Land seizure — the oil-soaked rag . . . and the matchstick that lit the liberation bonfire

Vincent Gono, Features Editor

ITALIAN politician, philosopher and patriot who is credited with giving the Italians the vision of a united Italy, Giuseppe Mazzini once opined that, “The tree of liberty grows stronger when watered by the blood of the martyrs.”

His dream and vision of a united Italy was then taken up, sanctified and made a dream come true by the generation of Cavour the statesman and Garibaldi the soldier.

Bringing history closer home in the month of celebrating the country’s heroes and defence forces, the spectrum stretches far and wide into history from Mbuya Nehanda, Sekuru Kaguvi, Chief Rekayi Tangwena, Chief Mapondera who pioneered resistance and passed the baton to the generation of Benjamin Burombo, Joshua Nkomo, Robert Mugabe, Josiah Tongogara, Herbert Chitepo, Lookout Masuku, Solomon Mujuru, Alfred Nikita Mangena, George Malan Silundika, Joseph Msika, Vitalis Zvinavashe, Josiah Tungamirai, Dumiso Dabengwa and the list goes on and on.

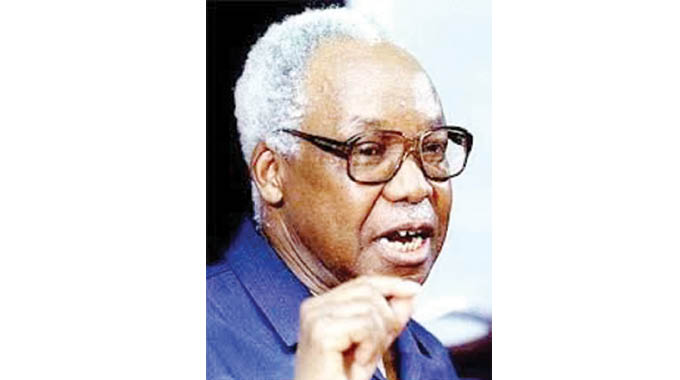

The late Dr Joshua Mqabuko Nkomo

These departed sons and daughters of the soil and others who are still living took up the vision of a liberated country and decided that their blood, sweat and tears should water the tree of liberation which the country enjoys today.

The Heroes and Defence Forces Holidays should therefore be celebrated in memory of the illustrious work done by the heroes both departed and living while also taking stock of the achievements of the objectives of such sacrifices.

It is in the same spirit that the context of the historical narratives and objectives of the liberation struggle should be understood and pertinent questions asked on the political, economic and social development of the country.

The question of land features prominently in the shaping of the liberation struggle and in post- independent Zimbabwe, earning the country both friends and foes in the global political matrix.

Land was the oil-soaked rag and its seizure from the black population provided the matchstick that lit the liberation bonfire. Chief Tangwena is one of many leaders who refused to move out of his ancestral land.

“I am married to this land… I was put here by God and if I am to leave, I must be removed by God who put me here…,” were part of his salutary remarks that showed his appreciation of land as the greatest means of production.

In some parts of the country the black population was moved to reserves that were created while large tracts of the country’s prime land were occupied by the settlers.

Reserves such as the Gwayi and Shangani were established for the black population.

These were rocky and tsetse fly-infested areas where stones grew better than plants and where rainfall rarely visited.

They were not suitable to sustain crop and livestock production and the black population saw it as a place where they were sent to die.

It was therefore the question of land that aggravated the aggression and explains why there was a regional spirit of oneness in fighting imperialism to repossess the looted African resource that was now in the hands of a few white settlers.

The country’s social development and cohesion therefore, has no basis in the availability of money as imperialists and capitalist economists may want us to believe, money was introduced a little later to a society that was never poor because of its unavailability.

It has to do with land.

And Zimbabwe has moved mountains in addressing the land ownership question to ensure productivity.

The land reform remains the biggest achievement and a walk back into the history of the land issue will suffice.

