The two imperialisms: A lament

Perspective, Stephen Mpofu

THE colonisation of Africa in the 19th century was the first, or forerunner, of the two imperialisms, the other being hegemonic or contemporary imperialism now trying desperately to sneak into independent states and helped by power-hungry opposition political parties to worm their way into the hearts and minds of Africans.

In the first imperialist onslaught, European powers sought and scored a marked success in emasculating the African personality, shunting the whole complex of the attributes of black people, including their human rights, well beyond the shade and into limbo, even into oblivion in some cases.

The colonialists were helped by traditional chiefs in their project to tame the Africans into submission to colonial authority, the chiefs themselves being willing partners in seeking the submission of those living under their jurisdiction.

Of course, the white settlers dug in their heels after failure by their forerunners to weaken Africans by carting off, again with the help of chiefs, countless numbers of blacks, as though they were inanimate commodities for sale, to the West during the slave trade.

Once they had settled down, the colonisers plundered Africa’s rich natural resources, blued them away to build palatial edifices back in their native countries, while in the countries of their subjugation the white settlers named streets and schools after their own heroes in their native homelands so they would feel at home away from home.

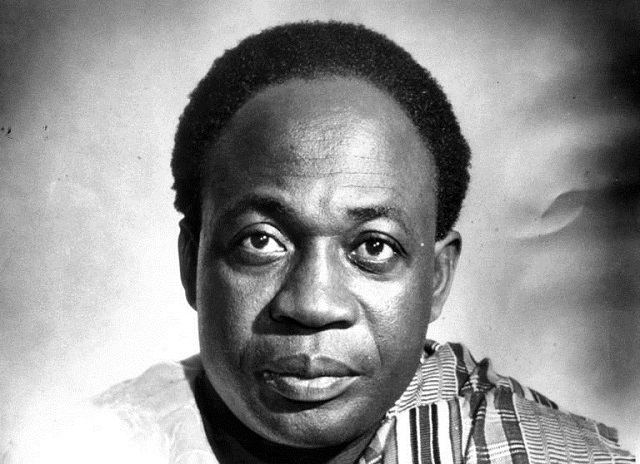

While this went on, African nationalism started to bud and although still nascent it gave off strong hints of invincibility which would clearly manifest itself in the 1950s and 1960s during imperial Britain’s prime minister Maurice Harrod Macmillan’s “winds of change” blowing across Africa with Ghana becoming the first African country to achieve independence under Kwame Nkrumah, followed by Nigeria and other countries also under British colonial rule in East Africa and those ruled by France in West Africa.

Those countries received freedom from their foreign rulers during the struggle for independence which eventually took on a revolutionary, armed liberation struggle dimension in imperial Britain’s colonies in Southern Africa, including Southern and Northern Rhodesia now Zimbabwe and Zambia respectively as well as in Portuguese East Africa, today’s Mozambique, as well as in Portuguese West Africa with Angola as Portugal’s most prominent possession in that region.

Inspired by the new freedom enjoyed by other countries, two and at most three political liberation parties in each of the countries still under colonial rule competed, as it were, with one another, not against each other, for the ouster of colonial governments that were racist and oppressive against indigenous populations.

Thus the enormous, combined pressure mounted on the foreign rulers finally paid handsome dividends of the freedom and independence for which countless numbers of young men and women paid with their lives.

In this regard Algeria’s revolutionary and socialist President Ahmed Ben Bela, in power from 1962-65 obviously, deserves kudos for the assistance that his country gave Zimbabweans in the armed revolution against the white, colonial Rhodesian rule for Algeria became an inspiration for freedom fighters still fighting the bush war to reclaim their land from intrusive, foreign rulers.

Now comes the tragic development that has negated, and continues to retard Africa’s political, social and economic emancipation to a higher plain.

It is a situation that calls for the mother of all laments as it demonstrates a lack of maturation in Africa’s political system.

The uhuru that came to so many countries after a protracted armed struggle has and continues to shift, like the sands of the Sahara, with political parties in independent states at each other’s throats to wrest power from fellow black rulers, and aided in this ironic twist of the hunger for power by former colonisers, or Western imperialists malevolently citing the need for “democracy” and/or the preservation of human rights.

In their own countries the contemporary imperialists boast at most two major political parties that take turns to rule with a third, smaller party, acting as a political catalyst. These hegemonic intruders promote as agents of “democracy” a multiplicity of opposition parties in each African state to promote the foreigner’s hidden agenda.

The political parties that the foreigners promote through financial support in turn become a bonanza for the recruitment of proxies or stooges or instruments for the ouster especially of governments formed by liberation movements to avenge their defeat by guerillas during the armed struggle as well as to consummate the second imperialism via hegemonic control and exploitation of Africa’s rich mineral and wildlife endowments.

Of course, when the opposition political parties act as Trojan horses by smuggling in foreign powers in hopes of being elevated to power themselves against their fellow black rulers, can one blame, and with justification, the foreigners using their political experiential superiority and impunity for wanting to run independent African states as though these were backyards of the imperialists?

The disunity of Africans politically should be seen as a prescription for their own downfall as nations, the indictment of the political system on the African continent which remains far, far from maturing.

Is it not a shame, and a sign of their small political mindedness when leaders of an opposition party that loses an election, as what happened next door in Zambia, say they want to “liberate the country” from a party of fellow blacks in power?

Similarly, opposition parties in Africa’s newest state, South Sudan, and those in our own country say they want to liberate the country from fellow blacks in power by ousting the incumbents.

The struggle to achieve that “liberation” objective results in losses of lives and limbs and of property — the kind of instability that reverses the clock of economic, political and social emancipation of the people.

Why do parties on either side of the political isle shy away, or are afraid of dialogical engagements for peaceful resolutions of their differences so that a purposeful unity overriding political differences will help engender progress in the development of the motherland, any motherland?

The altruism that “violence begets violence” is valid to the extent that those who seek to remove others from power by violent means will themselves be subjected to the same taste of fire should they accede to power by violent means.

The postures of saviour by imperialists should always make small, free countries wary of the intentions of Big Brothers and question any gesture proffered by the foreigners whether these pronouncements are made with tongues dipped in a sugar solution to sweeten them.

The Arab Spring of 2010-2012 in North Africa and in the larger Arab world in the Middle East, which left the countries affected perpetually distabilised, should make African countries guard themselves against self-anointed good Samaritan countries with track records that have never passed the litmus test of genuineness or honesty.

Even though Americans, who launched that project, have christened it “a democratic revolution”, there is absolutely nothing democratic about the instability and chaos resulting from that impunity.

Therefore Zimbabweans and those others in free, independent and sovereign African states should not behave foolishly, like children who touch a fire with their fingers to discover if it indeed burns and, if so, how much searing pain the burns cause.

Comments