June 16 − A day for sober reflection on plight of the African Child

Cuthbert Mavheko

Zimbabwe tomorrow joins other member states of the African Union (AU) in commemorating the Day of The African Child.

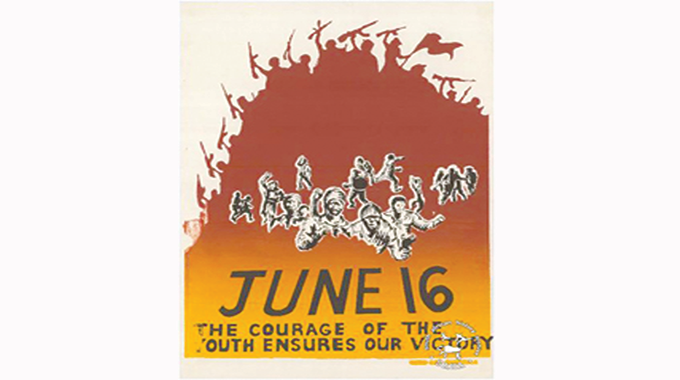

The continent-wide holiday honours black South African students who participated in the Soweto Uprising of 1976.

On June 16, 1976 more than 10 000 black students from Soweto in South Africa took to the streets to protest against the Black Education Act, which segregated students on racial lines.

In the two weeks of protests that followed, more than a 100 students were shot dead by security forces while thousands were badly injured.

The Day of the African Child was instituted in 1991 by the Assembly of Heads of State and Government of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in memory of the June 16, 1976 students uprising in Soweto.

Since then, the OAU and its successor the AU have used the day to celebrate children in Africa and to inspire among the people a sober reflection and action towards improving their education.

Although significant progress has been made in the education sector since the Soweto Uprising, it is estimated that one in 10 children do not attend school in South Africa. More still needs to be done to ensure that all children, whether black or white, receive quality education.

According to some reports, of the 57 million primary school-age children not attending school around the world, over half of them are from sub-Saharan Africa.

It is no hidden secret that poverty is making it increasingly difficult for most parents in Zimbabwe to educate their children. According to some reports, approximately 72 percent of Zimbabweans are languishing in the throes of chronic poverty. Eighty four percent of them live in rural areas while 38,2 percent reside in urban areas. Some surveys say there are more children not attending school in rural areas than in urban areas.

To mitigate the effects of poverty, some parents are being forced to marry off their children at a tender age so that they use the bride price (lobola) to sustain their families.

Child marriage is not a phenomenon that is typical to Africa alone; it is a global problem. There is no country, religion or culture which is immune from it. Worldwide, nearly 12 million girls are married before they attain the age of 18.

In terms of numbers, India has the highest number of children who marry at a very tender age. The rate of child marriage in that country is 47 percent. Niger, Chad, Mali and the Central African Republic have the highest rates of child marriage on the African continent, with more than 50 percent of girls getting married by 18.

A survey by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) revealed that 32 percent of girls in Zimbabwe under the age of 18 are in forced marriages, with 15 percent of them getting married at the age of 15.

According to Ms Nomusa Mtetwa, an activist who champions the rights of the Girl Child, society is entirely to blame for pushing children into early marriages.

“In Zimbabwe, child marriage is driven by poverty, cultural norms and various other social and economic practices. Girls are often married off at an early age to reduce their perceived economic burden on the family, with the bride price (lobola) being used to sustain the family.

“Girls from poor families are more likely to get married before the age of 18 than those from wealthy families. Religion also contributes to child marriages. In Zimbabwe we have a situation where some indigenous Apostolic Churches compel young girls to get married to men old enough to be their grandfathers in order to receive “spiritual guidance,” she said.

It is therefore heartening to note that Zimbabwe has committed itself to eliminate early child marriages in line with target 5.3 of the Sustainable Development goals. During its Voluntary National Review at the 2017 High Level Political Forum, the Government re-affirmed its commitment to the target, highlighting that the Constitutional Court in 2016 outlawed the marriage of people under the age of 18.

In June 2016, the Constitutional Court of Zimbabwe ruled that the Marriage Act, which permitted girls as young as 16 to be married with the consent of their parents, was unconstitutional and recognised 18 years as the legal age of marriage.

It is important to note that this ruling includes marriages under the Customary Marriages Act, which had previously not had a minimum age requirement.

In 1990, Zimbabwe ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which sets the minimum age of marriage of 18.The country also acceded to the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women, which compels states to ensure free and full consent to marriage.

In 2016, the UN Child Rights Committee urged Zimbabwe to implement an effective monitoring system to assess progress towards ending child marriage in the country. The Committee also asked Government to provide victims of child marriage with compensation and rehabilitation. The Committee also asked the Government to conduct investigations into the alleged involvement of members of some religious sects in facilitating child marriages.

According to health experts, early marriage has adverse ramifications on the health of the girl child.

“Due to the fact that the girl child’s body is not adequately developed to conceive and bear a child, there are bound to be complications during pregnancy and child birth. In fact, statistics show that early pregnancy and child birth are the leading cause of death among 15 to 19 year-old girls the world over. Early marriage also increases the risk of HIV infection in girls,” said Dr Stanford Mutangadura, a gynecologist.

He said the adverse effects of early marriage go beyond the lives of the young married girls themselves and ultimately affect the next generation.

“Girls who enter into early marriages are often forced to drop out of school. Apart from diminishing the girl child’s future prospects, child marriage also limits her ability to contribute meaningfully to her country’s socio-economic evolution.

“Over and above this, children of young, uneducated mothers are less likely to have a good start to their education, to do well in class or to proceed with education beyond the minimum level of schooling. To rub salt to injury, daughters of uneducated mothers are very likely to also drop out of school like their mothers and continue the vicious cycle,” he said.

It has been proven that education has tremendous transformative powers. For with a sound education, children, especially girls, are more likely to stay healthy, be more independent and become a force for social change.

It is the humble submission of this pen that if African children left school equipped with basic reading and writing skills, millions of them could be bailed out of the morass of searing illiteracy.

-Cuthbert Mavheko is a freelance journalist based in Bulawayo. He can be contacted via mobile 0773 963 448 or e-mail [email protected]

Comments