Bulawayo scientist targets ‘zero hunger’ by 2030, conducts research on edible insects

Mashudu Netsianda, Deputy News Editor

TALKING of the UN Sustainable Development Goal (SGD) 2 aimed to achieve “zero hunger” by 2030 would not be complete without mentioning Bulawayo-based researcher and scientist Ms Dorothy Chipo Madamba.

SDG Goal 2 seeks sustainable solutions to end hunger in all its forms by 2030 and achieve food security and improve nutrition.

Ms Madamba who heads the Bulawayo Natural History Museum’s department of entomology did research on edible insects in Zimbabwe based on their specimen collection and established that there are 52 edible species in the country.

The museum specimen data set represented over 1 195 records of 52 unique taxa of edible insects collected between 1885 and 2000.

The Bulawayo Natural History Museum’s entomology department is home to a collection of millions of insect specimens, some dating back to the late 19th century. Entomology is the study of insects.

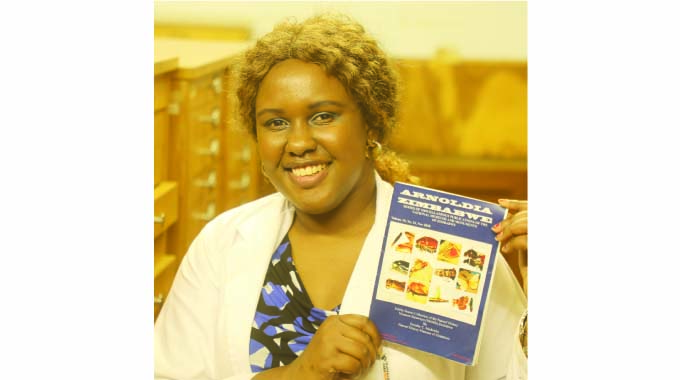

Through her research, Ms Madamba produced a taxonomical paper titled “Arnoldia Zimbabwe” which was published in 2020, and provides insight into a list of the collections that are found in the museum.

The paper describes the edible insect collections of the museum, providing event data as well as a quantitative description of the holdings.

The data is made accessible through a link to the GBIF-integrated publishing tool. Seven orders, Coleoptera, Lepidoptera, Hymenoptera, Hemiptera, Homoptera, Orthoptera and Blattadea, 18 families, 36 genera and over 52 species of edible insects are identified and found in Zimbabwe.

The specimens came from a total of 102 localities in Zimbabwe, 45 of these localities had only one species collected from them. Of the top 10 localities in terms of species richness in the museum collection, Bulawayo had the highest number with 23 species collected.

However, the 52 species identified in the museum collection are a fraction of the 524 edible insect species recorded for Africa.

Ms Madamba who holds a BSc in Forestry Resources and Wildlife Management (Nust) and an MSc in Biology (forensic entomology) from Sam Houston State University, Texas, USA, said since joining the Natural History Museum in 2012, she developed a passion for conducting research on edible insects.

Nust

“In terms of research, the issue of edible insects for food and feed has always been the top of my list in terms of insects and that is the area I love focusing on. Although not much funded, it was the most interesting and remains the most interesting to me,” she said.

“As we switched from 2020 to 2021, we started talking about Sustainable Development Goals and Goal number 2 is specific to zero hunger. When it comes to the issue of finding sustainable foods, what better way than to use food that people have been using for ages that has little or no impact to the environment.”

Ms Madamba said insects have a high feed conversion efficiency because they are cold-blooded.

Feed-to-meat conversion rates (how much feed is needed to produce a kilogramme increase in weight) vary widely depending on the class of the animal and the production practices used.

“On average, insects can convert 2 kg of feed into 1 kg of insect mass, whereas cattle require 8 kg of feed to produce 1 kg of body weight gain,” said Ms Madamba.

Insects can feed on bio-waste, such as food and human waste, compost, and animal slurry, and can transform this into high-quality protein that can be used for animal feed.

Ms Madamba said edible insects are a good source of protein, fatty acids, vitamins, and minerals, though the nutritional profile can vary widely among species.

“This makes them a potential food source for healthy human diets. The same aspects make them a nutritionally beneficial and sustainable source of feed for animals,” she said.

Ms Madamba said while insect consumption by humans has been traditionally practised in various countries over generations, it represents a common dietary component of various animal species such as birds, fish, and mammals, farming of insects for human food and animal feed.

She said production of this “mini-livestock” brings with it several potential benefits and challenges.

“A common misconception of insects as food is that they are only consumed in times of hunger. However, in most instances where they are a staple in local diets, insects are consumed because of their taste, and not because there are no other food sources available,” said Ms Madamba.

“Certain insect species, such as mopane caterpillars in Zimbabwe and most countries in southern Africa and weaver ant eggs in Southeast Asia, can fetch high prices and are hailed as delicacies.”

