Combating Africa’s inequalities

Ernest Harsch

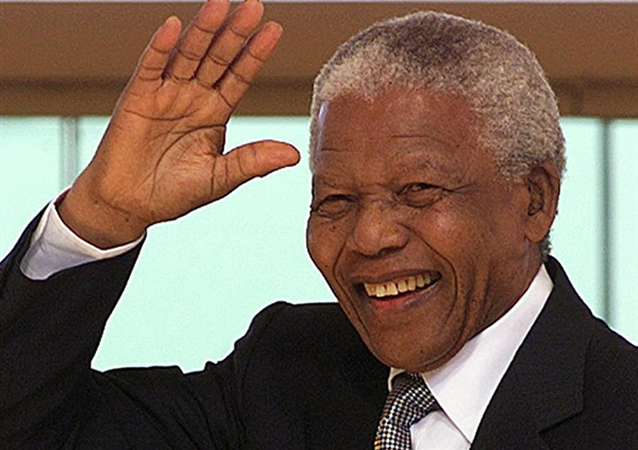

Nelson Mandela, shortly after becoming the first democratically elected president of South Africa, spoke to both his countrymen and women — indeed, for Africans everywhere — when he declared, “We must work together to ensure the equitable distribution of wealth, opportunity and power in our society.”

As he spoke those words in 1996, South Africa was just emerging from a racist apartheid past in which non-whites, more than three-quarters of the population, were not only denied the vote but also denied land ownership, skilled jobs, and most basic services.

The country’s poverty rate, after a brief decline, has been on the rebound since 2015. While millions of South Africans have improved their educational and job prospects, overall income inequality in the country remains stubbornly entrenched.

According to a new study by the UN Development Programme (UNDP), South Africa has the highest recorded level of income inequality in the world. And in this, South Africa is not unusual among African nations. Of the 19 most unequal countries in the world, 10 are in Africa, according to the UNDP’s Income Inequality Trends in sub-Saharan Africa, a report released in New York during the opening week of the UN General Assembly this past September.

While many countries in the region, such as Cote d’Ivoire, Mauritius and Rwanda have registered remarkable economic performance over the past decade and a half, lifting millions out of extreme poverty and making schooling and health care available to larger shares of their populations, others have lagged.

One obstacle to higher incomes for all has been the region’s entrenched economic and social inequalities. The contrast between the visible wealth of elites and the daily misery of most ordinary people makes the disparities seem unjust, driving popular anger and contributing to protest and rebellion.

As President Hage Geingob of Namibia — a country that inherited the highest levels of income inequality in Africa when it gained independence from apartheid-era South Africa in 1990 — told the UN General Assembly, “As long as the wealth of the country is disproportionately in the hands of a few, we cannot have lasting peace and stability.”

Radical shift

Until recently, income inequality received only sporadic attention from development practitioners and policy makers. Before the 1990s they focused mainly on stimulating economic growth. It eventually became clearer that growing markets alone does not necessarily benefit the poor and that excessive liberalisation can in fact hurt them.

When the international community adopted the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 2000, their focus shifted more towards anti-poverty measures and improvements in social well-being.

Poverty subsequently fell in many African countries experiencing economic growth. Yet despite generally robust growth, nearly half the continent’s people still live on less than $1.25 a day. Studies have shown that where there is less inequality, the benefits of growth reach wider sectors of the population. In more unequal nations, however, the rich garner the biggest share and the poor get little.

That realisation underlay the 2015 negotiations over the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The global goals call not only for ending poverty, but also for reducing inequalities within and among nations. The UNDP terms this a “radical shift” intended to address the “last mile of exclusion” that prevents many people from improving their lives.

In analysing income inequality in Africa, the UNDP report focuses on 29 sub-Saharan countries (which account for 80% of Africa’s population) for which there is adequate data on household consumption. It shows that between 1991 and 2011, 17 of those countries managed to reduce their degree of income inequality. But the remaining dozen registered an increase in income inequality over the same period.

That divergence reflects the historical, economic, social and political factors affecting income inequality in each country.

Countries with higher — and rising — income inequality are mainly in Southern and Central Africa; they have capital-intensive oil and mining sectors with limited employment or are former settler societies that still have large landholdings.

Countries with declining income inequality, most of which are in West Africa, generally started out with lower levels of inequality and have predominantly smallholder agricultural sectors in which many people stand to benefit from improvements in productivity.

Income inequalities in different countries differ by degree, but the more important distinction is the factors that shape them. The root causes of inequality are rarely the same from country to country and may include restricted access to land, capital and markets; inequitable tax systems; excessive vulnerability to unfavourable global markets; rampant corruption; and the patrimonial allocation of public resources.

Although gender inequalities exist in all countries and are particularly severe in Africa, they are generally underestimated in most standard measures, which rely on household income or consumption data. Such estimates tend to assume equal spending powers among all family members.

While some countries have seen efforts to reduce economic disparities, others have been marked by opposition to such efforts by “incumbent elites,” according to researchers cited in the report.

The marginalisation of certain geographical regions or the social and political exclusion of minority ethnic and religious groups can bring especially explosive consequences, the new UNDP report says, contributing to unrest and even armed conflict.

No single solution

Because of the complex, multidimensional factors influencing inequality, “There is no one ‘silver bullet’ to address its challenge,” observes Abdoulaye Mar Dieye, UNDP’s assistant administrator and director of its Africa bureau. “Multiple responses are required.”

Whatever a country’s specific history and circumstances, a number of measures have proven especially fruitful in reducing inequalities across the region: increasing productivity among small-scale farmers, ensuring women’s access to land, reversing urban favouritism in services and economic opportunities, promoting labour-intensive industries, setting minimum wages, strengthening capacities to keep the wealthy from evading taxes, introducing strong social protection programmes and ending all forms of exclusion.

Ultimately, such efforts are intended to ensure that all Africans are able to live productive and fulfilling lives and to uphold the SDGs’ pledge to “leave no one behind.” — Africa Renewal.

Comments