help fight poverty.

“In Zimbabwe, the deterioration of the economic situation has impacted negatively on the quality of life. According to the Borgen Report, 72 percent of the country’s population now lives in chronic poverty, and 84 percent of Zimbabwe’s poor live in rural areas. The adverse effects of poverty are heavily impacting on rural women and natural disasters such as drought have affected yields, this has highly contributed to the rise in a number of households living in acute poverty,” said WILD.

WILD also highlighted that poverty is not only an economic issue, but rather a multidimensional phenomenon that encompasses a lack of both income and the basic capabilities to live in dignity. Malnutrition and limited access to healthcare have also increased the mortality rate countrywide.

Poverty and gender are concepts that have historically been treated in a fairly independent fashion, which explains the specific importance each has been afforded on the political and research agendas.

The most common expression of this idea is the concept of feminisation of poverty. This idea has become popular both in shaping analyses of poverty and poverty alleviation strategies. Thus, targeting women has become one vehicle for gender-sensitive poverty alleviation.

Poor women have become the explicit focus of policymaking, for example, in the areas of microcredit programmes and income generation activities.

There is a need to understand the gender and age-based power relations within households, the mechanisms of cooperation and conflict as well as the dynamics of bargaining that shape the distribution of work, income and assets. Such processes of bargaining do not take place in a social vacuum, however.

They are affected by social norms as well as the differential access to opportunities and resources men and women have outside the household.

According to a report by the UNDP in 2017, women’s combined paid and unpaid labour time is greater than men’s. Although it is often stated that labour is the poor’s most abundant asset, women are relatively time poor and much of their work is socially unrecognised since it is unpaid. Furthermore, when women are in paid work, the return to their labour is lower than the return to men’s labour.

Thus, women on average work more, but have less command over income as well as assets, neither do they always have control or command over their own labour.

In some cases, men may forbid their wives from working outside the household and seclude them. In other cases, men may extract labour from women with the threat or actuality of violence, as for instance, in the case of unpaid women family labourers. Men tend to have more command over women’s labour so that in crisis situations they may be able to mobilise the labour of women, while women generally do not have the reciprocal right or ability to mobilise men’s labour.

Women are less mobile than men because of their reproductive or caring labour activities and because of social norms that restrict their mobility in public. Therefore men contribute to the sad predicaments that women find themselves in.

The gender-based division of labour between unpaid and paid labour renders women economically and socially more insecure and vulnerable to not only chronic poverty but also to transient poverty that can result from familial, personal or social and economic crises, including those that arise from macroeconomic policies, political and ethnic conflict situations or health-related crises such as the HIV/Aids epidemics.

The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, adopted by 189 Member States in 1995, reflects the urgency around women and poverty by making it the first of 12 critical areas of concern. Actions under any of these, whether education, the environment, and so on, help women build better lives. But measures targeted to reducing women’s poverty are critical too.

Governments agreed to change economic policies to provide more opportunities for women, improve laws to uphold economic rights, and boost access to credit. It is time to walk the talk.

While both men and women suffer in poverty, gender discrimination means that women have far fewer resources to cope. They are likely to be the last to eat, the ones least likely to access healthcare, and routinely trapped in time-consuming, unpaid domestic tasks. They have more limited options to work or build businesses. Adequate education may lie out of reach. Some end up forced into sexual exploitation as part of a basic struggle to survive.

Having discussed the many facets that relate to gender and inequality, it is only fair to argue that women are not poorer, it is just the system that is flawed which fails to avail opportunities that make them realise their full potential. Poverty must not have a gender and the stereotypes that synonimise poverty with feminity must fall.

The painful truth though, is that for now, poverty does bear a female face. — @andile_tshuma

Comments