Go well mfo kaMzombi!

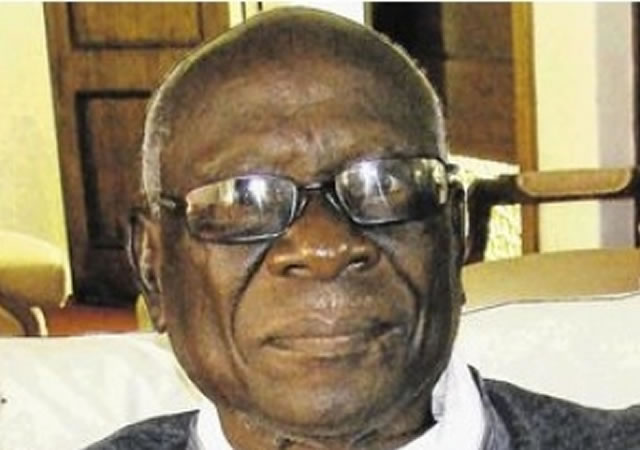

Saul Gwakuba Ndlovu

The death of Enos Nkala virtually brings to an end the number of people of Ndebele extraction who played a senior role in the founding and running of the Zimbabwe African National Union (Zanu).The first to die a few years ago was Mark Nuda Dube who was a senior Zanla commander during the liberation war, and was later appointed Matabeleland South provincial governor.

The author of this article first met Enos Nkala briefly at Cyril Jennings Hall in Harare’s (then Salisbury) socially and politically pulsating Highfield suburb towards the end of 1960 or thereabouts.

The National Democratic Party (NDP) was at the climax of its revolutionary influence, and Enos Nkala, a senior official of its national executive, was popularly referred to as the “Lion of Sinoia”, today’s Chinhoyi. No sooner had I met him than he was arrested and convicted for making what the white minority settler regime regarded as a subversive statement at a rally in Chinhoyi.

He was jailed for a couple of years and was released in about 1963 shortly after the Rhodesian Front (RF) had replaced the United Federal Party (UFP) of Sir Edgar Whitehead as the government. The RF was at that time led by Winston Joseph Field, a Marondera-based tobacco farmer.

By then I was a full time newspaper journalist and was bound to interact with Nkala very much. Our interpersonal relationship became quite amiable because I had some years earlier studied and lived with two of his clan brothers, Luke and Leonard and their sister, Thandiwe (later Mrs Bhebe) at Inyathi. They were as close to me as my brothers, so did Enos become in Salisbury.

That apart, I noticed two rather unique characteristics in him. He was first and foremost courage personified. Whenever there was cause for the police to come, sirens wailing, Enos would approach them while everyone else was scampering and looking for holes to hide in, and interact with them with a great deal of composure.

The other characteristic I noticed in him was that he was not worried about being involved in controversy. In fact on some occasions he courted controversy as was the case during Gukurahundi.

It was basically because of those two strengths that he joined the anti-Joshua Nkomo group in 1963. He was released from prison when Zimbabwe’s African nationalist political activity seemed to have been paralysed by the ban of Zapu.

We did not know what would take place. A decision to defy the ban had been duly taken earlier. Zapu would go underground and continue the struggle. But nothing seemed to be happening.

John Maluzo Ndlovu, Amen Chikwakwata and a couple of other activists had been arrested for petrol bombing the Salisbury-Umtali mail train. So what? Joshua Nkomo had been released from restriction and so were others, including the fiery James Robert Dambaza Chikerema, the irreversible George “Bonzo” Nyandoro, the highly committed Daniel Madzimbamuto, and the taciturn Maurice Nyagumbo, not to leave out the studious Eddison Sithole.

Was Nkomo going to form a government-in-exile based in Dar-es-Salaam, thousands of kilometres away? A precedent had been created by Holden Roberto of Angola whose government-in-exile was based in Morocco, a 72-hour non-stop flight (at that time of the Dakotas) from Leopoldville (now Kinshasa) where Roberto’s nearest office to Angola was located.

