The man who paid with his life protesting declaration of UDI

Jonathan Maphenduka

WHEN Rhodesia leader, Ian Smith announced Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) on November 11 1965, I was covering the trial of three men who faced charges under the Law and Order (Maintenance) Act. The trial was being held at Nyamandlovu Magistrate Court. The allegation was that they contravened sections of the Act by derailing a train near this farming village.

The men faced death or life imprisonment if convicted. They denied the charge. I returned to the office to find in the news room a huge man with golden hair sitting in the news editor’s office. The man was the censorship officer appointed by the regime. His job was to ensure that any news item which tarnished the image of the regime, was to be deleted. The newspaper’s management quickly decided that any censored news item was not to be replaced.

When I returned from my assignment, the news editor (a man named Charles Byford-Jones) was not in his office, apparently at a meeting with the management to consider how the problem of censorship would be handled. It was decided that no censored news item would be replaced. It was a bold step that eventually led to the lifting of censorship and the newspaper returned to its routine.

While censorship remained in force it became common to come out with the newspaper showing white spaces left after an item intended for that space had been removed by the censorship officer.

It became a common feature, therefore, for every edition to come out with white spaces. In the long run it became so embarrassing to the regime that censorship was dropped and the newspaper resumed its normal routine. Censorship had proved such an embarrassment to the regime because it was seen by the international community as an indication that the regime had something sinister to hide from the watching world.

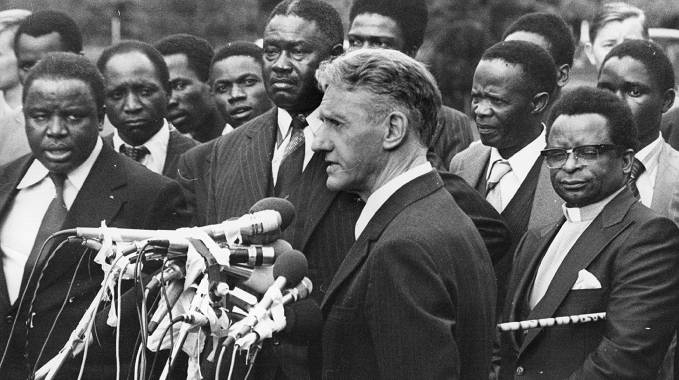

It was two weeks after Ian Smith grabbed independence, during which time African nationalists had been calling on the Labour Party government of Prime Minister Harold Wilson to send troops to crush the rebellion, that the first and only anti-UDI protest was witnessed. Looking back now it becomes clear that the nationalists did not understand or appreciate Great Britain’s foreign policy.

The declaration of independence was for all intents and purposes a kith and kin affair, and Britain has never been known to use gunboat diplomacy against its own people. The exception was Northern Ireland whose citizens were essentially people from Scotland who fled persecution by their English rulers.

On Tuesday, exactly two weeks following UDI, I was off duty and woke up to calls by nationalists for people to stay at home. The first ever anti-UDI demonstration was under way. Still in my dressing gown, I joined a group of demonstrators along nearby Mathonisa Road which was flanked by protesters from east to west.

I found myself in a group of about seven or eight demonstrators on the north side of the road among which, I remember, was Landgard Gumpo and Joel Thebe, both of whom lived nearby. At this time of day Rhodesia Omnibus Company buses should have been trundling up and down picking up people for their work places. This morning, however, no buses were in sight.

Suddenly, one bus appeared from the east, with policemen inside. At this point, however, we did not know that. It was slowly driving past when a muzzle of rifle popped out of a window of the bus and a shot cracked and left Joel Thebe dead. Two policemen, with cocked rifles, alighted and dragged Thebe’s body on to the bus.

When the police came out of the bus, we scurried away to take refuge behind nearby houses.

It could have been my body being dragged away but I think what probably saved my life was that I was still wearing my morning gown and this may have been taken by the police as evidence that I had been dragged away (against my will) to join the protesters.

The shooting marked the end of anti-UDI demonstrations. I hurried back to the house to take my car and drive to the office to report. It had been a peaceful demonstration but the government said protesters had been stoning buses and police had opened fire to protect property and themselves.

How often do governments get away with murder by lying?

However, recruitment of freedom fighters was now under way in both Southern Rhodesia and Northern Rhodesia. Among those who left Kitwe, led by none other than Jacob (Mayihlome) Moyo, was my younger brother Agrippa, who returned home in 1967 to die in the famous Battle of Wankie.

Jacob Moyo had abdicated the Sheleni chieftainship of Mahlabathini, on the northern edge of Matobo District, to join the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) amid great expectations by the country’s people.

Moyo was the leader of young people who left Zambia in 1964 to go for training in guerrilla warfare in Ben Bella’s Algeria, to return home to wage war against the white regime.

While there, they had launched anti-UDI protests during which Moyo lost an eye when Algerian police charged them to quell the protests.

