Four months of fear at Dr Nkomo’s rural home

Mashudu Netsianda, Senior Reporter

THE late Vice-President Dr Joshua Mqabuko Nkomo’s nephew, Mr Thomas Sihle Nkomo (82) witnessed the restriction of the nationalist to his brother’s homestead in Kezi in Matobo District, with Rhodesian forces pitching camp in the area to intimidate villagers.

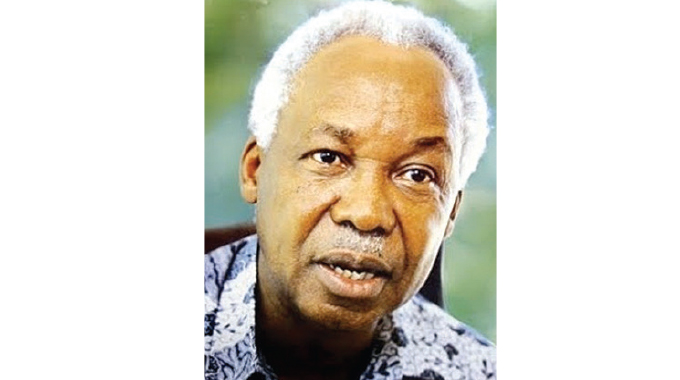

The late Dr Joshua Mqabuko Nkomo

A Chronicle news crew on Tuesday visited the Nkomo homestead and spoke to Mr Nkomo, about the drama he saw unfold 60 years ago.

Popularly known as Father Zimbabwe, the fearless freedom fighter, had just returned home from exile in September 1962 when Rhodesian security agents intercepted him, minutes after landing at the then Salisbury International Airport (Robert Gabriel Mugabe International Airport) in Harare.

He was subsequently bundled into a police car and taken on a long road trip to Bulawayo. He was detained at Bulawayo Central Police Station before being transferred to Kezi Police Station and later to his homestead where he spent four months under a restriction order.

Dr Nkomo succumbed to prostate cancer on July 1, 1999 at the age of 82, and was buried at the National Heroes Acre in Harare.

He used trade unionism as a stepping stone to politics to oppose white settler domination in southern Rhodesia.

Dr Nkomo was in Lusaka when Zapu was banned in 1962. After some days of thought, he came to the conclusion that the time had passed when anything useful could be achieved by the party within Southern Rhodesia.

Two of his parties, the National Democratic Party (NDP) and Zapu, had been banned, and their assets confiscated, within nine months. Any further creations would, he believed, be similarly handled.

The answer, he concluded, lay in setting up a ‘government in-exile’ which, by freely bringing pressure to bear on the UN, the Organisation of Africa Unity (OAU) and other sympathetic bodies, would stimulate international action to effect political change at home.

Dr Nkomo called a meeting of the executive in Dar-es-Salaam to discuss the matter.

Dr Julius Nyerere

On arrival there, he came under strong pressure from Rev Ndabaningi Sithole, Enoch Dumbutshena and Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere, all of whom felt that he should return to Salisbury (Harare) and suffer the same restraints as the other leaders.

Dr Nkomo followed this advice, and on his arrival back in Southern Rhodesia, he was restricted for four months to Kezi.

In an interview, Mr Nkomo who was named after his grandfather, Dr Nkomo’s father, Thomas Nyongolo Letswana Nkomo said his paternal uncle arrived at their homestead in a Rhodesian police Land Rover with a convoy of several military Jeeps in tow.

“I vividly recall the day in September 1962 when my uncle, Dr Joshua Mqabuko Nkomo was brought home in a police Land Rover with a convoy of military Jeeps following behind.

When the Rhodesia security agents arrived at our homestead in a convoy of military Jeeps, my father (Dr Nkomo’s brother) had gone to the bush to look for his donkeys,” he said.

“There was my mother and us children at home. My mother was visibly shaken upon sight of the police and soldiers invading our homestead with my uncle (Dr Nkomo).”

Mr Nkomo said his mother trembled as she asked Dr Nkomo why armed police had brought him home in a convoy.

“Dr Nkomo replied by simply saying ‘You should not worry everything is under control’. He then went to tell my mother that Zapu had been banned and that he was placed under restriction by virtue of being its leader,” he said.