Another precedent was the Second World War Polish London-based government-in-exile, those who supported that idea argued. The issue was quite topical in Harare.

But the whole idea seemed to be nothing more than just that, an idea. Nkomo had never officially mentioned it or commented on it. In any case, Roberto’s administration-in-exile had no effect whatsoever on the Angolan liberation struggle.

As for the Polish experience, Britain and its empire and the Commonwealth had been ferociously fighting Germany precisely because the latter invaded Poland, and, secondly, because Polish exiles had several brigades on the field during the Second World War.

But we seemed to be waiting for something for which we had not prepared: underground operations. It was in that atmosphere that a very determined anti-Nkomo leadership group emerged and Enos Nkala was a part of it. The initial idea was to replace Nkomo as the top black national leader.

However, that was abandoned following a very violent countrywide campaign headed by Chikerema. Criticism against Nkomo ranged from the absurd to the malicious. In an editorial comment, one old black journalist whose political sympathies lay with Sir Edgar Whitehead’s UFP said many people who supported Nkomo did not seem to notice that he (Nkomo) resembled the late Ndebele King, Lobengula, and that if he were to rule Zimbabwe, he would be as ruthless as Lobengula.

Some moralists claimed that he was most immoral because he had girl friends in every town and village from Plumtree to Mutare and from Victoria Falls to Beitbridge. Yet some described him as spineless and not dynamic.

The opinion of the author of this article was that Joshua Nkomo detested bloodshed and massive destruction of property. It was also this author’s opinion that many of those who criticised Nkomo had been an integral part of his successive organisations and could have made him more dynamic themselves.

Enos Nkala felt that Nkomo hoped against reality that the British government would sooner rather than later convene an independence constitution on Zimbabwe.

“We need a committee and irreversible leadership to liberate this country, and we will announce to the world that leadership at my house on August 8,” said Nkala to this writer a day or two before the historic event.

I had gone to him to try and persuade him to withdraw his support from that group because my practical experience on the group at that time was that Joshua Nkomo commanded overwhelming support throughout the country with the exception of a tiny vociferous clique from Zaka in the Fort Victoria District (now Masvingo) who always swore that they would “never be ruled by a re-incarnation of Robhengura!”

Each time a Nkomo-led political party was banned they formed one of their own ranging from the Zimbabwe National Party (ZNP) to something called African Socialist Union. A prominent member of that group was the comical Patrick Gonese. He died in Zambia years later.

My conclusion on that fateful day at Enos Nkala’s house was that the die was cast and that Nkomo and those loyal to him had to pull up their socks. Enos Nkala said Ndabaningi Sithole would lead the new party. I knew Sithole well. He had been my teacher at Tegwane (now Thekwane) when that institution’s principal was the Rev G E Hay-Pluke. Sithole was serious-minded.

He said Sithole would be deputised by Leopold Takawira, a former school head. Takawira had deeply influenced me at Cyril Jennings Hall one day when he heard me sympathising with one activist, Malachi Mandimutsa for having spent a stint in prison for a political offence.

“Saul, going to jail is an inevitable price you and I and him have to pay to free our country. So don’t be sorry but be happy that Malachi is a courageous cadre,” he said most firmly.

I left Enos Nkala’s house with a question for which I have no answer up to now. It was (and is):

“Why was it not possible for the group to inject a sense of urgency such as was shown soon after the Zanu launch by the Crocodile Gang in the Chipinge area while they were still in Zapu? That could have brought the liberation of Zimbabwe much nearer, a wish for which Enos Nkala and others spent years at Sikombela (not Gonakudzingwa as was erroneously reported) and for which bloody clashes between Zanu and Zapu occurred at home and abroad. Go well mfo kaMzombi! Ubuyindoda isibili mfowethu!

Saul Gwakuba Ndlovu is a war veteran and Bulawayo-based retired journalist. He can be contacted on cell 0734328136 or through email [email protected] <mailto:[email protected]>

Comments