Ms Madamba said it has been scientifically proven that there are no known cases of transmission of diseases or parasitoids to humans from the consumption of insects on the condition that the insects were handled under the same sanitary conditions as any other food.

She said entomophagy (the consumption of insects by humans) is practised in many countries around the world, but predominantly in parts of Asia, Africa and Latin America.

Zimbabwe is among the societies which pride themselves of ethno-entomology because of its long-standing interaction between people and insects through agricultural practices.

“Entomophagy in Zimbabwe is a known established practice, but questions arise as to the details of its practice and its survival among modern technologies hence the need for repositories like the Bulawayo Natural History Museum to carry evidence spanning decades,’ said Ms Madamba.

“Entomophagy is a practice that has been around for a very long time. One may infer the “flying ant” drawing observed on rock art in Matopos World Heritage Site’s Silozwane cave as evidence for the prevalence of the practice among the hunter-gatherer communities in the Stone Age era.”

According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), insects supplement the diets of approximately 2 billion people and have always been a part of human diets.

More than 1 900 edible insect species are consumed around the world. However, this number continues to grow as more research is conducted. The majority of these known species are harvested in the wild.

“This is where researchers and scientists like myself come in identifying what those insects are, what their biology is like, what they feed on, their habitat, and also how we can recreate that environment for farming micro livestock so that it can become an industry that can supply that protein,” said Ms Madamba.

She said in her capacity as a taxonomist, they offer the verification of taxonomy.

“There are so many different kinds of insects and we don’t want people to pick the wrong ones and eat. That is what this whole edible insect research and industry is all about,” said Ms Madamba.

“We are saying it is possible for us to have an alternative to beef or chicken, which is more sustainable that can save the environment in the process. For example, the amount of time it takes to grow a cow and produce a gramme of beef, and then the amount of labour, human resources, and everything that it takes to grow a cow for one meal of a gramme of beef is a lot more than if people focused on micro-livestock.”

Ms Madamba said insects can be grown at homes or aquariums the same way people keep fish.

“We also look at the historical ethnozoological aspect and this is where natural history comes in like what information we have about the insects from the past that can inform what can be done in the future, and also just the historical aspect of usage and how people have cooked them in the past,” she said.

Mopane worms

Ms Madamba said they also collaborate with people who go into the nutrition side of things to get in-depth on what people are getting out of the insects.

She said in her paper, there is information on the different indigenous names of the edible species.

“The intention is for us to then go and visit those places and have a more recent update in terms of collections. We are in the process of looking for funding partners who will take us to those places where we recorded them so that we go and check whether they are still there and what is happening in terms of the environment,” said Ms Madamba.

“From my research, I tried to use the resources we had to gather that information on what this particular species is called in the English, Ndebele, and Shona languages and that is part of the information you are likely to find in that paper.”

Ms Madamba said they are also in the process of documenting information on how edible insects can be identified.

She said while they are relying on indigenous knowledge passed on from generation to generation, they have established that there is an interaction between culture, traditions, and science.

“Part of what we are interested in doing if we get the right kind of traction going is to actually have a feedback mechanism where people can contact us and tell us what they know so that we document these things and be able to pass them on,” said Ms Madamba.

She said for every handful of crickets, the composition of proteins and essential oils and all the nutritional components against that of beef or chicken, the insects would come up tops for the same amount.

“There are papers that have been done by food nutritionists. You have a low production cost and less space and damage to the environment yet there is more nutritional value,” said Ms Madamba.

She said the most common insect delicacies in Zimbabwe are mopane worms with the culture of eating them widespread throughout the country.

inhlwa/ishwa

“The other commonly understood insects such as termites or inhlwa/ishwa, grasshoppers (amaqhagwe) and they are more widely consumed across the board. There is one that is particularly restricted to a small area around Masvingo and Birchenough Bridge that is called harurwa,” said Ms Madamba.

“However, in the Matabeleland region, harurwa/umtshiphela (edible stink bug) is not consumed and I actually did a survey around the Matopos area.

There is also makurwe and it takes a lot of effort to go and check where they would have made their nest, and then you have to dig and catch them.”

Ms Madamba said some delicacies include msasa worms with different scientific names and a lot of species of grasshoppers and beetles that are also edible. She said a curator part of her work involves communicating about the heritage.

“The collections that we have are also a good resource for scientists who come in and literally match whatever specimen they have with what we have.

There are also identification keys that have been made in the past which are the main scientific way to verify them under microscope,” said Ms Madamba.

She said while there are different ways of gathering these edible insects, the first port of call is to actually know about them in terms of seasons.

Ms Madamba said in terms of storage and based on her study, most of them can be boiled, salted and dried.

Comments