“My father later arrived and asked his younger brother (Dr Nkomo) as to what was happening in his homestead and he said exactly what he had told my mother.”

Mr Nkomo said fear gripped the entire Nkomo family as they witnessed the drama unfold with more police officers and soldiers continuously arriving in their camouflaged Jeeps and Land Rovers.

“They disembarked from their vehicles and immediately started offloading their bags and pitched tents around our homestead. It was so scary and everyone was terrified, but surprisingly as all that was happening Dr Nkomo was unfazed as he silently watched the spectacle,” he said

Mr Nkomo said since his uncle didn’t have his own homestead at the time, his brother, Sihle accommodated him in his thatched hut while the local community built him a house at the same compound.

“Dr Nkomo stayed at our homestead throughout his entire restriction order, which he served from September to December in 1962.

He was only allowed to move out of the homestead for a radius of not more than 3km under police escort,” he said.

During that period, Mr Nkomo who was 23 years old, said they lived in fear with constant gunshots being fired by Rhodesian security agents to instill fear in the family.

Zapu-PF

At first, party loyalists including the Zapu leadership were afraid of visiting Dr Nkomo in apparent fear of the Rhodesian security agents who had camped outside the homestead.

“Later, people realised that shunning Dr Nkomo defeated the whole purpose of the struggle.

They started visiting him at our homestead and some of the people that I still remember coming to our home include the likes of Cde Joseph Msika, Cde Lazarus Nkala and former Southern Rhodesia Prime Minister Sir Garfield Todd among other nationalists who had also been previously served with restriction orders,” said Mr Nkomo.

“Although police tried to intimidate people who were coming to visit Dr Nkomo, it didn’t work because people were determined and prepared to face the consequences. As a family, that fear which had gripped us gradually disappeared as we eventually got accustomed to the heavy presence of police and soldiers around our homestead.”

Mr Nkomo said throughout his restriction, the undeterred Dr Nkomo exhibited bravery, zeal and determination to liberate the country from the repressive colonial government.

During detention, his wife, Johanna MaFuyana Nkomo and their children were under the custody of missionaries at Empandeni Mission, one of the country’s oldest surviving Catholic missions in Mangwe district.

“The Rhodesian government didn’t know that by restricting Dr Nkomo to his village, they were in a way giving him an opportunity to also interact with people at grassroots level and mobilising them to take up arms against the colonial regime,” he said.

“We stayed with Dr Nkomo for four months until December when the restriction order was revoked with the security agents leaving our homestead.”

Mr Nkomo said upon the revocation of the restriction order, there was tremendous joy and a party was thrown to celebrate Dr Nkomo’s freedom. He said Dr Nkomo left Kezi on January 3, 1963.

However, Dr Nkomo had not abandoned his belief that the nationalist cause could best be furthered at that stage by activity from outside the country.

United Nations headquarters in New York

Upon his release from restriction he travelled to New York, where he addressed the UN Committee on March 23, 1963.

On April 16, 1964, Dr Nkomo was arrested, detained and spent the next 10 years at the notorious Gonakudzingwa Detention Camp.

Mr Nkomo said his father, Sihle Nkomo was later arrested in 1966 and detained for three years at Gonakudzingwa Camp 3 while Dr Nkomo was at another camp.

On his release in 1974, Dr Nkomo left the country to lead the armed liberation war, using Zambia as the base of the Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army (ZPRA), which he led as its commander-in-chief

Mr Nkomo said Dr Nkomo grew up in the village herding cattle near Semukwe River during which he displayed astute leadership qualities in his daily interactions with his peers.

“As a boy, he loved experimenting a lot and at one time he built a house in the tree top. His peers were amazed at his creative imagination, which shows how intelligent he was at a tender age,” said Mr Nkomo.

He urged the Government to develop Kezi due to its historic significance.

“We have a major challenge of water and children walk long distances to school while the nearest clinic at St Joseph Mission, is about 10km away,” said Mr Nkomo.

He said Dr Nkomo had a long term vision to transform his homestead into a clinic to cater for the local community.

“I am 82 years old now, but sadly I am forced to walk a distance of about 20km to and from St Joseph Mission Clinic,” said Mr Nkomo.

Comments