Coloniality perpetuates African poverty

Joram Nyathi Spectrum

Coloniality is a concept said to have been advanced mostly by one Anibal Quijano to explain the legacy and damage caused to colonised peoples by their long experience of colonial subjugation. The colonised people were categorised as inferior. In time this was internalised to a point where we the victims of colonialism have accepted that hierarchical order as an immutable law of nature.

Post-colonial rule, for some countries as long as 60 years now, social relations, political authority and economic power still remain what they were during colonial rule, a reality of relations between blacks and whites which cannot be challenged. The whiteman is superior, the blackman is inferior, the blackman is poor, the whiteman is rich, the whiteman must own a farm by right, the blackman can only be a labourer, not even a worker. That is the order of nature.

The colonisers proceeded to fashion laws to entrench for purposes of enforcement social, political and economic structures which they had deliberately invented by dint of colonial conquest. So it is that many years after colonial rule, we maintain structures by ourselves. The whiteman is the yardstick by which we daily judge our interactions — what is good and what is bad, what is correct and what is wrong, what is beautiful and what is ugly, bad practices and good (international best) practices, what to worship and what pagan, what to wear and what to look like to be called civilised, to be savvy.

He comes up with conventions which serve his interests, to which we must subscribe because we can’t be trusted to govern our own lives. The blackman’s mode of thinking, of seeing and interpreting reality, is a product of his stereotyping by the colonial master.

Coloniality is a broad concept, one concept that can help the blackman to liberate, to free himself from colonial rule of the mind, the spirit and the soul, to exorcise the dead weight of colonial culture, mental slavery and the worship of that which blinds him to the reality of Africa’s seeming endless poverty amidst plenty. In short, we need a new mirror to look at post-colonial reality and ask ourselves why independence has not delivered the promise. Whether we ever moved out of the shadow of colonial rule.

There is a huge difference of course between colonialism and coloniality. Under colonialism we are conquered and are not free. Under coloniality, we have conquered but refuse to be free. Under the former, the coloniser is the problem; under coloniality, we are the problem because we have taken it upon ourselves to defend and perpetuate the legacy of colonial inequalities and their rationalisation. The illogicality is the essence of understanding coloniality.

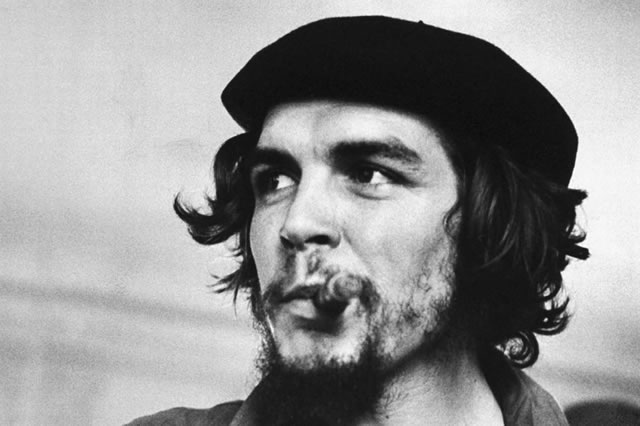

It explains why those who purport to revere third world revolutionaries such as Che Guevara, Sankara, Lumumba, Fanon, Machel, Nkrumah and Nyerere resort to pettifogging about Mugabe’s indigenisation and black economic policies such as the land reform because they can’t challenge the overarching principle — the correctness of resource nationalism. We face a difficulty when it comes to translating the ideals of those heroes were fighting for into a new material reality for liberated Africans.

There is always a gulf between theory and practice, and there are many unforeseeable perils for those who venture into these uncharted waters.

Africa needs a paradigm shift based on principle, what is good, enduring for the continent. The road to development cannot be paved at the whims of those who benefit from its underdevelopment who view it not only as a major source of raw materials but also a huge consumer market for their finished products.

Criticism of colonial rule must not be a refuge for Africa’s failures, but rather a creative process, a stepping stone to self-discovery by the blackman, to a redefinition of the self, a full realisation that the struggle for freedom is far from over.

While the former coloniser is physically gone, he remains happily resident in the mind, in the culture and in our self-definition. He remains a reference point for goodness, democracy, rule of law, constitutionalism, property rights, yes, property acquired through colonial theft by military conquest and legalised by land apportionment instruments which condemned the indigenous peoples to perpetual servitude and poverty. That’s hard truth.

Sadly, it is us the free who rationalise maintenance of the status quo ante to show that we have seen the light, that we are civilised, that we have abandoned our pagan mind and can be trusted to take good care of the whiteman’s property long after he left our dark shores.

Coloniality finds plausible justifications for it all. We are the cause of our poverty — we the victims of rape. Africa remains poor because we are lazy, we can’t think, we are corrupt, we can’t manage the whiteman’s economy, we can’t farm. We repeat these insults to ourselves.

It is heresy to point out the injustices of skewed colonial property rights which must be changed, with guns if necessary; it is a sin to point at the exploitative relationship between the former colonial power and the newly-independent African state. If you are an African you are condemned for demanding an overhaul of those skewed relations, which continue to benefit a former colonial power, already far ahead in development terms, but demands to be treated as if it were the former slave.

Africa just has to take a stand. There is a need for new terms of engagement with Europe. That is possible if Africans are prepared to be cleansed of the demon of coloniality, are ready to move the centre of the universe from Europe to Africa.

It is not enough to condemn the Berlin Conference of 1884-5 and the subsequent scramble for the partition of Africa. The solution to the African condition lies in looking at Africans, changing the self and doing what needs to be done as a continent of independent states. Africa cannot be the one apologising for being colonised and seeking the blessings of the coloniser to develop itself. They say freedom can never be given on a platter.

Africa doesn’t have to apologise for reclaiming what was stolen during the scramble for Africa. Having reclaimed what is due to it, the next step is to add value through learning and sacrifice.

I recently wrote two articles in this column, one in which I said our MPs should use their parliamentary loan scheme to purchase vehicles from Willowvale Mazda Motor Industries for it to grow, and to save scarce foreign currency. I later had an encounter with an MP who told me they had attacked me as MPs for suggesting they purchase low-quality vehicles from WMMI when Cabinet ministers were driving Mercs and Land Rovers.

The second article related to the same matter. A local weekly accused WMMI of assembling poor-quality vehicles and lack of variety. In any case, it noted, they had since stopped assembling vehicles because it was uneconomic to imports kits.

It was cheaper to import from Japan.

In both instances those who accosted me appeared to miss my argument. We are victims of too much exposure and addiction to consumption. My argument was about principle — it’s better to produce than to import, to save than to borrow. It is like choosing between adopting a child and investing in your own wife and waiting for nine months.

These are principles which apply to the whole idea of Africa’s development. We refuse to save; we prefer to borrow. We allow investors to dictate terms and where they invest. But it is evident that foreign direct investment without government control has not improved the lot of the African people.

Recent reports of illicit financial flows from Africa of over $50 billion annually, the equivalent of official foreign assistance, make sad reading. This is in addition to what they take legally. And shows why African governments must play a key role in the ownership of natural resources and choosing priority areas for investment and how proceeds should be shared.

The free for all, laissez faire approach, has failed Africa, and we are to blame because after political independence we have allowed former colonisers to continue to dictate how we should fashion our destiny. It simply hasn’t and won’t work.

These are the basics which should exercise our leaders’ minds as the continent subtracts days towards Agenda 2063. That journey shouldn’t take us to where we were in 1963, 100 years on.

Comments