Let me take this privilege to enlighten those readers who may not be familiar with a subject of great interest to the people of Matabeleland. This is the assertion that Cecil John Rhodes “separated two fighting bulls” when on four occasions Rhodes met 28 chiefs in the Matopos theatre of the rising.

Rhodes did nothing of the sort because there was no peace treaty signed, and because of that the United Kingdom is, technically speaking, still in a state of perpetual war with the people of Matabeleland.

Moreover in those four meetings, during which Somabulane was the spokesman for the chiefs, only Nyanda represented the royal family. Even more important is the fact that the warriors emerged from the last meeting with Rhodes in October, still holding their weapons.

Although Rhodes knew that Nyamande had been crowned king to succeed Lobengula, he made no effort to involve the new king in the talks because, as one writer observes, of fear of “complications in future”. These complications are directly linked to the purging of the monarch which soon followed with the removal of Lobengula’s three sons, Njube, Nguboyenja and Mphezeni “to be educated” in Rhodes’ Cape colony.

Moreover there is a great deal of quibbling about Nyamande’s coronation. Another issue is whether the four talks Rhodes held with the chiefs led by Somabulane amounted to a peace treaty. I can state here and now that Rhodes did not sign a peace treaty with anyone who was involved in the 1896 rising.

In war there are three stages that can occur: a truce, an armistice and a treaty. What happened at the Matopos was a truce to initiate peace talks. The position between North Korea and South Korea (for an example) after Vietnam, is an armistice which was created by super powers to maintain a foothold in South East Asia after the Vietcong forced American forces to surrender.

The position between North Korea and South Korea is a state of armistice: with superpower United States standing between them through that demilitarised zone between the two states to prevent a shooting war between the two sides of the same people.

A reader may ask: why did the uprising collapse after that last meeting with Rhodes in October if there was no peace treaty? The answer to this question is that a coalition of Imperial government forces and Rhodes’ own forces, under the command of Edward Carrington launched a scorched earth strategy which left the people without food reserves and livestock in every sector of the rising, from the Matopos to Zhombe (where Mphoko and M’thubani were in command) and from Nyamandlovu to Lalaphansi.

The effect was devastating, with long queues of starving people trying to find their way to Bulawayo where they hoped to find food. That is the short and long of an abject surrender which has no parallel in British colonial history.

In December a general amnesty was declared and King Nyamande (he had been on the list of proscribed warriors) returned to Bulawayo to be deposed and made a senior chief in the District of Bulawayo which he refused to accept. He was then restricted to his rural home in Mbembesi where no chiefs were allowed to visit him.

He became the first political restrictee in the history of British colonialism in this country.

I deal at some length with the issues pertaining Nyamande’s disputed ascension to the throne to succeed Lobengula and the questions relating to the purge of the royal family. I further deal at some length with the hanging questions whether or not Nyamande was a legitimate successor to Lobengula in my new book The Right of Conquest Madness In Matabeleland which was self-published in Antlanta on March 14 and printed by Ingrams USA.

The book is already selling online by Amazon.Com. Its launch in Bulawayo was interrupted by the outbreak of the Covic-19 pandemic. But anyone who wants to find out the truth about the purging of the Matabele Monarchy can read Professor Terence O. Ranger’s book The African Voice in Southern Rhodesia. The book explains how Njube and Nguboyenja were treated after their younger sibling, Mphezeni “drowned” in Port Elizabeth soon after their arrival in the Colony in 1898.

Mphezeni was barely 10 years when the three princes were removed from their own people. Why couldn’t they go to Inyathi Mission to learn road-making, mining and building? Moreover, Lobengula was perfidious and caused Rhodes a great deal of trouble. Rhodes himself was not a philanthropist but a self-confessed despot. Why should he educate the King’s children to be able to question his invasion of their father’s Kingdom?

In addition, Njube had attempted to return home without permission but was arrested in Bechuanaland and returned to the Colony where he died of a mental disease, and Nguboyenja had already died of a similar condition after returning home in the Kingdom from England where he had gone to study law but had on arrival been told Africans were not ready to study law and that he should study to become a veterinary surgeon instead.

He chose to return home to Matabeleland than remain in England to waste time studying something that had been chosen for him. He remained with his people for three months when his health improved considerably. He was, however, whisked away back to the colony where he died a few months later.

After his arrest in Bechuanaland, Njube became a recluse talking to himself but soon died of a similar condition as his sibling Nguboyenja. That closed the chapter on Lobengula’s children only 12 years after they were taken away from their own people to be “educated” by their father’s arch enemy.

Professor Ranger says had Nguboyenja been allowed to remain in England to complete his law degree he would have become the first African lawyer in the country 50 years before Herbert Chitepo.

Jonathan Maphenduka can be contacted on 0773 332 404

Comments