The land reform in Zimbabwe was officially supposed to take effect in 1980 with the signing of the Lancaster House Agreement.

There were marked inequalities in land ownership because of population growth and escalation of poverty in the subsistence areas parallel to the underutilisation of land on commercial farms.

The Lancaster House Agreement provided for the willing buyer, willing seller basis where the British government was to provide the funds but Britain reneged on the agreement in the late 1990s when Prime Minister Tony Blair terminated this arrangement after funds that were availed by the Margaret Thatcher’s administration were exhausted.

He refused all commitments to land reform.

On November 5, 1997, British secretary of state for international development Clare Short, described the new Labour government’s approach to Zimbabwean land reform.

She said that the UK did not accept that Britain had a special responsibility to meet the costs of land purchase in Zimbabwe.

Her government’s position was spelt out in a letter to the then Zimbabwe’s Agriculture Minister, Kumbirai Kangai:

“I should make it clear that we do not accept that Britain has a special responsibility to meet the costs of land purchase in Zimbabwe.

We are a new government from diverse backgrounds without links to former colonial interests.

My own origins are Irish and, as you know, we were colonised, not colonisers.”

After this position was spelt out Zimbabwe responded by embarking on a “fast-track” redistribution campaign, where through the national land policy, Government would acquire land as it saw fit for redistribution to landless Zimbabweans.

The land reform therefore depopulated the country’s communal areas as people moved into formerly white-owned farms. Land ownership ceased to be a racial question that it used to be where a few whites used to own and control large tracts of land.

And in the spirit of transparency, the Government embarked on a land audit to expose corruption and a number of irregularities in the land allocation patterns.

The audit also took stock of how many farms an individual owns, land usage, and size of the farm.

According to President Mnangagwa, this will see a lot of land being repossessed from land barons who hold on to land for speculative purposes for redistribution to other landless citizens.

He said his Government was seized with the issue of ensuring that those who were allocated land were given the proper hectarage, that there was no multiple ownership and that there was proper land usage.

This, he said, was going to be uncovered through a land audit that was done.

And today the chorus of land ownership in Africa is growing louder with regional populations urging their governments to sing from the same land reform stanza with Zimbabwe as the only way to empower their communities and give them the means of production.

The entrepreneurial spirit that Africa was blinded to by colonial education is quickly gaining expression with calls for all systems to be aligned to ensure the destiny of the continent finds residence in its people.

Mwalimu Julius Kambarage Nyerere

The writings of nationalist leaders such as Mwalimu Julius Kambarage Nyerere of Tanzania come into perspective.

Nyerere argued that for development, Africa must first and foremost depend on its local people and its resources.

“It is we, the people of Africa, who experience, in our lives, the meaning of poverty.

It is we, therefore, who can be expected to fight that poverty. Certainly, no one else will do it if we do not.”

The first requirement for development according to Nyerere was therefore not reliance on richer nations and their resources but dependence on the local resources and manpower, a philosophy that has been adopted by President Mnangagwa where local resources are value- added to improve livelihoods of communities.

President Mnangagwa

He prohibited the poor from depending on money as the basis of development.

He objected to this stance arguing that a poor man does not use money as a weapon.

By this, he was suggesting that a poor person who chose money as his “weapon” to get him out of poverty was doomed to failure because he had chosen to fight poverty with a weapon he did not have.

Poverty must be fought with weapons to which Africans could lay claim on and the weapon to fight poverty that most African countries have in abundance is land.

Nyerere argued that money donated in terms of gifts, loans and private investments could not be depended upon for development because in the final analysis they would endanger the freedom and the independence of Africa.

He called on public institutions to be given land, something that has found expression in Zimbabwe where boarding schools, universities, prisons and hospitals own farms although the question is whether the land is being used ideally to produce for those institutions’ self-sustenance and surplus for sale.

Land ownership therefore remains the pillar of Africa’s economic and social development.

Comments